The value of an investment today is the sum of all the cash flows that investment is going to generate over the life of that investment, discounted to the present at an appropriate discount rate. That applies to anything that is deemed an investment.

And then there is the Efficient Markets Hypothesis that states that all available information about an investment is reflected in the price of that investment at any given time. If and when new information about that investment becomes available, it gets instantaneously reflected into its price.

The fundamental assumption that underlies all these investment truisms is that investors are rational beings. That we as a collection of market participants would always make optimal decisions that benefit us in the long run. That self-interest, hence makes all these truisms plausible.

But plenty of evidence proves that we behave anything but rationally. We like belonging in herds because nature has made us make decisions more comfortably in herds. We find safety in numbers.

Any wonder then that we pile into the same investments at the same time and pay top dollar for them when that behavior is exactly the reason most investors underperform over time.

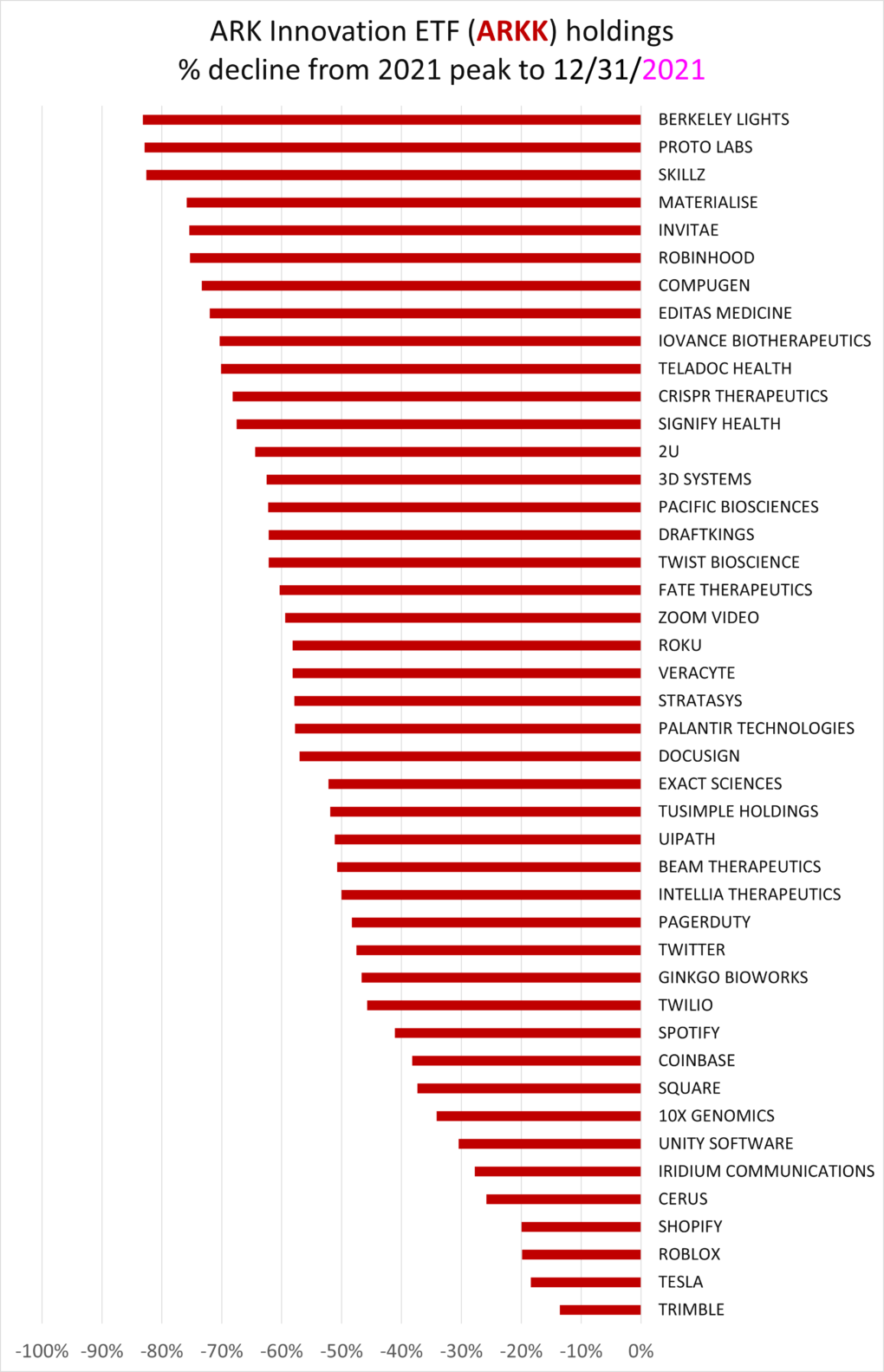

Case in point, the Ark Innovation Fund (ARKK). I wrote about this (Recency Bias) on how statistically unlikely it is for this fund or any other such fund to continue to perform the way it did, not because I somehow knew what was to come but because history proves over and over again that hot streaks, not rooted in fundamentals, are bound to end.

It ended for ARKK as well. That was expected for a fund designed to shoot the lights out.

But if you had an investment thesis going into the fund and if that thesis still holds, you should rejoice at such price declines because you get to buy the investment at a discount.

But what are the investors in the fund doing? Precisely the opposite. They piled into it at the peak, but many seem to be running for the hills ever since.

Any wonder then that there exists a persistent gap between what an investment earns versus what a typical investor investing in that same investment earns. Morningstar pegs that behavior gap at 1.7 percent annualized return that investors sacrifice by dashing in and out of investments at precisely the wrong time. That might not sound like much but try compounding that over say a 50-year a typical investor’s timeframe and we are talking real money.

And that gap persists because we do not think much about what we are buying and why we are buying it. We do not think how an investment fits into our plan. Or does it even belong in our plan?

And hence when the bad times come which they eventually do for all investments, we bail.

Personally, these kinds of fly-by-night investments (ARKK) don’t fancy me much because I don’t consider them as investments. But the absolute carnage in the prices of the fund’s holdings the last time I crunched the numbers is a sight to behold.

I checked the fund’s holdings again a mere two years later and it holds a completely different set of investments. That is not investing. That is Vegas-style speculating.

I would not want anyone speculating with my money and neither should you.

Cover image credit – Lilartsy, Pexels