Tariffs are bad. All sane economists know they are bad. Bad for the country that imposes them, bad for the country they are being imposed on, bad for global trade, they make the world poorer, they make the world less safe.

And it is not like they haven’t been tried before. Economists widely believe that the Smoot-Hawley tariff bill of 1930 was a contributing factor that caused the Great Depression. The tariffs enacted on imported goods at the time led to retaliatory tariffs from other countries. World trade declined by 65% over a span of five years and the rest as they say is history.

Politicians use tariffs to win back votes with a promise that they’ll bring back jobs lost to free trade. But why would a rich country like America want those kinds of jobs? Do we think that the Lululemons and the Nikes of the world will start making t-shirts and sneakers here? And if they ever do, are their customers willing to pay many times more for their products?

In an ideal world, we want freer trade and healthy competition between countries. We want a country that is good at making t-shirts to continue making them while the rich nations continue making products higher up in the value chain. Walmart making t-shirts in Bangladesh means cheaper prices for us while providing a source of income for the worker in that Bangladeshi factory who would otherwise starve. They can then feed, clothe, and educate their kids.

You say why is that our problem? It becomes our problem because unemployed people destabilize countries. They end up electing leaders who seek to exact revenge for their grievances on the wider world. There is evidence that say that the 1930 tariffs gave rise to Hitler, and we know how that turned out. The more we trade with other countries, the less chance of wars because there is too much to lose on both sides.

And imagine having to spend $100 on a t-shirt that should cost $20. That means we have less money to spend on other things. We eat out less, we buy less of other stuff, we have fewer disposable savings to invest in new businesses. Business activity then shrinks. Businesses curtail new investments, reduce hiring, and start laying off workers and the doom loop accelerates. Everyone suffers.

And tariffs impact the poor the most as a lot of their income is spent on meeting basic needs whose prices inadvertently rise due to tariffs. They reduce their spending but there is only so much they can cut.

Free trade on the other hand makes the world richer. When Bangladesh gets enough business from the rich world, their GDP rises. People there get rich and start buying iPhones and sneakers. Which means a growing market for companies like Apple and Nike to sell their products into.

Not all businesses like free trade. Imagine you are the buggy maker when automobiles didn’t exist. You’d want to protect your business at all costs to make sure your buggy-making business continues to thrive. And if the buggy-making industry had enough clout, they’d help elect politicians that will not allow an automobile factory to get built and we’ll all be poorer for it.

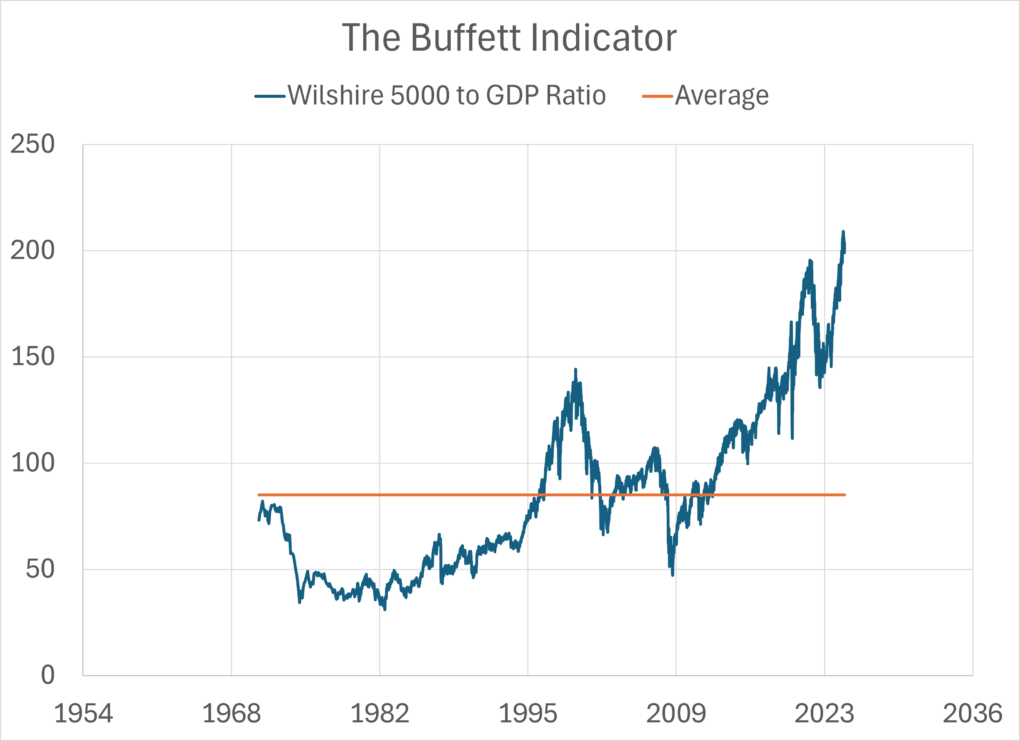

But businesses in general don’t like tariffs and we see it with how the stock market reacts to their impending enactment. And we know why. Tariffs cause input costs to rise so that is the first hit to profits. To top it off, people buy less stuff when a business raises prices for the product it sells to offset the increase in input costs.

So, business revenue declines and the cost rises which means less profits. And since business value is derived from future profits, its stock price declines.

But why the sudden drop in stock prices? Shouldn’t the markets have priced the impact of the tariffs over time? Good questions and the only thing we can conclude is that the market did not think it would really happen and to the extent it did happen and hence the resetting of expectations.

But calmer heads will prevail. Maybe it is a negotiating tactic, and the tariffs get scaled back.

The good thing is that the stock market is behaving exactly as it should. Stock investing is supposed to be risky. If there was no risk, the prices of stocks would rise to a point where no excess return exists over safe Treasury bonds. Price declines hence are healthy. The risk with owning stocks must show up from time to time to make investing rewarding over the long term.

What do you do as an investor? That is where your plan comes in. If you see gaps to fill in your plan and if you have cash to invest, it is time to invest. Who doesn’t like a discount on owning the world’s best businesses?

And once you have done everything that needs to be done, sit tight and go live your life. You own a 50-year plan so what happens from one year to the next hardly matters over that time span.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Julius Silver, Pexels