Up until the 1890s, horses and buggies ruled the land. There were incremental innovations within that ecosystem but nothing transformative. Then Henry Ford came along with the Model-T car and the buggies were history.

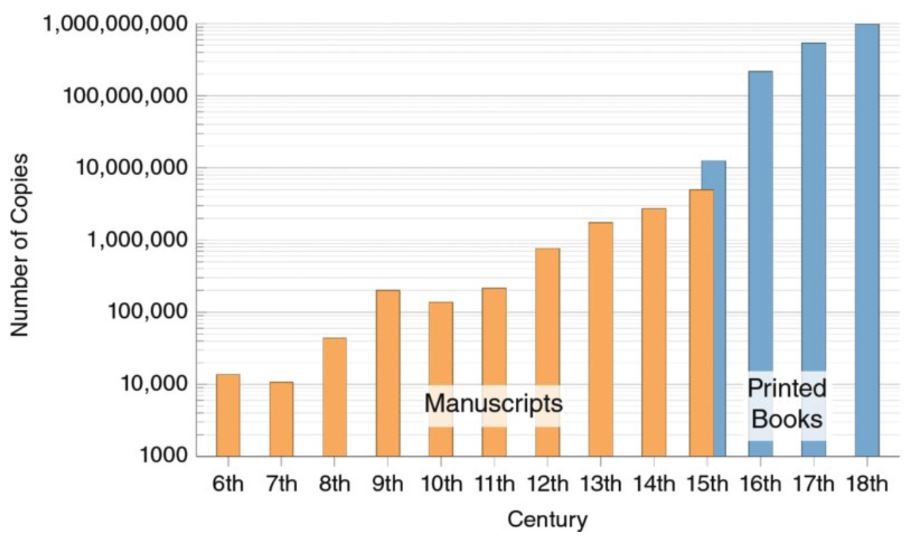

Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 1450s drove the manuscript writers out of business. I mean before that, you’d have armies of people literally writing pages by hand, one book at a time.

But once we could print stuff en masse…

Something similar transpired with the advent of electricity, the light bulb, the telephone, the internet and a million other big and small inventions that rendered the old way of doing things useless.

Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian-trained economist, called this the process of Creative Destruction. Capitalism and creative destruction go hand in hand. They kill the inefficient to reallocate resources to the efficient.

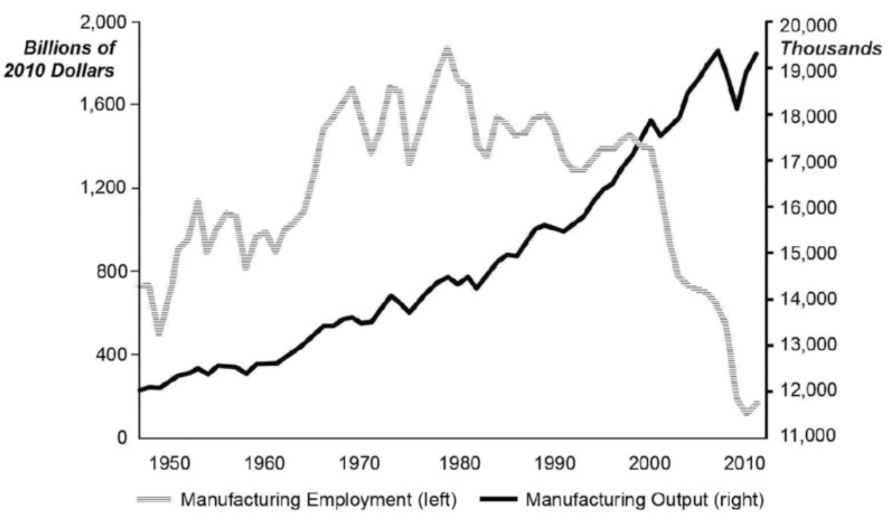

Take manufacturing for example. United Sates is a powerhouse in manufacturing, second only to China. And that with a mere ten percent of its workforce employed in that sector.

Less labor required to produce more stuff is a great thing for the economy but not so for the workers being impacted. There is hence a need for a strong safety net to catch these people when they fall but progress should not be allowed to stop.

Because all net wealth created in an economy is due to increases in productivity. And wherever capitalism’s forces of creative destruction remain unleashed, productivity growth follows.

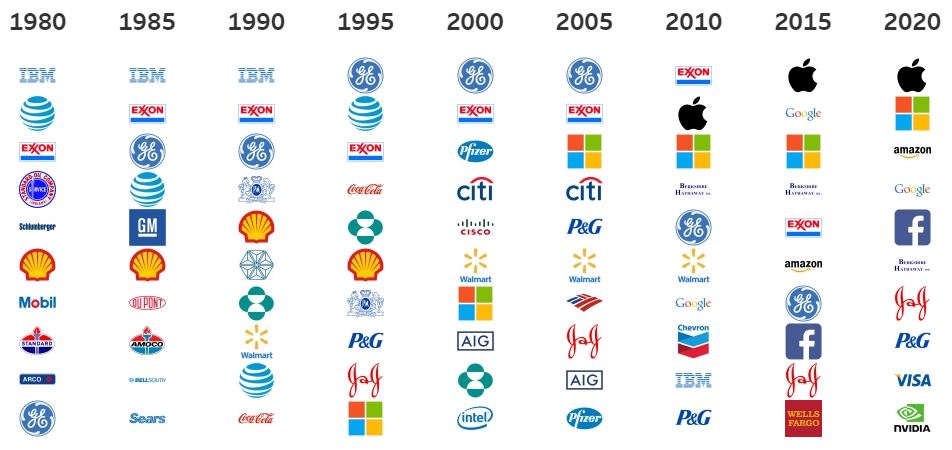

Image credit – Fewer, Richer, Greener: Prospects for Humanity in an Age of Abundance by Laurence B. Siegel

Business values rise, shareholders get rich, and everyone benefits when the economy produces more output with fewer inputs.

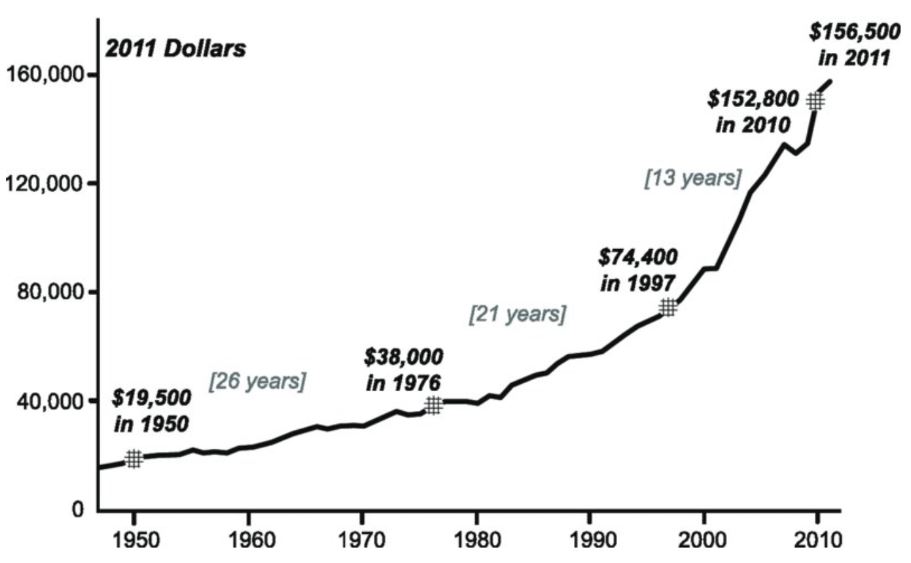

To comprehend how good we have it today, let me take you to the good old days of the early 1900s when John D. Rockefeller was the richest man around. Yet he had no TV, no internet, no air-conditioning, no airplane travel, no mobile phones and not even penicillin1. That was life for the world’s richest.

Or take Calvin Coolidge, President of the United States during the 1920s. His son died due to an infection caused by blisters that he developed while playing tennis. A President’s son dying from blisters, an implausible likelihood these days for literally anyone, anywhere1.

Or take Maria Theresa, head of the Habsburg empire in the 1700s, who saw six of her 16 children die before reaching adulthood2. Even the poorest regions of our planet have a higher survival rate today.

Life is so good, yet we feel inadequate because we compare and contrast, especially when it comes to money. And then we get sad. It is hard to find perspective but find we must. Each one of us is way richer than we think we are.

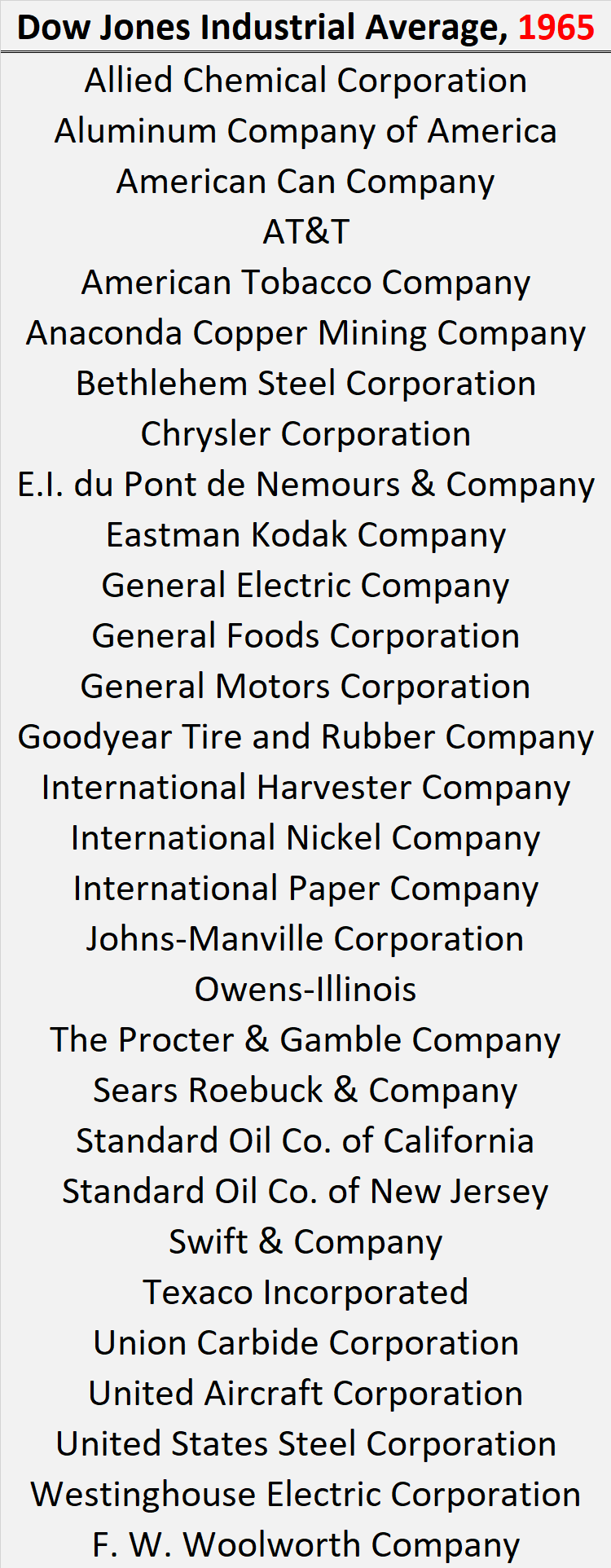

But back to capitalism’s forces of creative destruction, they are alive in our portfolios as well. And what better way to demonstrate that than to take a look back again to the 1960s world of stock portfolios where if you didn’t own Xerox, you were a loser. If you didn’t own GE, the General Electric, you didn’t know what you were doing. Same for IBM, Eastman Kodak, Polaroid and on.

We know about the Dow Jones Industrial Average, an oft-quoted stock market benchmark that is supposed to measure how our economy is doing. Stock markets are not everything, but they have become everything and that is a good thing.

So, imagine you are in 1965 trying to build a portfolio to invest your savings into and you’d of course be looking for the bluest of the blue chips. And what better way to populate your portfolio with than to just buy what the Dow owns.

And these were the companies it owned…

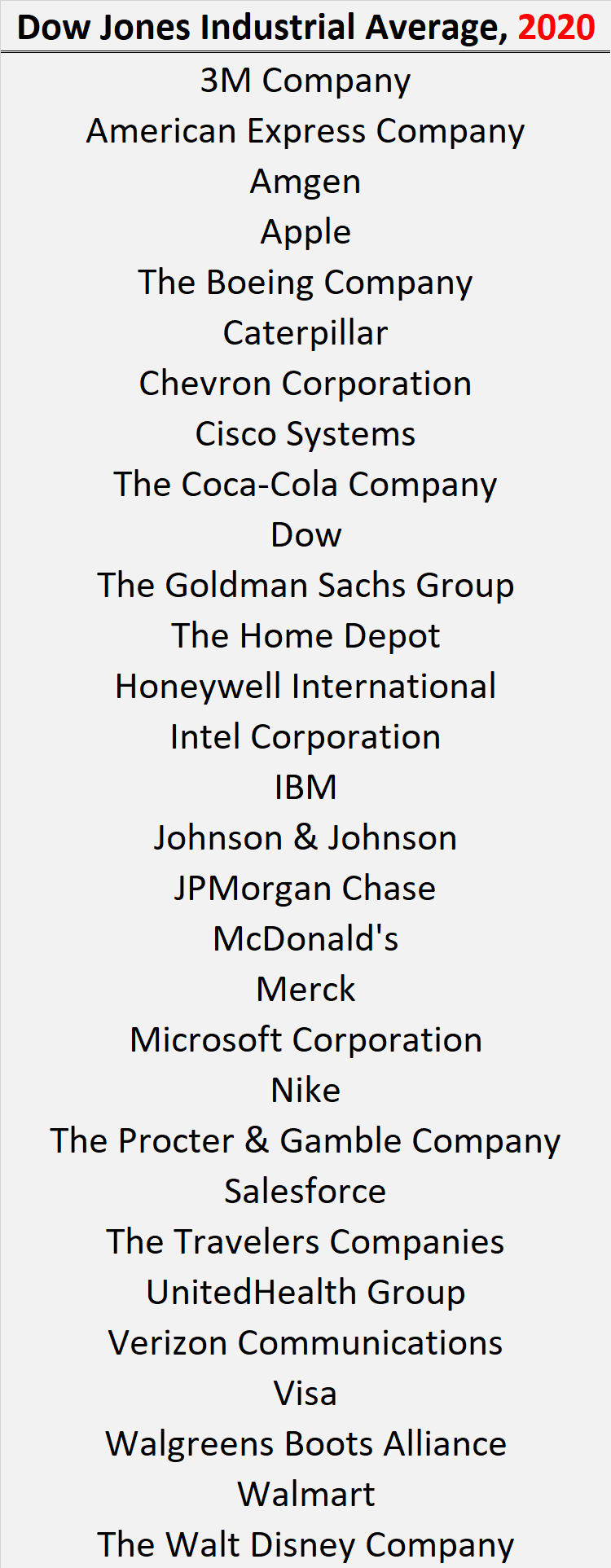

But then Schumpeter‘s forces of creative destruction kicked in, and this is what that same Dow owns today.

So, if you held onto the businesses of 1965 beyond their useful life and made no changes, you could be hurting. I don’t know for sure as it is hard to crunch the numbers as businesses get merged or get spun off or go extinct.

But what I do know is that a single $10,000 invested in 1965 would be $2.5 million today even in this relatively dumb way to build portfolios and that is by owning just the Dow. And that is because the Dow kept on evolving as the economy evolved.

John VanGavree, a U.S. State Department analyst put together a dashboard that highlights the changes in the top 10 holdings in the S&P 500 index in five-year increments. Even in such a short period of time, the index components change and sometimes by a lot.

This mostly happens because large companies become slow and bureaucratic, and difficult to navigate for employees who want to break things.

So, they leave, picking up venture capital on their way out and starting new disruptive businesses.

So too top-heavy a portfolio adds this extra layer of large-company disruption risk that should be designed around.

Plus, data going back to 1970 show that companies that finished in the world’s top 10 in terms of market value had less than one in five chances of finishing the next decade there.

And in the decade after companies reach the top 10, they typically see earnings growth fall and profitability decline. Investment performance of course always follows so they end up giving back all the excess gains they made in their run up to the top3.

Competition and churn lie at the heart of a functioning capitalist system. That is why the giants of one decade so often deliver such underwhelming returns in the next one, and shrink in the popular imagination. Expect that pattern to recur unless capitalism is truly broken.

“How the US tech giants could fall” by Ruchir Sharma, Financial Times, August 15, 2021

And competition is always there, waiting to gobble up any edge a business has, and disruption happens these days at a pace never seen before. There is no way to tell if the stock of a business you own today which is at the top will stay there a year from now, forget a decade.

So, some takeaways…

- The darlings of today may appear invincible. They always do. But unless capitalism is truly broken, they will be replaced. They must be. So, if your portfolio is overly concentrated with these darlings, you must plan to un-concentrate before it is too late.

- And the fact they are the darlings today means everyone knows about them. And when everyone knows about them, everyone wants to own a piece of them. So, more demand with the same supply of shares means price inflation. And you pay for that by paying inflated prices. Yes, markets are supposed to be efficient, but they seldom are in the short term.

- You might be unknowingly concentrated in some of the top names with no fault of your own. Maybe you work for one of these businesses and you acquired shares through employee plans over time. As much as you hate letting some of your shares go, let go you must because history is not on your side. The way to do it is to build a plan that errs on the side of conservatism and use that plan as a guide to trickle out of your shares. Let the plan dictate what you should do mechanistically instead of using emotions to guide your decisions.

- And last, design a portfolio where you get to participate in the rise in the value of a business from small to mid and from mid to large. That is an extra value capture that you can extract through portfolio tilts towards different segments of the market. Some will complete the full cycle from small to mid and from mid to large and eventually to extinction. Others may get acquired halfway through that process and some may flame out prematurely. But owning a broad enough basket of them, spread across the size spectrum means you’ll get to own a turbo-charged version of all that capitalism has to offer.

Thank you for your time.

1 David Henderson. “Richer than Rockefeller“, Econlib. February 8, 2018.

2 Laura Vanderkam. “All the money in the world“.

3 Ruchir Sharma. “How the US tech giants could fall“, Financial Times. August 15, 2021.

Cover image credit – Smithsonian Institution