We’ll start with the simplest of all possible investments and that is buying Treasury bonds. When we buy a bond, we become a lender. And with Treasury bonds, we become a lender to the U.S. government.

So, say the yield (interest rate) on a Treasury bond that matures in 10 years is 5 percent. For every $1,000 invested in that bond hence, the U.S. government pays you $50 each year as interest payment. And they do that for 10 straight years. That is the U.S. government compensating you for borrowing from you.

When that bond matures (when the loan term ends in 10 years), you get your original principal amount ($1,000) back along with the final year’s interest.

Treasury bonds are the safest of all investments so your chances of losing money investing in them are virtually nil.

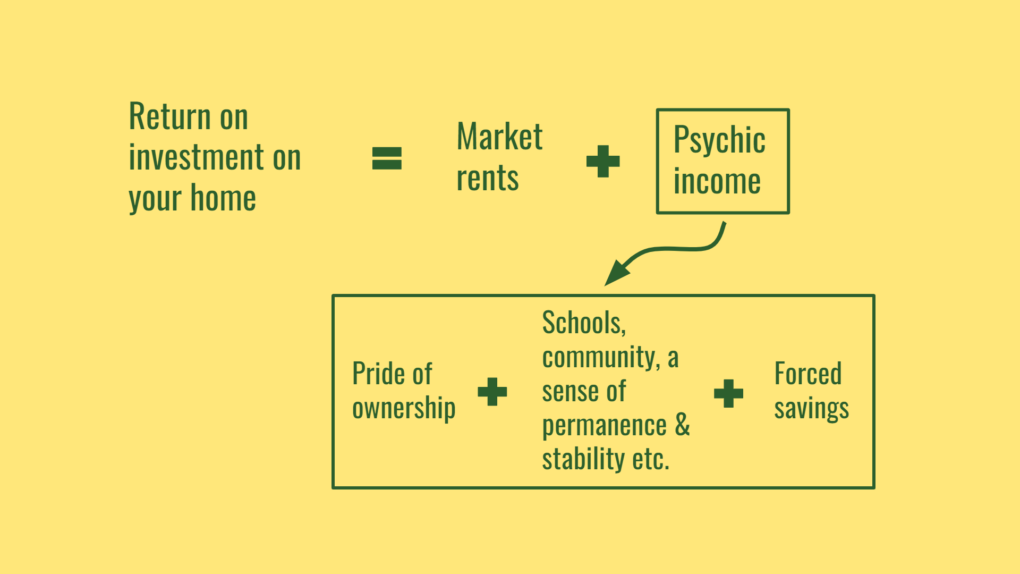

With that as a backdrop, we now turn to the most widely held of all investments, an investment you can touch and feel and live in and that is, your home. Estimating return on that investment gets a bit murky but fundamentally, it is the market rent on that home. If your all-in costs are higher than what you can make if you were to rent your home out, you are losing money on that investment.

But your home is not just an investment. It is your home. You derive a surplus psychic income from owning it. Schools, community, some aspect of forced savings, a sense of permanence and stability, pride of ownership – these are all pieces of that psychic income.

It is hard to put a price tag on that surplus psychic income but that plus market rent is the return on investment on your home. If home prices rise, the market rents on those homes must rise as well. There will be lags but those lags eventually heal. If they won’t, you’ll be losing more money owning a home.

Where it is more black and white is with owning rental real estate. Your return on that investment is the rent you collect minus your expenses. There is no psychic income there. The market decides the rent you can charge and that minus expenses becomes your return on investment in any given year.

We now turn to investing in businesses. Businesses create wealth so you’d want to own a piece of the machine that creates that wealth. Without businesses, there is no economy. Businesses in aggregate must do well for all other pieces in the investment ecosphere (bonds and real estate) to do well. Businesses sit at the top of our economic value chain.

You can run your own business but that requires super-human abilities. Lucky for us though, the stock market offers us a chance to own world-dominating businesses with a click of a button. You won’t ever have to get into the weeds of running them, ever. The superhumans hired to run these businesses on your behalf do all the heavy lifting.

So, say you own a piece of a business that trades at a price to earnings (PE) ratio of 20. Earnings is another word for profits. So, the market is pricing each dollar that a business earns in a given year at 20 times that. The earnings yield hence on that business is $1/$20 = 0.05 or 5 percent.

That is your first-cut return on investment as an owner of that business. And you being an owner (shareholder) have claims on those profits.

But then those superhumans running these businesses on your behalf decide that they have a better use for some or all of those profits. They want to expand into new lines of businesses. They want to grow the existing lines of businesses. They want to do all of that and more to make even more profits.

And as a profit-maximizing owner, that is what you’d want. Only the piece of profit a business cannot justifiably invest should flow to you.

And dividends, which are cash payments into your brokerage accounts, is one way that profit gets returned to you.

Many businesses don’t pay cash dividends and instead, decide to do share buybacks with their surplus profits. Buying back and then retiring those shares increases your ownership stake in a business so they are an indirect form of dividend payment. You won’t see the cash coming into your accounts, but you should see the share price of the business you own rise over time.

And many businesses like the Warren Buffett run Berkshire Hathaway exclusively prefer doing share buybacks with their gushing of surplus profits instead of paying cash dividends. Why? Because cash dividends into your accounts mean direct income to you whether you want it or not. And income coming into your accounts means paying taxes on that income.

But with share buybacks, there is no direct payment to you. You decide when you want to take dividends by selling the appreciated shares. Share buybacks, hence, if done right by the businesses you own, are more flexible (to you) tax-wise than being forced into accepting cash dividends.

Many businesses in the hyper-growth phase do not do either because they, in theory, should have a much better use of profits than to give them back as dividends. They need all that capital and more to expand and grow.

But not every business deploys capital as efficiently as initially planned because projects sometimes fail. That is the nature of the game but if you own a bunch of them, more will succeed than fail.

But every business will eventually pay out the accrued profits back to its owners (shareholders) in the form of dividends. Those that ever won’t, fizzle out. Apple for a long time, did not pay a dividend. Now they are a dividend stalwart. And they do billions of dollars’ worth of share buybacks each year so even more indirect dividends.

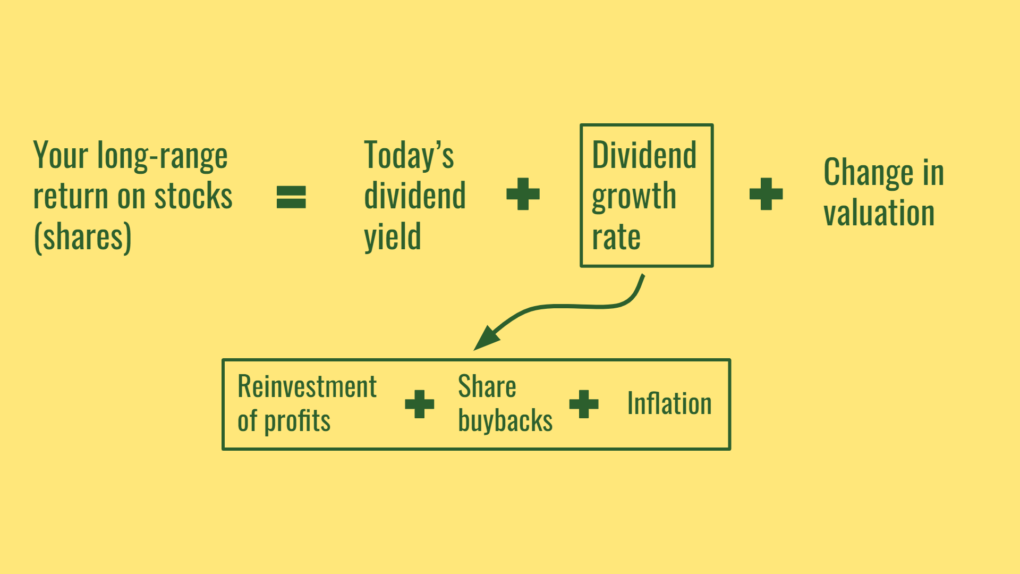

There is another big driver to your long-range returns with stocks and that is changes in valuation. That is what John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, calls the speculative aspect of your total return. Speculative because it has nothing to do with the goings in a business and everything to do with what investors will pay for each dollar of earnings that business earns today versus in the future.

So that business we alluded to that trades at a price to earnings ratio of 20 today, say ten years from now, the market bids up its price to earnings ratio to 30. That is a big deal because that change in what investors are willing to pay for that same dollar of earnings adds an extra 4 percent each year to your total return.

But now your earnings yield as an owner of that business that started off at 5% when the PE ratio was 20 dropped to 3.33% at the new PE ratio of 30. Any new shares you buy from now on are not as great of a deal because your investment dollars are buying less business profits than before.

So, if you are retired and living off your portfolio, upward changes in valuation is great. But if you are still working and contributing to your investment plan, it is not quite a disaster but close.

What you want is downward changes in valuation in your accumulation years and not upward changes so that you continue buying a bigger and bigger slice of business profits with each contribution you make.

But no one likes that because most don’t know how this game works, but we do.

To summarize…

Dividend yield on global stocks is roughly 2% today1. Add in dividend growth rate of 5 to 12% in any given year and that is your baseline expected return from stocks. Tag along changes in valuation and you get the total return. Anything more means uncompensated risk. No problem doing it with a tiny slice of your savings but overdoing it could eventually kill.

And anything that is deemed an investment must have associated cash flows. With bonds, we have interest income. With real estate, we’ve got rents. And with stocks, we have dividends.

Anything that does not generate cash flows is not an investment. Gold is not an investment. Commodities are not investments. Currencies are not investments. Crypto is a scam.

So, having a rough idea about where the return on your investment comes from and how much of it should you reasonably expect is critical to preventing you from getting bamboozled out of your hard-earned savings.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Marlene Leppanen, Pexels

1 December 31, 2022