Cockroaches are the ultimate survivors1. They can live without air for an hour, without food and water for months. They can survive the Arctic cold. Ice ages and continent shifts mean nothing to them. It is no surprise then that the cockroach as a species has been around for 300 million years and it is not going anywhere soon.

Your plan should have the same survivalist foundations as that of a cockroach. No matter what the world throws at it, your plan must survive.

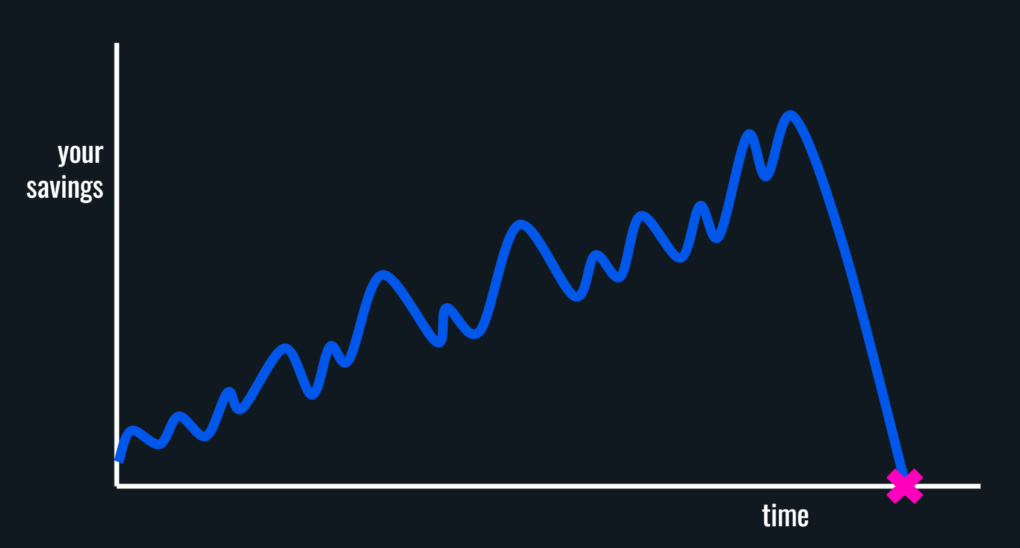

So never set yourself up for a disaster like this…

And disasters like these happen all the time. Leverage, which is when you borrow money to invest, is oftentimes to blame.

Tying up a big chunk of your net worth in one or two stocks is another very common cause. That is taking on unsystematic risk at its core and the outcomes could be life-altering…

Former Enron Corp. employee George Maddox, who lost his retirement savings when the energy giant collapsed, says he has been forced to spend his golden years making ends meet by mowing pastures and living in a run-down East Texas farmhouse. Maddox, who served 30 years as a plant manager with the company, was long retired as Enron began spiraling out of control in the months leading up to its bankruptcy on Dec. 2, 2001. With all his retirement savings tied up in 14,000 shares of company stock, then worth more than $1.3 million, Maddox says he never saw the crash coming.

10 YEARS LATER: What Happened To The Former Employees Of Enron? Business Insider, December 1, 2011

I know of someone who went from $4 million in their employer stock to zero in six months. If you have seen some of the headlines around recent bank failures, you’ll know which one did it. That is literally all the money they had so life-altering is the least bad way I can describe it.

Unsystematic risk, in plain English, means you cannot predict the good (or the bad) about a stock for long into the future. You can do that with a basket of stocks (businesses) but with one or two stocks, in this day and age of hyper-rapid disruptions, it is a near impossibility.

And most of the concentrated stock risk unknowingly creeps up on you if you get paid in employer stock. You must then diversify out of it because for every story that pans out, there are multitudes more that fizzle away.

And when your employer’s story fizzles away, you lose the money that you invested in that stock, you lose your paycheck, your health insurance and the rest.

And regardless of how much you believe in the business you work for, it won’t be around forever. Things change, key employees leave, and competition is always waiting at the heels to eat into whatever moat your business currently enjoys.

And drawdowns (declines) are deeper with concentrated portfolios with no guarantee of a recovery. That reversion to the mean (more on this later) that is ingrained in the design of most broad-based portfolios could never happen to you.

Talk about drawdowns, you know that had you invested in Apple stock 20 years ago, you’d now be rich. But go back another 20 years and say you bought $10,000 worth of Apple stock in April of 1983, guess how much money you’d have 20 years later?

$8,400.

Are you telling the world that you would have the fortitude to hold on to a “loser” for 20 long years while the rest of the world gets rich? Not a chance.

Plus imagine the lifelong guilt and literal trauma you’d be living with had you waited for 20 long years only to eventually bail on that “loser” and then watch it soar to become the most valuable business in the world.

So do individual stocks ultra-sparingly and if you do decide to do it, do it with a tiny portion (under 5%) of your money with the intent of holding forever. If those stocks go nowhere, no big deal. You still have the bulk of your savings intact to take you to your goals.

And when I say do individual stocks, do it with stocks that can matter. Because you are looking for that lottery-type outcome to get compensated for taking on lottery-type risk.

So, you can’t be holding a trillion-dollar stock because for that stock to double, it needs to become a 2-trillion-dollar stock. How many 2-trillion-dollar stocks do you see around?

Plus, you likely own that trillion-dollar stock by the boatload anyway if you own a half-decent portfolio so if it were me, I’d own small, obscure stocks that have a shot, regardless of how faint, to do 10 times your money in 10 years.

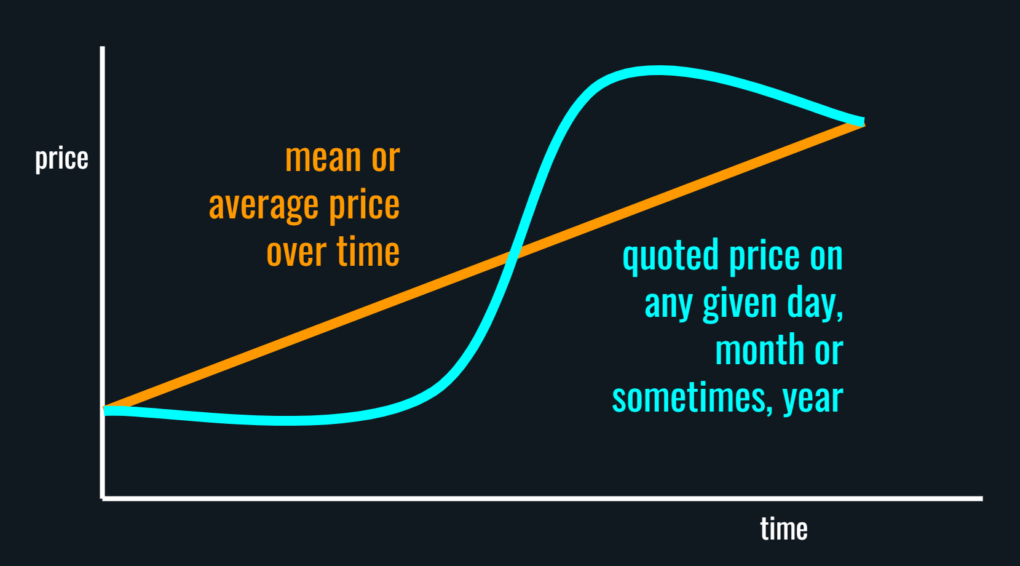

Reversion to the mean…

I passingly mentioned reversion to the mean but I feel it needs more explaining. Reversion to the mean assumes that the value of an investment, even if it were to decline, will eventually revert to its long-term trajectory of perpetual growth.

You cannot assume that with individual stocks because stocks go down all the time, never to recover.

But with a diversified basket of stocks that are at the top of our ever-evolving economic value chain, with that basket getting refreshed with new businesses as the economy changes, sort of like auto self-cleansing, the price of that basket can go down, but it will eventually recover. It must recover unless we are talking the end of the world kind of scenario.

This reversion to the mean backdrop is what then allows you to confidently dollar cost average into your plan, knowing full well that in the long run, the collective prices of the investments you own will recover. They must recover.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Erik Karits, Pexels

1 Loren Grush. “The Verge review of animals: the cockroach“, The Verge. January 17, 2016.