Treasury bonds are issued by the federal government. Bonds with a maturity of one year or less are called Treasury bills but we’ll keep calling them bonds.

So, say the year is 1999 when one-year Treasury bonds paid 4 percent as interest. If bonds with a maturity of one year paid 4 percent, you would naturally expect more payment from a five-year Treasury bond. Five years is a long time to wait to get your money back.

The five-year bond hence must pay like 6 percent else why would you take the risk of locking up your money.

And if the five-year Treasury bond pays 6 percent, same maturity corporate bond must pay higher. Corporations cannot print money, but governments can. Corporations carry that extra risk of going bankrupt.

Following along that risk spectrum, we would demand an even higher interest rate from an issuer of the same maturity junk bond, also called a high-yield bond. This is the investment world’s attempt at putting lipstick on a pig but do not be fooled by the pleasant sounding high-yield term. Junk bonds are issued by businesses that are on the verge of going out of business.

The riskier the issuer of a bond hence and/or the longer the time to maturity of that bond, the higher the rate of return. That is expected and that is how it usually goes. That describes the universe of bonds.

And if bonds yield whatever they yield, publicly traded stocks must yield more. Stocks are riskier than bonds because cash flows (dividends) from stocks are not guaranteed. And in the event of a bankruptcy, stockholders come last in line on any claims on business assets. So, stocks in theory should earn more than bonds.

If public stocks yield whatever they yield, venture investments must yield even more. We have to discount cash flows from venture-backed investments at a much higher discount rate than those for established, publicly traded businesses. That is a roundabout way of saying that we should expect a higher rate of return from venture investments than other types of investments because they are the riskiest.

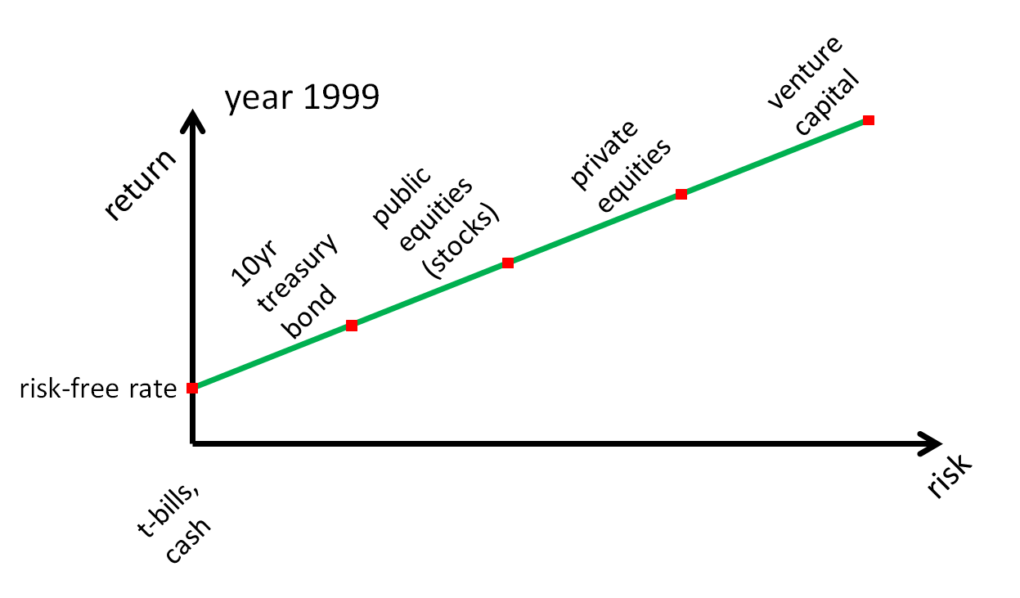

The risk-return relationship just described is the Capital Markets Line and it looks something like this…

Treasury bills (risk-free rate) are the shortest maturity and the safest of all investments. Venture capital is the longest maturity and the riskiest of all investments.

And we’ve probably heard that the more risk we take, the more return we’ll earn.

But if riskier investments could be counted upon to deliver higher returns, by definition, they wouldn’t be any riskier. The prices of those investments would be bid up to a point where no net return above the risk-free rate exists. So, the higher risk equals higher return theory does not quite hold.

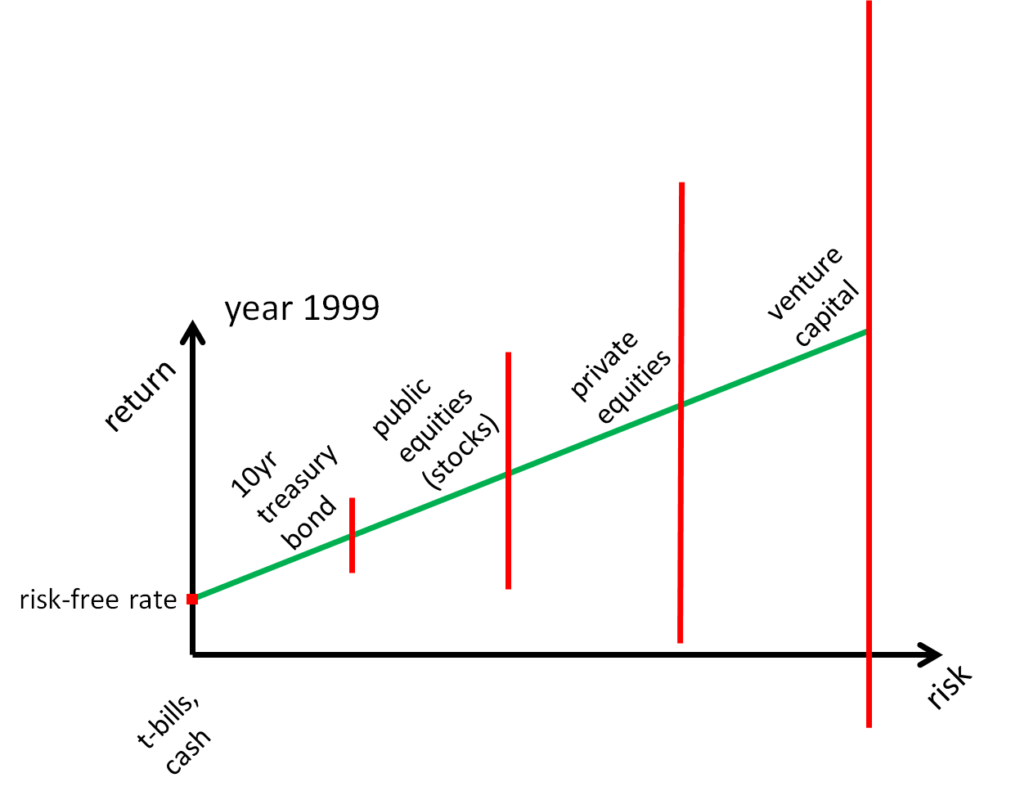

The correct way to formulate the Capital Markets Line then is…

We now have a distribution of returns instead of point estimates. The riskier an investment, the wider the distribution of return outcomes.

Howard Marks in his book, The Most Important Thing talks a great deal about this and more but this one quote captures the essence of the reconstituted Capital Markets Line…

The correct formulation is that in order to attract capital, riskier investments have to offer the prospect of higher returns, or higher promised returns, or higher expected returns. But there’s absolutely nothing to say those higher prospective returns have to materialize.

Howard Marks

Prospect, promised, expected mean the same. Investments that are riskier must appear to offer higher returns. They don’t necessarily have to deliver on that promise though.

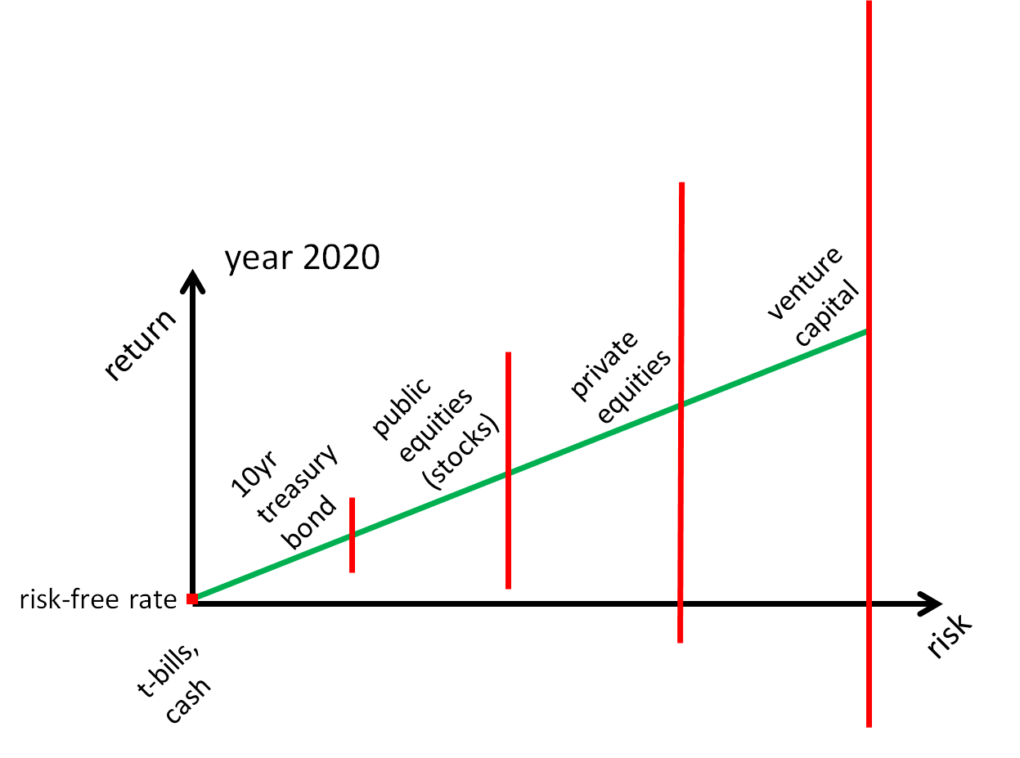

So that was the world of 1999.

Then we had some interim booms and busts so the Federal Reserve, in their attempt to make sure the economy doesn’t collapse, floored the interest rates.

The updated Capital Markets Line following that…

The entire line shifted down, which means the discount rates (expected rates of return) for each one of those investments moved down as well.

And when discount rates go down, investment values go up. The 4 percent bond you own now is more valuable when market interest rates are zero.

But when market interest rates rise again, we start to go back to the 1999 interest rate regime which then means discount rates rise and consequently, investment values fall. Projects and businesses that were flourishing in the low interest rate world suddenly don’t pencil out. Because the hurdle rate now is no longer zero.

But then your future expected return on any new money you deploy is higher. The time to invest is when investment values are low and expected returns are high. That is counter to how we behave but that is human nature doing what it always does.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Cottonbro, Pexels