You want to feel inflation? Try visiting a country like India every other year. I mean you are gone a while, but you only remember the prices of the past. Then you go there again and get price shocked everywhere you turn.

Inflation, an ever-present tax on us, is structural in most emerging economies. They import more than they export, which creates a deficit. But that deficit seldom gets plugged. So, they print more currency to replace the currency that left the country which then dilutes the value of that currency in relation to others. The stuff you import now costs more in your local currency, which is the definition of inflation.

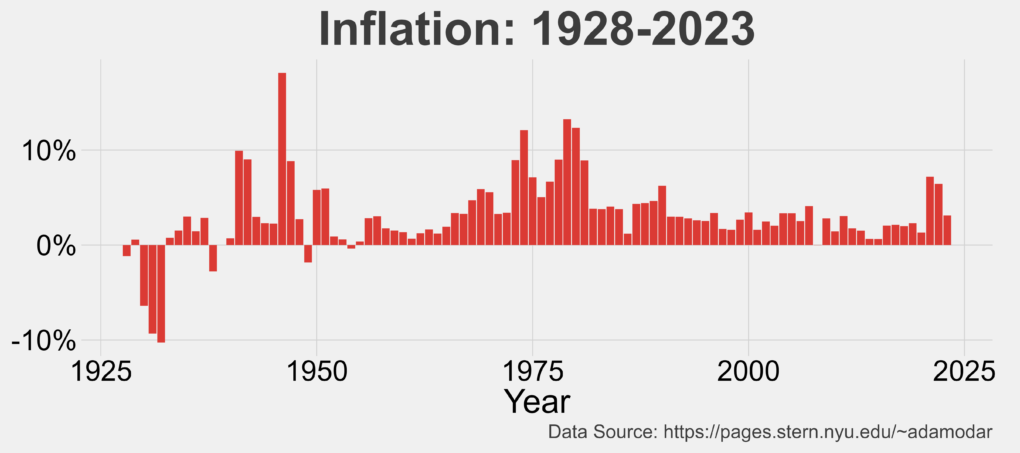

But then Covid happened, governments panicked and pumped a lot of money into the system while factories remained shut and we got to feel inflation firsthand in a supposedly efficient economy like that of the United States.

Some amount of inflation in an economy is by design but a big amount is unwarranted. And when it flares, it is hard to put a lid on it without causing pain. The last time United States experienced a major bout of inflation was in the 1970s but not many are around to remember it. But it took an economy-wide pain (double-digit interest rates and ensuing high unemployment) to bring it back down.

Inflation as always is too much money chasing too little goods. Either we reduce the supply of money, which means raising the cost of money, which means raising interest rates, which in turn reduces demand. Or we produce more goods.

But if producing more goods were as easy, we wouldn’t be in such a mess. Take housing for example, a big component of inflation that feeds into the data the Bureau of Labor Statistics collects. There are not enough homes to go around, we all know that.

Yet, it is not like we can flip a switch and make shelter abundant. It takes time but, in the meanwhile, raising interest rates is the only weapon used to temper demand for shelter.

Raise interest rates so it costs more to buy a home, so folks instead rent. But then rents shoot up so folks who’d be loving living alone are forced to double up. That new college grad of yours, ready to go out in the world, will be stuck at home a tad bit longer. Demand for shelter hence falls and with it, a big chunk of inflation.

Raising interest rates also raises the hurdle rate for businesses. Projects that were feasible when interest rates were low suddenly don’t pencil out. Projects get cut, jobs get lost. And without a job, you will not be buying as much stuff which reduces demand for that stuff which then lowers inflation.

Inflation is what author and investment advisor William Bernstein calls one of the deep risks to our financial plans. It is not volatility; it is not temporary declines in asset values that you should fear. Those are what he calls shallow risks. It is the long-term loss in purchasing power that you should fear much, much more.

Inflation most affects cash, bonds, and other fixed income investments so exposure to them beyond what is reasonable for your situation is going to cost you. Instead, you need a big chunk of your portfolio working to fight inflation. And stocks have historically proven to be the asset class of choice at doing just that.

And why not? Stocks represent ownership stakes in real businesses and businesses don’t just sit around and eat up the rising costs of their input. They will pass down those cost increases to you and me through price increases for the stuff they sell. Not all businesses will be able to do so. Those that cannot wither away and get replaced by the ones that can.

But adjusting to rising prices takes time so in the short run, there will be pain, even for stocks.

With bonds, you become a lender to a business. Even if that business were to go on to become the next Microsoft, your share of the profits is capped at the interest rates negotiated when you bought those bonds.

But in the event of bankruptcy, payments to bondholders come first before the stockholders get anything. Plus, interest income from bonds is much more predictable than profits from stocks. So, investing in bonds is supposed to be safer than investing in stocks and it shows up in the data.

Treasury bonds have longer maturities than treasury bills but, in both cases, when you buy them, you are lending money to the United States government. With treasury bonds, you are lending money for seven to ten years and treasury bills have maturities of less than a year.

Treasury bills or bonds can be used as a proxy for lending money to rock-solid businesses, but businesses carry a non-zero default risk so to get compensated for that extra risk, you will expect to earn more by lending money to businesses than to governments.

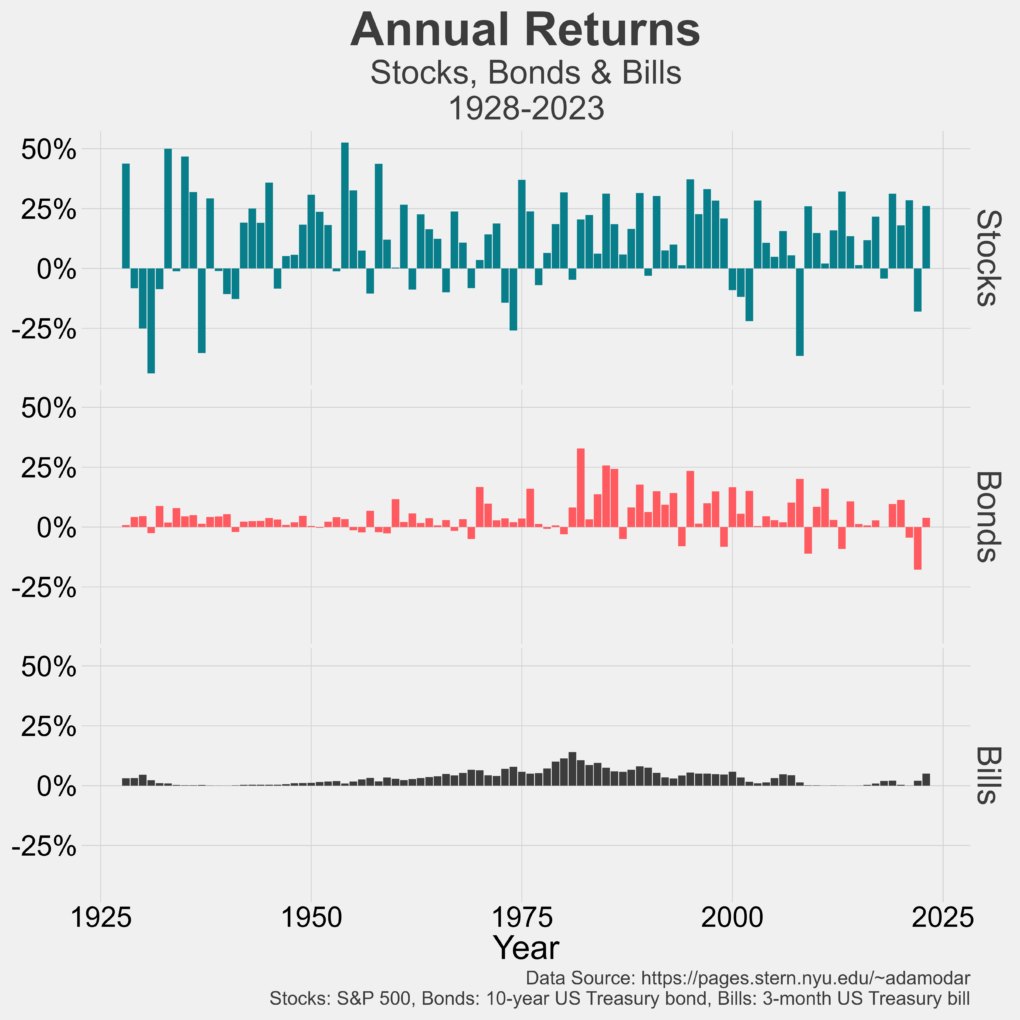

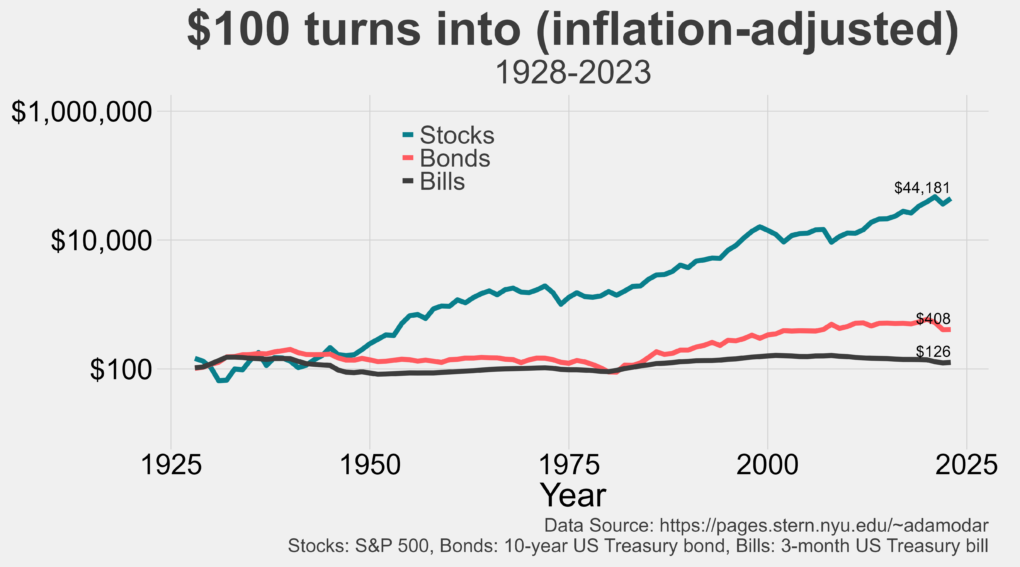

The apparent safety of bonds and bills over stocks is clear from the data above. The value of stocks sometimes gets cut in half. Bonds have had some negative years but not as many and their values don’t decline by as much as for stocks. Bills have been the safest with no declines at all.

But there is an enormous cost you’ll pay for the perceived safety of bonds and bills over stocks.

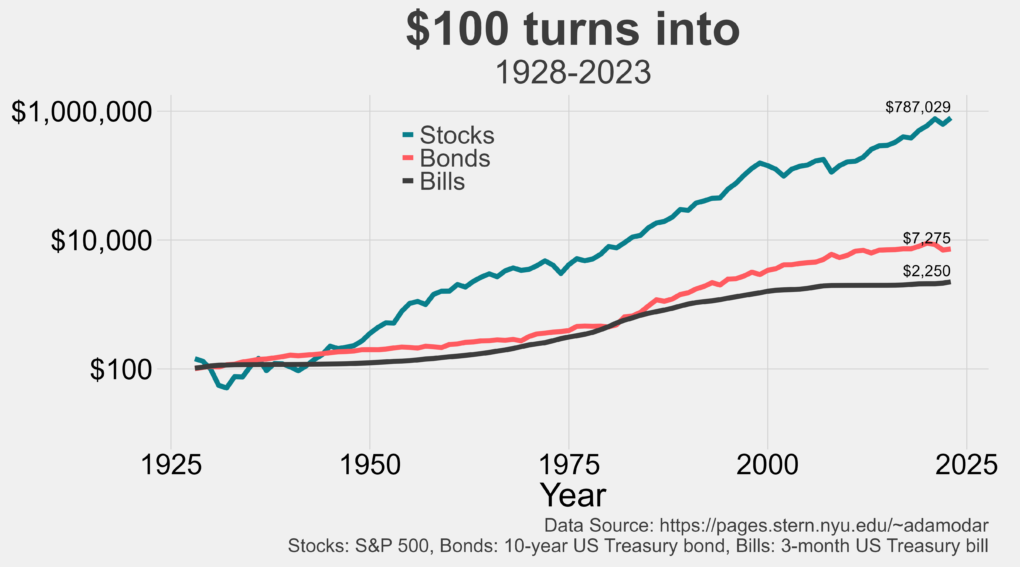

Granted, not many have 100-year timeframes to invest but maybe you do if you intend to invest with the next-gen in mind. The difference in outcomes though is as stark as it gets.

And log scales (in the plot above) tend to surreptitiously hide pain so do not be fooled by the apparently ‘small’ declines you see in the dollar amounts with stocks. Those declines are huge, but you must learn to live through them to deserve that favorable outcome.

And stocks must return more than bonds and bills because stocks represent business ownership while bonds and bills in a way represent the cost of financing those businesses. Businesses won’t exist if over time, they don’t earn more than the underlying cost of financing them so stocks outperforming bonds and bills makes sense.

But if you think bonds and bills are safer than stocks, let me introduce you to their arch-nemesis, inflation.

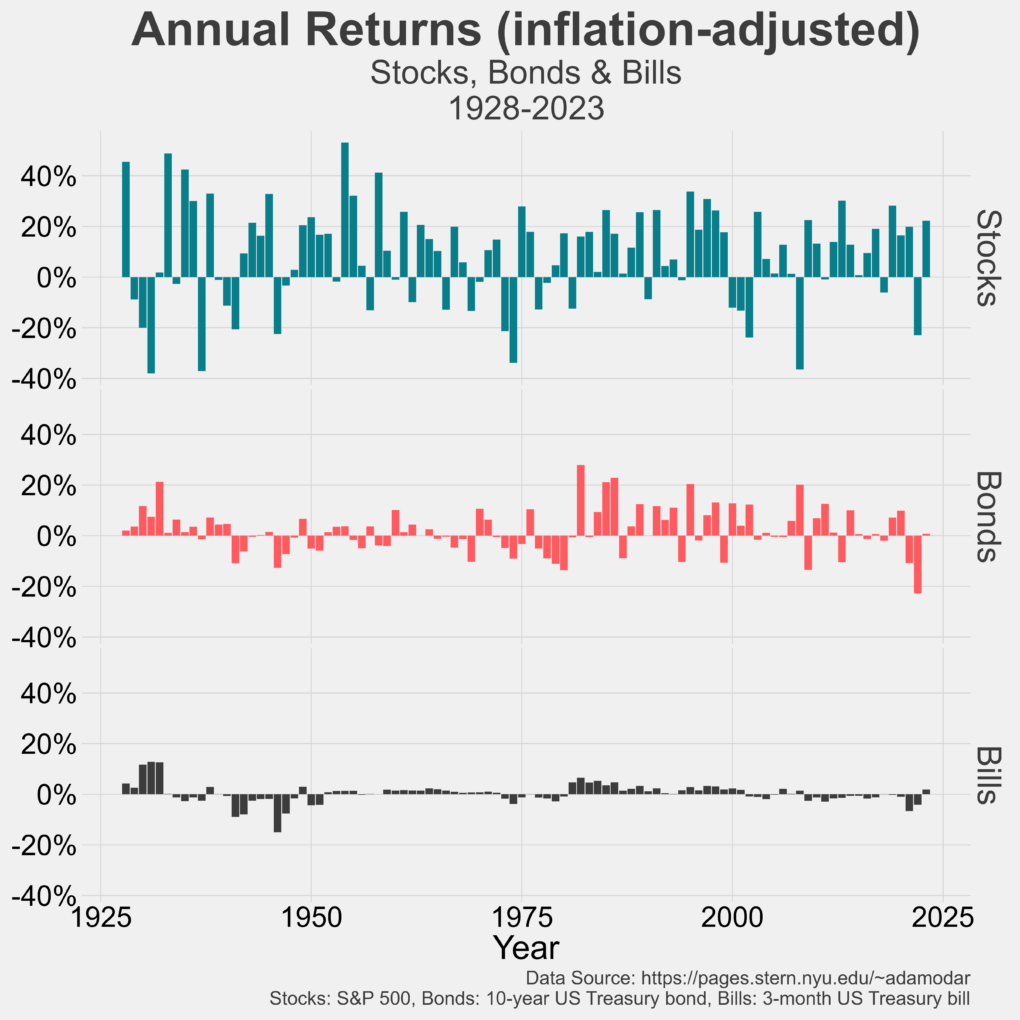

Inflation-adjusted return is what counts because that is the real growth in wealth.

The returns of bonds and bills no longer appear as safe once inflation is taken into account. And that is how it should be. You can’t be rewarded for sitting on cash. There is no free lunch in investing.

So, in inflation-adjusted terms, your purchasing power with treasury bills stayed flat, was up 4x with bonds and 440x with stocks. Stocks did win.

That win of course didn’t come free. You’d have to wait, sometimes for years, to experience the magic of compound returns but wait you must.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Pixabay