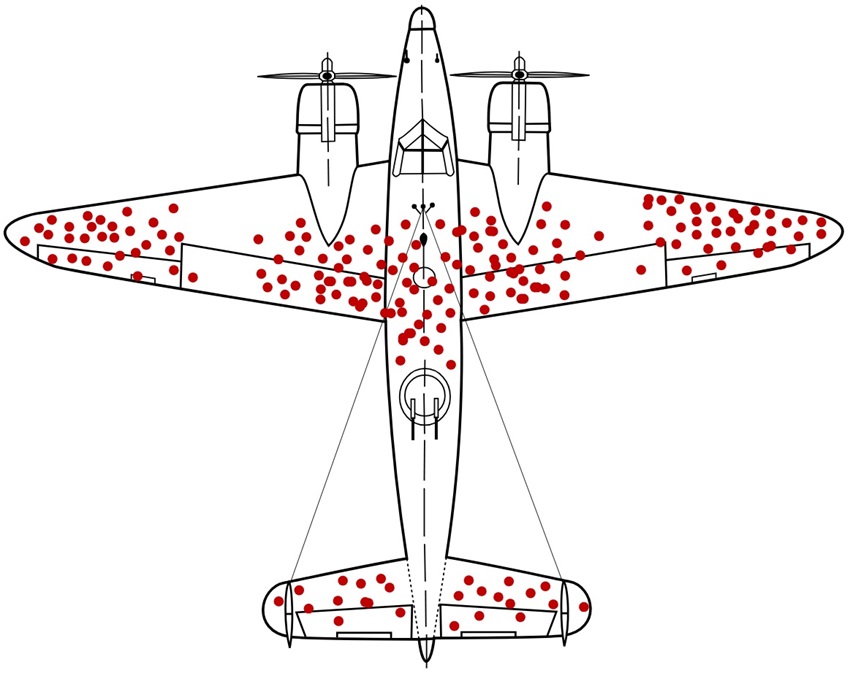

During World War II, researchers at the Center for Naval Analysis were trying to decide on where to add reinforcements to damaged aircrafts returning from their bombing missions. Reinforcements add extra weight so not all sections of the aircraft can be reinforced.

So, if you were given the task to decide, where would you add reinforcements? You’d add them to the damaged red parts of the aircraft, right?

Abraham Wald, a mathematician, and a member of the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University proposed otherwise. Because what you were looking at were biased samples of only the aircrafts that survived the battle. An aircraft got hit evenly across all sections of its body but the ones that got hit in their most vulnerable parts did not return.

The sections of the aircraft that suffered damage and were still able to return meant that they were not the weak spots you wanted to reinforce. You want to reinforce the areas that were still intact because if those areas got hit, the aircrafts did not return. The Navy followed through on Wald‘s advice which ended up saving countless lives.

This is a classic case study on how not to fall prey to survivorship bias. Because our brains are wired to take shortcuts and reach false conclusions by looking at only the samples that survived. We don’t notice the bulk of the failures – in business, in life and in war.

There are millions who play basketball but there are only a few Michael Jordans. There are millions who try their hand at acting but there are only a few Shah Rukh Khans. There are millions who drop out of school but there are only a few Mark Zuckerbergs.

Our perception of the world is completely backwards because everything we see around us is the outcome of survivorship bias. When we go to a restaurant we like, that is an example of survivorship bias. Running a restaurant is a tough, tough business and the only ones we see left standing are the ones that survived while the remaining 99 percent failed trying.

That in fact is true with businesses in general. Most businesses that start never make it past the first few years. But entrepreneurs keep trying because of the disproportionately large rewards at the other end if a business succeeds. That is a good thing, and we want more entrepreneurs to wildly succeed else no one would try.

There is a huge survivorship bias in stock investing. We see the people who did well and what sticks in our minds are the folks who bought Amazon or Microsoft at their IPOs and held their shares. But what we don’t see are the other 99 percent of the IPO investors who had their heads handed to them.

There was this story doing the rounds that goes something like this…Uncle Fred buys EMC stock twenty-five years ago and dies. His heirs discover the stock certificates in the attic, and they are worth like six million dollars. It makes the headlines, and everyone is talking about it.

What nobody talks about are the other 99 percent of Uncle Freds who bought GM or Lehman Brothers or JCPenney, and when their heirs discover the stock certificates that are now worthless, nobody tells the newspapers, and no one hears about it.

Mutual fund companies play these games well. They incubate like thirty funds and quietly wind down most of the unsuccessful ones while keeping the star performer alive. They use that fund’s performance record as a marketing gimmick to attract new money. And novice investors pile in as in anyone who invested in Cathie Wood‘s ARK set of funds lately.

The stock market is the largest creator of wealth for individual investors, but most stocks lose money through their entirety of existence. That is the nature of capitalism working its magic where a tiny minority of businesses are responsible for the bulk of the wealth that has been created in the stock market.

So, when you hear about how much this or that stock gained and how rich you would be had you bought and more importantly, held that stock, what you don’t hear about are all the losers that you also bought that you lost your shirt in.

For every Walmart, there was once a Kmart. For every Apple, there was once a BlackBerry. For every Facebook, there was once a MySpace.

Diversification is the only free lunch in investing so piling into a single stock or a sector is a statistically bad deal. That holds truer if you have already won the game. Diversification is an acceptance that the future is inherently unknowable, and that it can take many different directions.

Diversification also means not falling prey to survivorship bias because it is the failures that teach us the most important lessons – in life and in investing.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Ruyan Ayten, Pexels