Say someone you know is running short on funds and comes to you for a loan that he promises to pay back in a month. Will you lend him the money? And if so, would you do it for free?

You’d say why not. You have loaned him money before and without fail, he pays you back on time.

But say that same someone comes to you for a loan that he promises to pay back in a year? Would you loan him the money for free then?

It is different this time, isn’t it? Money loses value over time due to inflation so waiting a year means you are losing purchasing power.

And now say he comes to you for a loan that he will pay back in 10 years? The risk now just went up manyfold.

The longer the duration, the greater the chance you will not see your money back and hence, the greater the risk. And the greater the risk, the higher the interest rate you will demand on your loan.

That same thing plays out in the bond market. When you lend money, you are in fact buying a bond regardless of whether you are lending it to a friend, to a government or to a business. They do have different risk profiles as they should but inherently, it is the same thing.

United States Treasury bonds are the safest of all bonds you can buy. They range in maturity from 30 days to 30 years. A bond matures when the loan term ends.

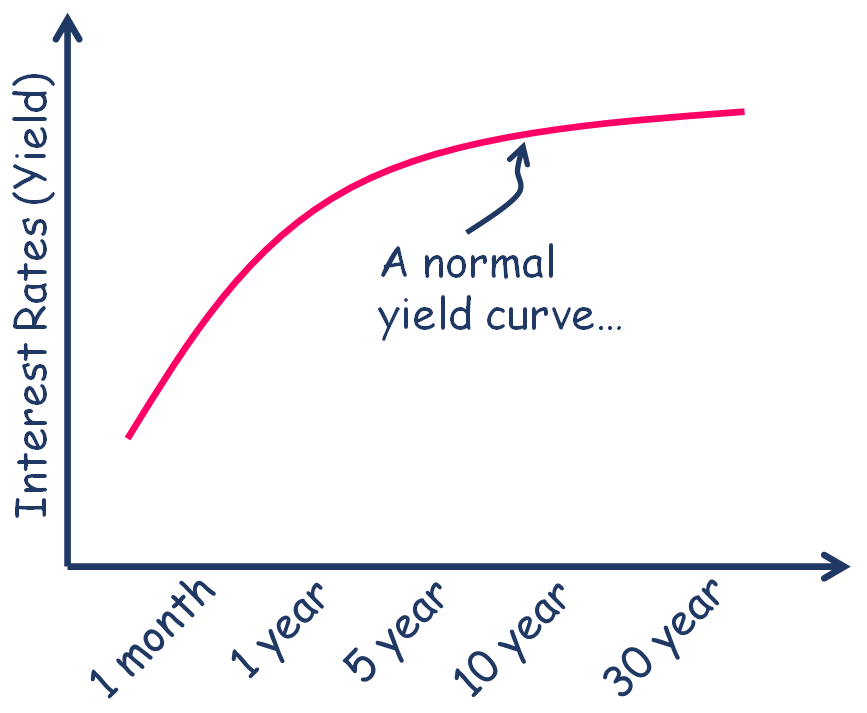

So, between say a 30-day bond versus a 30-year bond, which one do you think should pay a higher interest rate?

The 30-year bond, of course.

A lot can happen in 30 years whereas not much usually happens in 30 days. By investing in a 30-year bond, you are giving up access to your savings for a much longer duration, hence a much greater risk.

And in return, you’d demand a higher interest rate.

So, interest rates gradually slope up as bond durations rise. That is the yield curve, and it makes intuitive sense.

Now if yields on short duration bonds rise while yields on long duration bonds remain unchanged and they rise to a point where now both the short and the long duration yields are the same, that is a flattish yield curve. It does not make logical sense that that should ever happen, but it does sometimes.

But when the short duration bond yields rise to a point where now they are higher than the long duration ones, that is an inverted yield curve.

But that does not make sense. Why would a yield curve flatten or invert?

We hear about the Federal Reserve raising or lowering interest rates and we think they control all interest rates.

But they only control the overnight rates that they charge banks for the use of the money. That duration is only a day so that is the shortest of the short end of the yield curve.

Longer term rates like what we pay for mortgages and car loans are at the mercy of the markets, their expectations of growth rates and inflation.

And the Federal Reserve does not care much about the shape of the yield curve. All its charter is to make sure that the economy has full employment and stable prices.

That is, the Fed wants anyone looking for a job to be able to find one while ensuring that inflation remains tame, and deflation never takes hold. And they engineer that by manipulating the overnight rates they charge banks.

When unemployment is low, but inflation is raging, the Federal Reserve will act to slow things down and they do that by raising the cost of borrowing. Raise short-term rates with no impact on the longer-term rates and the yield curve flattens. And that can lead to a recession, so investors naturally get concerned.

But recessions are part and parcel of a healthy economic cycle. No one can predict their timing though but nothing about your long-range financial planning should change with whatever is happening to the yield curve.

Because yield curve changes are temporary while your investment timeframe is almost permanent.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – DreamLens Production, Pexels