A business makes capital allocation decisions such as expanding a factory or investing in new tech with the intent of recouping that investment over a timeframe that spans years and decades. Not all capital allocation decisions pan out but the process that is followed is with the intent of getting as high a return on investment as possible.

And the capital that a business needs can come from the profits it generates and if that is deemed inadequate, it raises that capital from the stock and the bond markets. Raising capital from the stock market means selling pieces of the business to investors while raising capital from the bond market means borrowing money from investors.

So, imagine a bank lending you money to help you buy your home and then turning around and asking for their money back the very next day? Banks of course can’t do that by law, but you see how absurd that sounds.

So why should you approach the allocation of your savings any differently? Because structurally, you are making the same kind of capital allocation decision as a business, or a bank makes which is long-term, risk-optimized and goal-oriented.

And just like how a business won’t expect a return on its investment right away, you shouldn’t either. Exchanging pieces of paper (trading your portfolio) with each other is not how you get rich.

You get rich through long-term ownership of businesses while receiving a portion of the profits those businesses generate in the form of dividends and share buybacks while letting the businesses reinvest the profits that remain, back into their respective businesses. That last part by the way is where true magic happens, not just for you but also for society.

We have it so good these days that we forget how far we have come in a mere span of a century where the poorest of the poor in most advanced economies live far richer lives than John D. Rockefeller, the richest man did in his times. He lived through life with no TV, no internet, no air-conditioning, no airplane travel, no mobile phones and not even penicillin1.

Free-market capitalism through which entrepreneurs and businesses work to find new ways to profitably invest and reinvest into their businesses to serve their customers and ultimately their shareholders is what made widespread access to all these wonders possible. We want that machine to continue churning out the goods but that takes time and is not possible with a short-term mindset.

But we are unfortunately hardwired to think only in the short term.

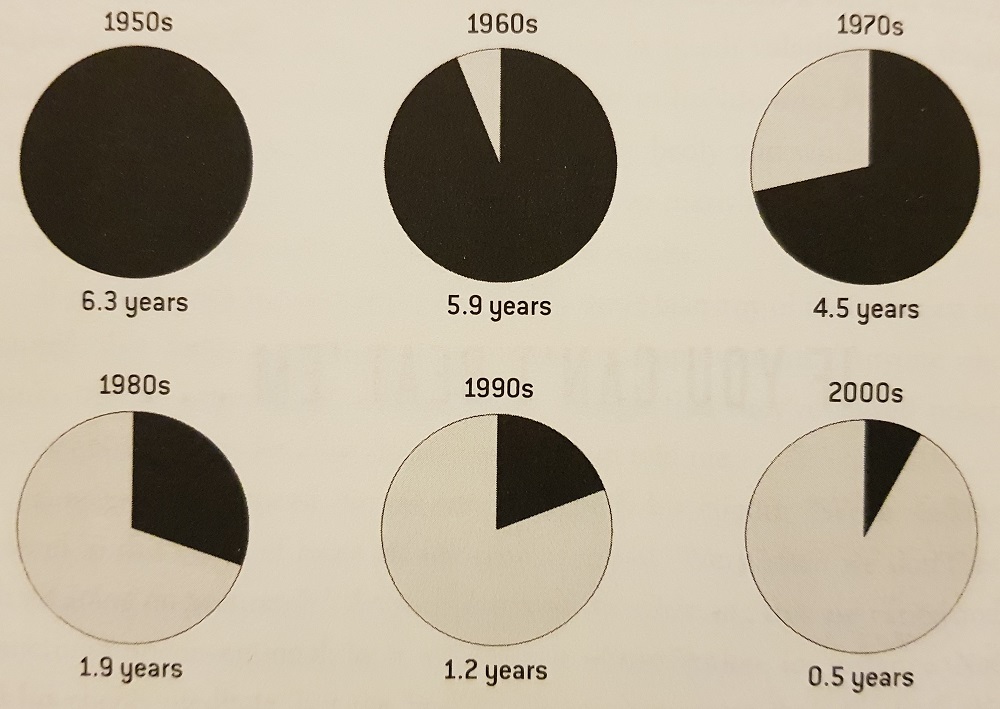

Human nature desires quick results. There is a peculiar zest in making money quickly…compared with their predecessors, modern investors concentrate too much on annual, quarterly and even monthly valuations of what they hold, and on capital appreciation.

John Maynard Keynes

And the data proves it.

The Signal and The Noise by Nate Silver

Plus, the gamification of the investing process these days with instant access and micro-second level updates to what is happening to our money does not help. It incentivizes us to act thinking that doing something helps.

But this bias towards action is poison to your money. And to the game of soccer. What?

Michael Bar-Eli, et al. in a paper published in the Journal of Economic Psychology, highlights how this bias towards action amongst elite goalkeepers hurts a team’s chance with scoring goals. Soccer as we know is a low scoring game (about 2 goals on average) where a penalty kick is a big, big deal. A team that earns it has an 80 percent chance of scoring a goal.

The stakes hence are high and pretty much all the burden of preventing a goal from being scored comes down to how the goalkeeper acts. The authors of the study analyzed data on 311 penalty kicks and found that the direction of the kicks was roughly evenly distributed between the left, center and the right quadrants of the goal box.

But the goalkeepers displayed a distinct action bias by diving to the left or to the right 94 percent of the time instead of choosing to remain in the center. Because had the goalkeepers done that, they could have saved 60 percent of the kicks aimed at the center, a far higher number than they did by diving to the left or to the right. The goalkeepers however stayed in the center only 6 percent of the time.

So, knowing that, why would they still dive rather than stand in the center? Because they wanted to appear as if they were making an effort even though making an effort was clearly disadvantageous.

Similarly, this bias towards action in investing makes us feel better, thinking that at least we are making an effort. But that is precisely the wrong thing to do, and you are likely going to do that at precisely the worst possible times.

Investing should be dull. It shouldn’t be exciting. Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas, although it is not easy to get rich in Las Vegas, at Churchill Downs, or at the local Merrill Lynch office.

Paul Samuelson

Your money is like a bar of soap – the more you handle it, the less you’ll have.

Eugene Fama

But that does not mean you don’t do nothing. There are still things that you have to get right, and they pertain more to learning how to not act than act. It is an evolutionary process that comes with time through continuous refinement until you get to a point where you are more likely to subtract and simplify than to add and complicate your money.

The outcome of the process then becomes a three-stage exercise:

- Defining a portfolio’s purpose that feeds different stages in your financial plan. Things like saving for college, buying a home, saving for financial independence come to mind.

- Building a structure that supports that purpose through those life stages as you work towards your goals. This is where you decide the splits in your investment mix and how they evolve as your life evolves.

- And only then, you go seeking investment products that fulfils that structure.

You only mess with the last stage if the products you chose have drifted away from their intended role or if any aspect of the first or the second stages change.

Let the rest of the world waste their lives chasing meme stocks and hot sectors. You work on getting the process right while refining at the margins and you’ll not only be at peace with your plan, but you’ll also be at peace with your work, your family and your life.

Cover image credit – Kuiyibo Campos, Pexels

1 David Henderson. “Richer than Rockefeller“, Econlib. February 8, 2018.