Millennials have had it rough. Between student loans and an ever rising cost of living, there is nary a chance of having anything leftover to put towards long-term goals like retirement. The struggle is real but try they must.

And then there are the lucky few who make great incomes. They are in that catbird seat of having a pile of money left over to fund their retirements.

So, say you are one of them, should you be happy then that the value of your accounts rise year in and year out? I would not be and here’s why.

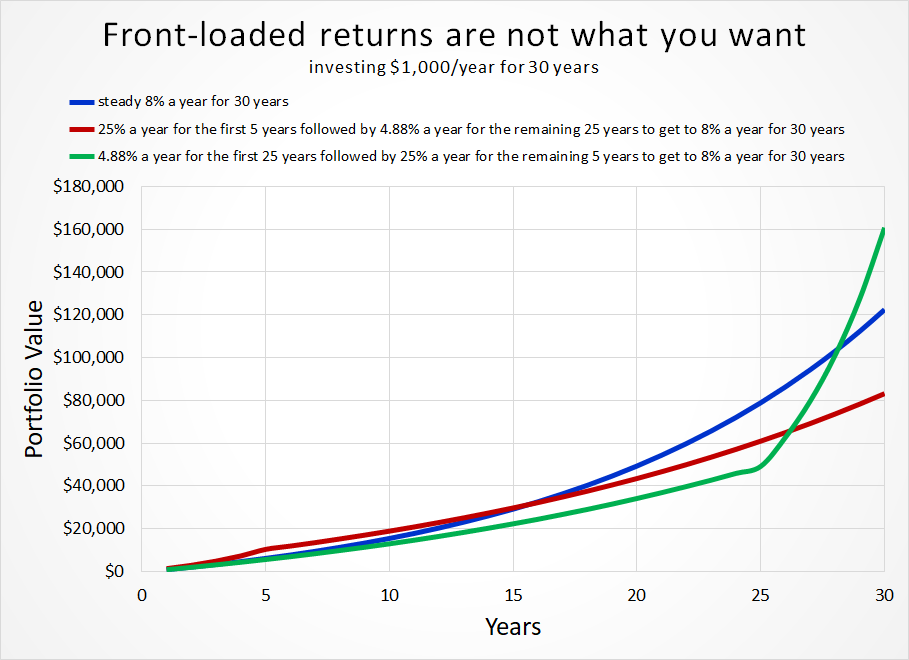

Assume that the market deals you these three scenarios:

Option 1: A steady 8 percent return each year for 30 years.

Option 2: 25 percent a year return for the first 5 years followed by 4.88 percent each year for the remaining 25 years to get to that same 8 percent return each year for the entire 30-year timeframe.

Option 3: 4.88 percent a year return for the first 25 years followed by 25 percent each year for the remaining 5 years to get to that same 8 percent return for 30 years.

If you had to choose, which one would you choose? Option two will make you fake happy now but imagine making 25 percent on a piddly amount of money that you are likely to have when starting out.

Option one is unlikely because stocks are what you’d mostly own and returns from stocks by their nature are anything but steady.

Option three will make you fake miserable now, but you’ll be glad you chose that over the other two.

That is almost double in the final portfolio’s value if most of your returns came in later than now. Imagine the difference in your quality of life, living off double the value in your retirement accounts.

Here is another perspective. Say you are in the market to buy a business that makes $50,000 a year in profits. And say you find a seller who is quoting you $500,000 for that business. So, you are paying ten dollars for each dollar in profits ($500,000/$50,000 = $10).

But for whatever reason, you decide not to go through with that purchase.

Come next year, you are in the market to buy a similar business and the same seller now is quoting that business at $1,000,000. Would you be happy paying a million dollars for a business that you could have had for $500,000 just a year back?

Maybe. Maybe not.

If that business is generating the same amount in profits this year as last, you’d be ticked because now the seller is asking for $20 for each $1 in earnings. But if the profits doubled since last year due to whatever changes the seller made to the business while maintaining that same profits multiple of ten, then it probably makes sense.

That same logic applies to buying little pieces of a business through the stock market. If the market rises because the numerator is rising faster than the denominator in the price to earnings (profits) ratio, you should be fuming mad (at everyone, of course) because you are now having to pay more for each dollar in earnings.

A short quiz: If you plan to eat hamburgers throughout your life and are not a cattle producer, should you wish for higher or lower prices for beef? Likewise, if you are going to buy a car from time to time but are not an auto-manufacturer, should you prefer higher or lower prices? These questions, of course, answer themselves.

But now for the final exam: If you expect to be a net saver during the next five years, should you hope for a higher or lower stock market during that period? Many investors get this one wrong. Even though they are going to be net buyers of stocks for many years to come, they are elated when stock prices rise and depressed when they fall. In effect, they rejoice because prices have risen for the “hamburgers” they will soon be buying. This reaction makes no sense. Only those who will be sellers of equities in the near future should be happy at seeing stocks rise. Prospective purchasers should much prefer sinking prices.

Warren Buffett in a letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, 1997.

So, if I were a millennial, I would be begging, hoping, praying for a decade long decline in the stock market that’ll allow me to pack as much money into my plan as possible.

And then when I am about to retire, I’d want the biggest bull market this world has ever seen. That would be my wish.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Blue Bird, Pexels