My first exposure to a stock market boom and bust cycle was back home in India in the early 1990s in what was deemed the ‘Harshad Mehta’ scam. It was a classic pump and dump scheme that was financed by fake bank receipts which Mr. Mehta’s firm brokered in transactions between banks. He used the money in the interim to pump up junky Indian stocks, wait for everyday folks to follow him into buying them and then sell at once, crashing their prices. He of course walked away with a boatload.

And everyone was ‘playing’ the market. The game was to buy these pieces of paper, watch their prices rise, sell, and get rich. Free money.

That party ended when the scam was uncovered. Many got wiped out. Blue-chip stocks suffered big declines.

And as it is with any big boom and bust cycle, the regulators would want to put the blame on someone. There were many to blame, including that uncle who wanted to get rich quick but then flamboyance has its costs. Harshad Mehta became an easy target. He was arrested and later died in prison at age 47, a sad end to an otherwise very clever personality.

But that was the early 90s and here we are today, and this is what a diversified portfolio of Indian stocks did since then…

That time in red with prices hugging the zero line, that was the Harshad Mehta scam.

And there were many more booms and busts since then but any money in the Indian stock market made you rich. Dividends were plenty. Tax incentives were bountiful.

The second boom and bust cycle that I intimately remember was the internet mania of the late 1990s. And luckily for me, I had no money to invest.

But that was a thing. I mean there was so much money flowing through the Silicon Valley economy that a person I knew with no intention of buying a car, goes out for lunch, test drives a high-end sports car and comes back from lunch with that car. True story, I swear.

There was so much money flowing through the Silicon Valley economy that a machine operator who worked two jobs to make ends meet, starts work at one of those jobs and walks away with stock options worth a million dollars eight months into it. True story, I swear.

The name of the game then…

It became a joke that the dot-coms that started out promising a grand vision of a more efficient way of doing business were — almost to a company — unprofitable. It’s entirely possible that a lot of them could have focused on the very real efficiencies that selling online made possible, and thereby slowly grown into sustainable businesses. But that was not the name of the game in the late nineties.

The venture capitalists who backed these companies were aiming for supernova IPOs because that’s when they got paid. Any IPO meant an exit for venture investors. Those incredible first-day “pops” that dot-com stocks experienced when IPOing? That was the early money cashing out, selling their shares to the investing public. The dot-com bubble was a fantasy period when a lot of VCs actually didn’t careif a business turned a profit, because it didn’t need to. “We’re in an environment where the company doesn’t have to be successful for us to make money,” a venture capitalist at Benchmark admitted when mulling over a pre-IPO investment in Priceline.

Brian McCullough, A revealing look at the dot-com bubble of 2000 — and how it shapes our lives today, December 4, 2018

The bubble eventually burst. Then there was so much money flowing out of the Silicon Valley economy that a person I knew, goes to a work conference with a $6.4 million portfolio on Monday, and comes back from that conference to a $1.3 million portfolio that same week. True story, I swear.

There was so much money flowing out of the Silicon Valley economy that many I knew who were about to retire had to start over.

The third monster boom and bust cycle I got to experience was of course The Great Recession of 2008. This quote by the then President George W. Bush towards the tail end of that episode said it all…

If money isn’t loosened up, this sucker could go down.

That sucker was the global financial system and our literal way of life.

And you can read all you want about that time, but you had to live through it to truly know how it felt. The stock markets would drop and drop and drop for months at end with no sign of a recovery.

Yet you had to invest because it was the best time to invest. Charlie Munger calls this the process of inversion where you invert a situation to make peace with how you decide to act.

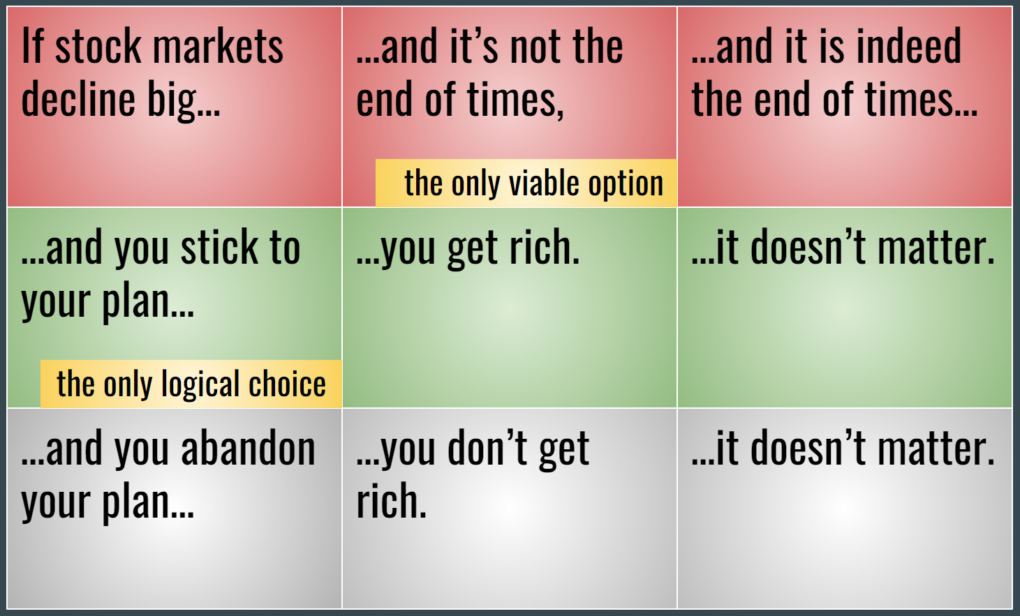

- So back to that sucker, say it did go down, then it did not matter whether you invest or not.

- But if the sucker did not go down, then you’ll come out at the other end far richer.

Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French mathematician posits that if you had to wager on the existence of God, which side should you bet on? That decision making quandary, called the Pascal’s Wager, explained…

If God is not, whether you lead your life piously or sinfully is immaterial. But suppose that God is. Then if you bet against the existence of God by refusing to live a life of piety and sacraments, you run the risk of eternal damnation; the winner of the bet that God exists has the possibility of salvation. As salvation is clearly preferable to eternal damnation, the correct decision is to act on the basis that God is.

An excerpt from one of the best books on understanding risk, Against the Gods by Peter Bernstein

The Pascal’s Wager version for our money…

So, during times of market mayhem, you stick to your plan and it is not the end of times then you get rich. There is no other option.

Large market declines are normal because market is made of people and people go crazy from time to time.

If you’re not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century you’re not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you’re going to get compared to the people who do have the temperament, who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.

Charlie Munger

And when they do, remind yourself of Pascal’s Wager and invest away.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit: Jonathan Petersson, Pexels