If you are into weight training, you know that if you want to increase muscle size and strength, you must lift heavy. Heavy to a point of discomfort. Heavy to a point of pain. Not that I would know but that is what I’ve heard.

The same applies to investing. You must be willing to endure occasional discomfort and sometimes pain on this journey to financial independence (we should stop calling it retirement).

And unless you are doing something crazy with your savings, most of that discomfort/pain is plain vanilla asset price volatility.

So, what determines an asset’s price? But before that, what is an asset? Or to be even clearer, what is an investible asset?

For an asset to be investible, it must produce cash flows. Or it should have the prospect of producing cash flows.

A painting is not an investible asset. Cryptos, NFTs and anything that anyone cooks up and brings to the market with never any prospect of producing cash flows are not investable assets.

A share in a business on the other hand is an investible asset. So is a bond issued by that business. The home you own is an asset. They all directly or indirectly produce cash flows or have the prospect of producing cash flows.

And what determines an asset’s price? Take that share in a business that trades on a stock exchange for example. Millions of market participants at any given point in time are crunching their own numbers and their collective opinions about that business’s value gets reflected in its stock price we see quoted on that exchange.

The quoted price is mostly right but not always. That’s knowable only in hindsight.

In the long run though, the price of that asset and its value will converge. And we invest with that in mind.

Talk about valuing an asset, the basic building blocks are the same – be it a stock or a bond or real estate.

We first estimate an asset’s future cash flows. And since we hate waiting for those cash flows to hit our bank or brokerage accounts, we value them less the longer we have to wait.

That is, we devalue or discount the cash flows that arrive way out in the future more than the ones that show up say, next year.

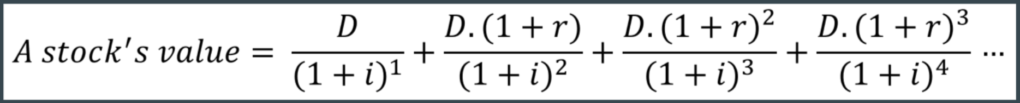

We’ll use valuing stocks as an example.

Though inherently simple, there is a lot going on there. Ignoring book value (buildings, machinery etc.) for now to make the math simple, stocks as we know are long duration assets – perpetuities in theory with cash flows that go on forever. That is what the three dots at the end signify. The cash flows continuing forever is not true for every stock but for a portfolio of stocks, that assumption holds true.

And by design, stocks are ideal as long-term investments. You don’t start a business and expect it to turn a profit next year.

So, every time you put new money into your 401(k), you are indirectly providing capital to a new or existing business to try something new, to explore a better way of doing the old thing, to invest in R&D that someday cures cancer, to make us into a space faring civilization etc. etc.

All that takes time.

So, don’t go near the stock market expecting a return in a year. In fact, don’t go near it if you expect something out of it in less than five years.

But back to the valuation model, the D is the first year cash flow (dividend). Stocks eventually in some form or the other pay out all the accumulated profits back to the shareholders in the form of dividends. Not every stock does but a collection of stocks eventually will.

And as the businesses that you own through your stock ownership grow, the dividends grow and that’s captured by the dividend growth rate, r.

Then there is the discount rate, i. Discount rate is many things. It is the opportunity cost of what else could you have done with that money that you are buying those stocks with. It is the return you expect from that investment. And what you expect as a return is a cost to a business you own through your stock ownership so it is also the cost of capital for that business.

And when you think about opportunity cost, you also need to think about risk. Dividends are not certain. The growth rate of those dividends certainly is not.

And depending upon the type of stocks you own, the certainty of dividends and the certainty around the growth rates of those dividends vary.

Johnson & Johnson is in a different league of dividend payers than say, Juniper Networks. Which one would we ascribe a lower discount rate to? Johnson & Johnson of course.

And discount rate being in the denominator means for the same set of cash flows, we’ll ascribe a higher value to Johnson & Johnson as a business than Juniper Networks.

Now the opportunity cost. It is one thing to be gung-ho on stocks when bonds pay nothing. Because there are not many viable options. That has been the world for so long that we have a hard time imagining there could be alternatives.

But when interest rates on super-safe Treasury bonds rise, now we have choices. Why would we invest in stocks when Treasury bonds yield say 8 percent? With zero risk? That’s not to say that we are there yet but you get the point.

So, the discount rate, even for Johnson & Johnson rises when interest rates rise. And the value of that business hence, declines.

And we do not even want to imagine what that does to a no-moat, money-hemorrhaging startup du jour. Its valuation gets obliterated.

So, some takeaways…

- If your net worth is under $100,000, the fastest way to get there is through increased income via career growth or entrepreneurship and not through investment returns. The same applies if your net worth is under a million dollars. Markets will do whatever they’ll do but the two things you can control are how much you make and how much of what you make, you can save. The rest is all noise. So, do not mess around.

- Investment superstars come and go but mean reversion is here to stay. Do not be enamored by anything or anyone that has shot the daylights out of what normal investing should normally yield. If the risk-free rate is 3 percent and you got 30 percent, do not be shocked if and when that eventual mean reversion happens. Free lunches are few and far between, especially in the money world.

- Never, ever, ever, ever, never, ever be completely in or out of the markets. All it takes is 5 minutes of looking up to realize that market timing has never worked and will never work. The only thing you can and should do is adapt your plan to what your gut can handle. It is one thing to fill out a risk tolerance questionnaire and assume that you can handle double-digit declines in your portfolio’s value. It is an entirely different ballgame when you are experiencing that. So, take notes and implement changes if necessary.

- Naval Ravikant, the founder of AngelList says that investing favors the dispassionate. That is, markets tend to efficiently separate emotional investors from their money. So, don’t let Mr. Market take advantage of your anxiety and fear. The only way to get around that is through a well-crafted investment policy statement and a plan. And then when Mr. Market goes through its usual manic-depressive phase, you go revisit that to see if changes are necessary. If not, sit tight and don’t peek.

- Of course, think long term. John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, once said that the daily machinations of the stock market are like a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Nothing about the businesses you own changes that much from one year to the next. Capitalism is here to stay and business ownership is where the bulk of the riches lie. Either you can be a cog (worker) in that wheel or own a piece of that wheel. Own that piece at every chance you get.

- And last, there are three ways to go broke, a la Charlie Munger – liquor, ladies and leverage. No comments on the first two but leverage will eventually kill. It works like a charm when all is going well and then you go broke overnight. Use it sparingly.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Julia Larson, Pexels