My first tryst with a stock market boom-bust cycle was back home in India during the early 1990s in what was deemed the ‘Harshad Mehta’ scam. It was a classic pump and dump scheme, financed by fake bank receipts which Mr. Mehta’s firm brokered in transactions between banks. He used the money in the interim to pump up junky Indian stocks, wait for everyday folks to follow him into buying them and then sell all at once, crashing their prices. He of course walked away with a boatload.

And it seemed everyone was ‘playing’ the market. The game was to buy these pieces of paper, watch their prices rise, sell, and get rich. Free money.

That party ended when the scam was uncovered. Folks who levered up were wiped out. Even blue-chip stocks suffered big declines.

And as it is with any widespread boom and bust, regulators had to find a scapegoat. And there were many co-conspirators including that uncle who wanted to get rich quick but then flamboyance costs. Harshad Mehta was an easy target. He was arrested and later died in prison at age 47, a sad and an early end to an otherwise clever personality.

But that was the early 90s and here we are today, and this is what a diversified portfolio of Indian stocks did since then.

That highlighted timeframe in red with prices hugging the zero line, that was the Harshad Mehta scam.

And there were many more booms and busts since then but any money in the Indian stock market made you rich over time. Dividends were plenty. Tax incentives were bountiful.

The second that I intimately remember was the Dot-com boom and bust. And lucky for me, I had no money.

But that was a thing. I mean there was so much money flowing through the Silicon Valley economy that a person I knew goes out for lunch, happens to test drive an expensive sports car on the way there and comes back from lunch with that car. True story, I swear.

There was so much money flowing through the Silicon Valley economy that a technician who worked two jobs to make ends meet, starts work at one of those jobs and walks away with stock options worth a million dollars eight months into the joining. True story, I swear.

The name of the game then,

That bubble of course eventually burst. And once it did, there was so much money flowing out of the Silicon Valley economy that a person I knew goes to a work conference with a 6.4 million dollar portfolio on Monday, comes back from that conference to a 1.3 million dollar portfolio later that week. True story, I swear.

There was so much money flowing out of the Silicon Valley economy that I knew someone who had it made, having to start all over at age 55.

The third monster boom-bust episode during my time was of course The Great Recession. We were on the verge of la-la land. The tail-end of that spectacle was summarized by the then President George W. Bush with this one statement,

“If money isn’t loosened up, this sucker could go down.”

That sucker was the global financial system and our literal way of life.

And you can read all you want about that time, but you had to live through it to understand how it felt. The stock markets would drop and drop and drop for months at end, but you had to keep on buying because you had no choice.

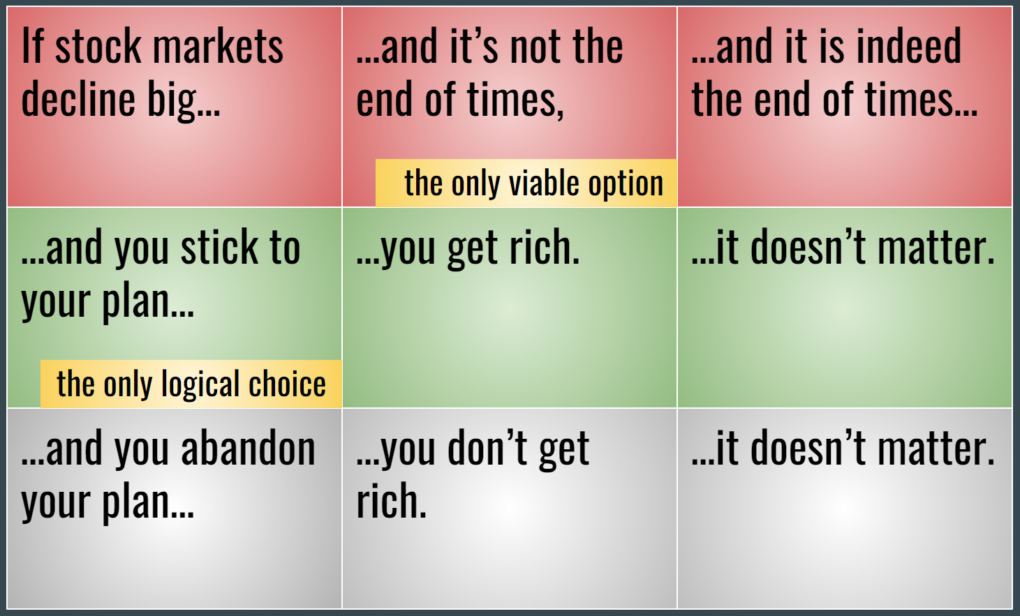

Charlie Munger calls this decision-making construct in times of crises a process of inversion where you invert a situation, any situation to make peace with what you decide to do.

- So, say if the sucker did go down, then it did not matter whether you invested or not.

- But if the sucker did not go down, then things would be alright, and you’ll be rich.

Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French mathematician and a Catholic theologian posits that if you had to wager on the existence of God, which side should you bet on? That decision making quandary, called the Pascal’s Wager, is cited in Against the Gods by Peter Bernstein,

“If God is not, whether you lead your life piously or sinfully is immaterial. But suppose that God is. Then if you bet against the existence of God by refusing to live a life of piety and sacraments, you run the risk of eternal damnation; the winner of the bet that God exists has the possibility of salvation. As salvation is clearly preferable to eternal damnation, the correct decision is to act on the basis that God is.”

The Pascal’s Wager‘s version for our money,

So, during times of market mayhem, you stick to your plan and it is not the end of times then you get rich. There is no other preferred possibility.

And if you are a long-term investor in stocks, experiencing a large market decline is a matter of when, not if.

“If you’re not willing to react with equanimity to a market price decline of 50% two or three times a century you’re not fit to be a common shareholder and you deserve the mediocre result you’re going to get compared to the people who do have the temperament, who can be more philosophical about these market fluctuations.”

Charlie Munger, Vice-chairman, Berkshire Hathaway

And how else are you going to beat inflation. The stock market is it. You get ownership stakes in businesses. Businesses generate profits. They grow those profits that in the long run outpaces inflation. You own those profits.

You could own bonds, but a fixed rate of return is all you get. They cannot out earn stocks by design. They don’t jump around a lot, but you pay through the nose for that apparent safety.

There’s real estate but it does not cash flow out enough to bear the risks. And the work. And the hassle. Plus, there is a lot of indirect real estate exposure in your stocks. And you likely own a home. That is all you need.

How much stocks to own depends upon where you are in this lifecycle of investing. But abandoning them when times get rough is the last thing you should do.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit: Jonathan Petersson, Pexels