Buying businesses (stocks) is not about winning popularity contests. In fact, the more popular a stock or a category of stocks gets, the less likely its price matches its value. Pay too rich a price for a popular stock du jour and you could be sitting on that stock forever, never to be made whole.

A great business, hence, does not a great stock make. Take Cisco Systems for example. Cisco Systems, as we know, supplies infrastructure that powers the internet economy. They are of course not the only ones. They have competition but by far they are the biggest of them all.

And you don’t just wake up one day and decide to compete with Cisco Systems. You need engineering. You need services. And above all, customers need to trust you to provide them with reliable products that won’t bring down their networks. If you want all of that, Cisco Systems is your place to go. It is as predictably profitable and as moat-infused a business as any business can get.

At the peak of the Dot-com boom in the year 2000, Cisco stock was selling at triple-digit multiple of profits with its total market capitalization eclipsing $600 billion. Market capitalization is the price quoted for a business on the stock exchange on any given day so if you wanted to buy Cisco Systems as a business in its entirety, you would have needed six-hundred billion dollars.

That was the quoted price but was that the right price? In hindsight, clearly not. Cisco trades today1 at less than a third of its market price of almost a quarter century ago. Will it ever see the old highs again? Never.

And there was never much wrong with the underlying business. It made billions in profits and still makes billions in profits. It is just that the market at the time priced the business far, far away from its true intrinsic value. The market was clearly wrong then and possibly right today, but we can only know that in hindsight because predicting profits years and decades out is a near impossible feat.

But could you have bypassed that train wreck had you done some basic back of the envelope math? Maybe.

I say maybe because we can do Monday-morning quarterbacking all day long but when we are in the heat of a stock market mania, who knows what we’d really do and what theories we might concoct to justify any valuation. And the heat at the peak of that mania was intense.

So, here is how you could do a first-cut analysis on any stock you are considering buying. The first thing is to always evaluate your buying decision as if you are buying the entire business. That is regardless of how small or big of a stake you plan to buy in that business.

Then consider your payout timeframe. I have talked about this before but say you are in the market to buy a corner gas station and it costs a million dollars.

Now if you invest a million dollars, you want that gas station to get you back your million as soon as possible.

So, say it takes ten years for that gas station to generate enough profits that equals your initial investment. That is your payout timeframe.

Once your initial investment comes back to you in the form of profits, only then do you really start making a net return on your investment. This math of course ignores opportunity cost and the hassles of running a business so if you were to factor that in, you would need that payout timeframe to be a lot quicker but let us ignore that to keep the math simple.

So back to buying Cisco at the then quoted price of $600 billion and if you were looking for a ten-year payout, you were expecting that business to return $60 billion a year in profit for ten straight years. Only then, you’d start making a return on your original investment.

Cisco’s profits in the year 2000 were about $3 billion, a far cry from the multiple tens of billions of dollars you should have expected in theory. And $60 billion a year in profit was and is a gigantic number for any business to sustainably deliver for that long a timeframe.

So of course, it was an insane valuation from a payout perspective and that is the only perspective that eventually counts.

That was the Dot-com bubble, and you’d think we would have learnt our lessons but here we are. In fact, the insanity of the last few years is at another level. I don’t recall ever a time in history with so many businesses priced at tens of billions of dollars but with a nary a sight towards making a profit.

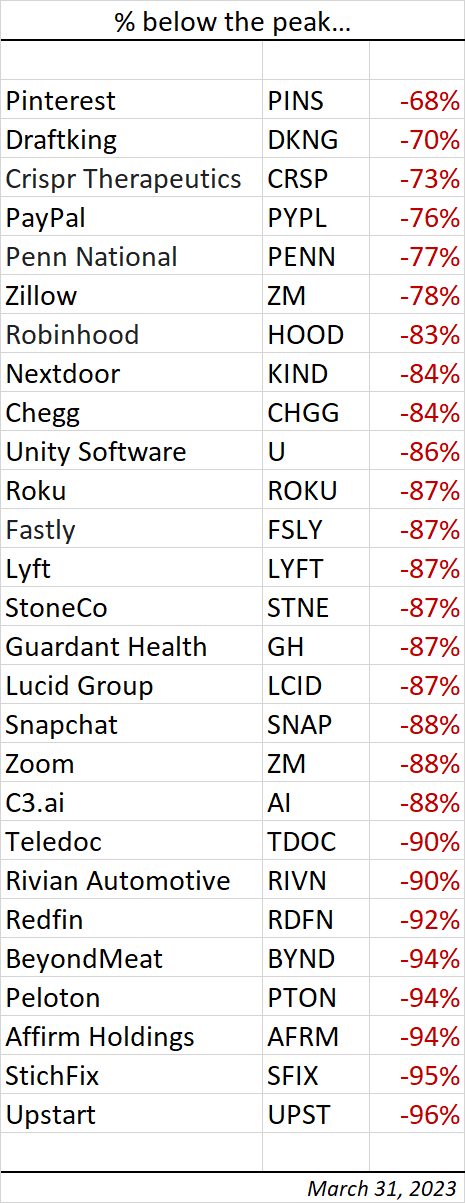

And when the market eventually comes back to its senses, the consequences can be brutal. The list below highlights some of the names that were insanely priced and the after-effects of what happens when the market resets its expectations.

And it is by no means a comprehensive list.

This is not to say that all these businesses are hurting. The businesses can continue to otherwise thrive. It is just that their stock prices ran way ahead of their true fundamental value and now prices are reverting to meet that value.

Often though, a stock price faltering can falter a business. With a big chunk of key employee compensation especially in the growth, tech space, tied to employer stock, when the stock price falters, they leave. That in turn creates a self-destructive downward spiral towards mediocrity. And eventually, insolvency.

Bubble stocks, once they collapse, seldom recover. So, if you are holding on to them thinking that you’d be made whole someday, you could be holding forever. That while the rest of the economy continues chugging along.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Mary Taylor, Pexels

1 March 31, 2023