Cockroaches are the ultimate survivors1. They can live without air for up to an hour, without food or water for months. They can survive the Arctic cold. Ice ages and continent shifts mean nothing to them. It’s no surprise then that the cockroach as a species has been around for 300 million years. And it is not going anywhere anytime soon.

Your savings should have the same survivalist foundations as that of a cockroach. No matter what the world throws at it, your savings must survive.

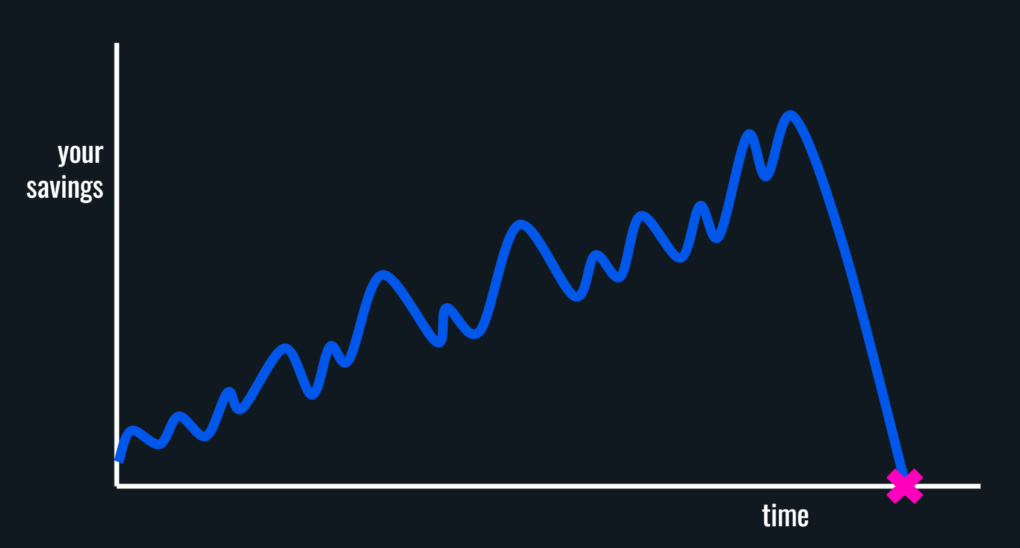

So never set yourself up for a catastrophe like this…

And catastrophes like these happen all the time. Leverage, which is borrowing money to invest, is many a times to blame.

Tying up a big chunk of your net worth in one or two stocks is another very common cause. That is taking on unsystematic risk at its core and the results could be life-altering…

Former Enron Corp. employee George Maddox, who lost his retirement savings when the energy giant collapsed, says he has been forced to spend his golden years making ends meet by mowing pastures and living in a run-down East Texas farmhouse. Maddox, who served 30 years as a plant manager with the company, was long retired as Enron began spiraling out of control in the months leading up to its bankruptcy on Dec. 2, 2001. With all his retirement savings tied up in 14,000 shares of company stock, then worth more than $1.3 million, Maddox says he never saw the crash coming.

10 YEARS LATER: What Happened To The Former Employees Of Enron? Business Insider, December 1, 2011

I know of someone who went from $4 million in their employer stock to zero in six months. If you have seen some of the headlines circulating around bank failures lately, you’ll know which one did it. That is literally all the money they had so life-altering is the least bad way I can describe it.

Unsystematic risk, in plain English, means you cannot predict the good (or the bad) about a stock for long into future. You can do that with a basket of stocks (businesses) but with one or two stocks, in this day and age of hyper-rapid disruptions, not as easy.

And most of the single-stock risk unknowingly creeps up on you if you get paid in employer stock. You must then diversify out of it because for every story that pans out great, there are many more that fizzle out.

And when your employer’s story fizzles out, you lose the money invested in their stock. And your paycheck. And health insurance. And the rest.

And regardless of how much you believe in the business you work for, it won’t be around forever. Things change, key employees leave, and competition is always waiting at the heels to eat into whatever moat your business currently enjoys.

Plus, drawdowns (declines) are deeper with concentrated portfolios with no guarantee of a recovery. That reversion to the mean (more on this later) that is so ingrained in the design of most broad-based portfolios could never happen to you.

Talk about drawdowns, you know that had you invested in Apple stock 20 years ago, you’d now be a gazillionaire. But go back another 20 years and say you bought $10,000 worth of Apple stock on April 1, 1983, guess how much money you’d have 20 years later?

$8,400.

Are you telling the world that you would have the necessary fortitude to hold on to a “loser” for 20 long years while the rest of the world gets rich? Not a chance.

Plus imagine the lifelong guilt and literal trauma you’d be living with, had you waited for 20 long years, only to eventually bail on that “loser” and then watch it soar to become the most valuable business in the world.

So do individual stocks ultra-sparingly and if you do do it, do it with a teeny-tiny portion (I say less than 5%) of your money with the intent of holding forever. If those stocks go nowhere, fine. You’d still have the bulk of your savings invested rightly that circumvents all these procedural and behavioral vagrancies.

And when I say do individual stocks, do it with stocks that can matter. Because you are looking for that lottery-kind of outcome to get compensated for taking on stupid risk.

Hence, you can’t be holding a trillion-dollar market value stock because for that stock to double your money, it needs to become a 2 trillion-dollar stock. How many 2 trillion-dollar stocks do you see around?

And you likely own that trillion-dollar stock by the boatload anyway if you’ve built a half-decent portfolio. So, if it were me, I’d own small, obscure stocks (not junky penny stocks) that have a shot, regardless of how faint, to do 10 times your money in 10 years.

Reversion to the mean…

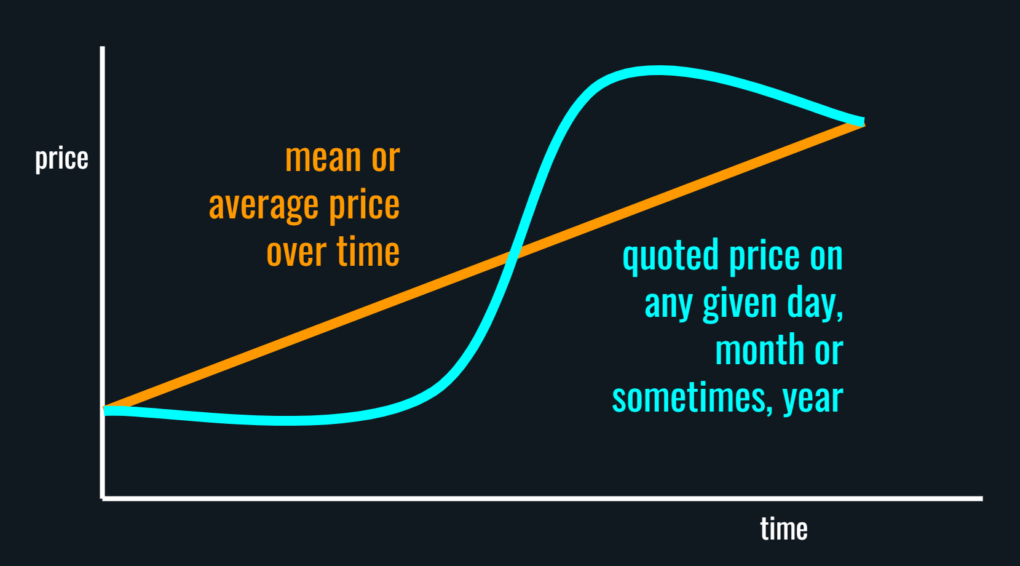

I passingly referenced to reversion to the mean but that is something that needs more explaining. Reversion to the mean assumes that the value of an investment, even if it were to decline, will eventually revert back to it’s long-term trajectory of perpetual growth.

You can’t assume that with individual stocks because stocks go down all the time, never to recover. But with a portfolio of stocks that are at the top of our ever-evolving economic value chain, they can go down but will eventually recover. They must recover unless you think it’s going to be the end of the world.

That reversion to the mean backdrop is what then allows you to confidently dollar cost average into your plan, knowing full well that in the long run, the collective prices of the investments you own, will recover.

The right risk…

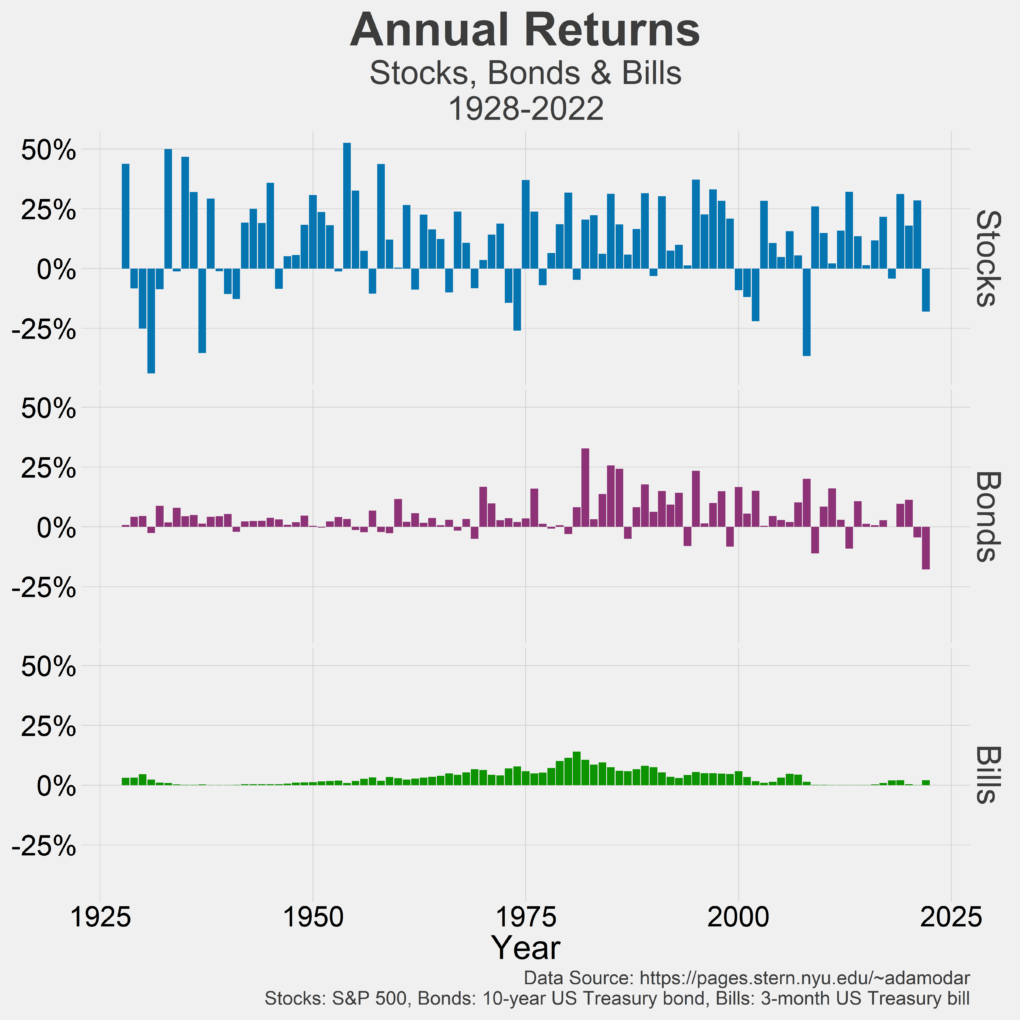

There is no getting around taking on some risks though because why should you get paid to stuff your savings in a bank account? We call taking on the right risk, market risk or systematic risk.

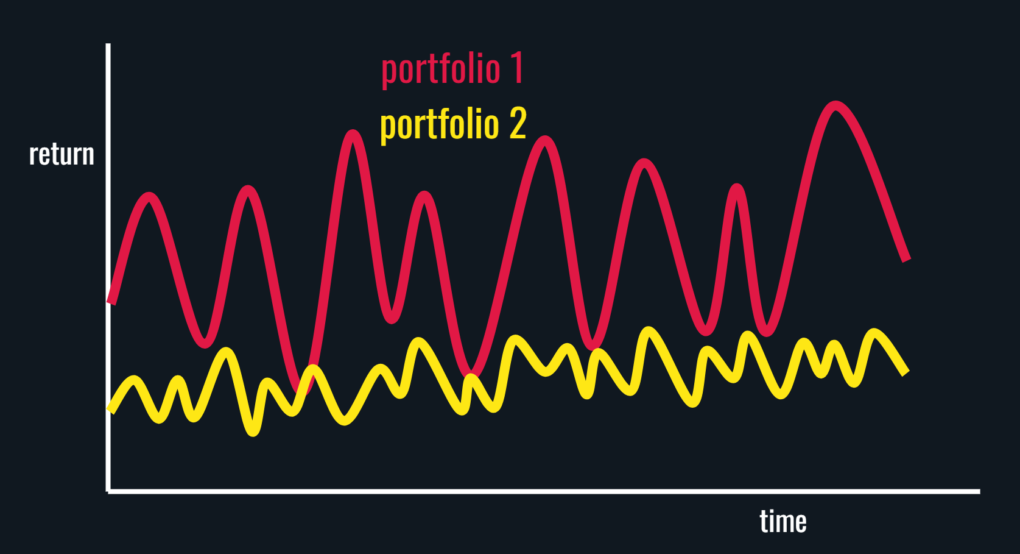

Systematic risk is how much the returns of a category of investments vary around its average. Statisticians call that variance. We call it volatility.

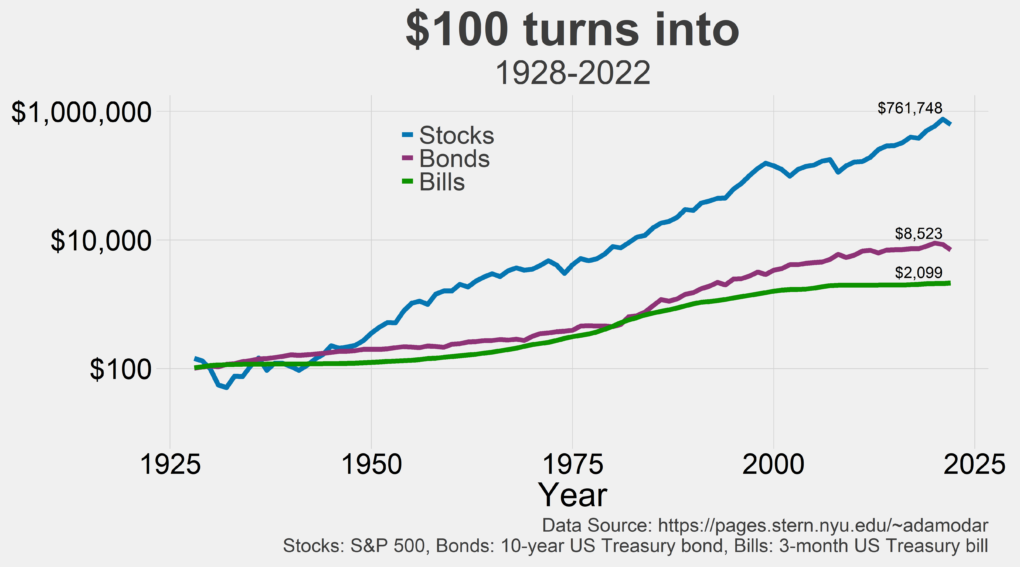

We all know about the S&P 500 index. It represents a collection of 500 of the largest publicly-traded businesses (stocks) in United States. We’ll use that as a proxy for stocks in the discussion that follows.

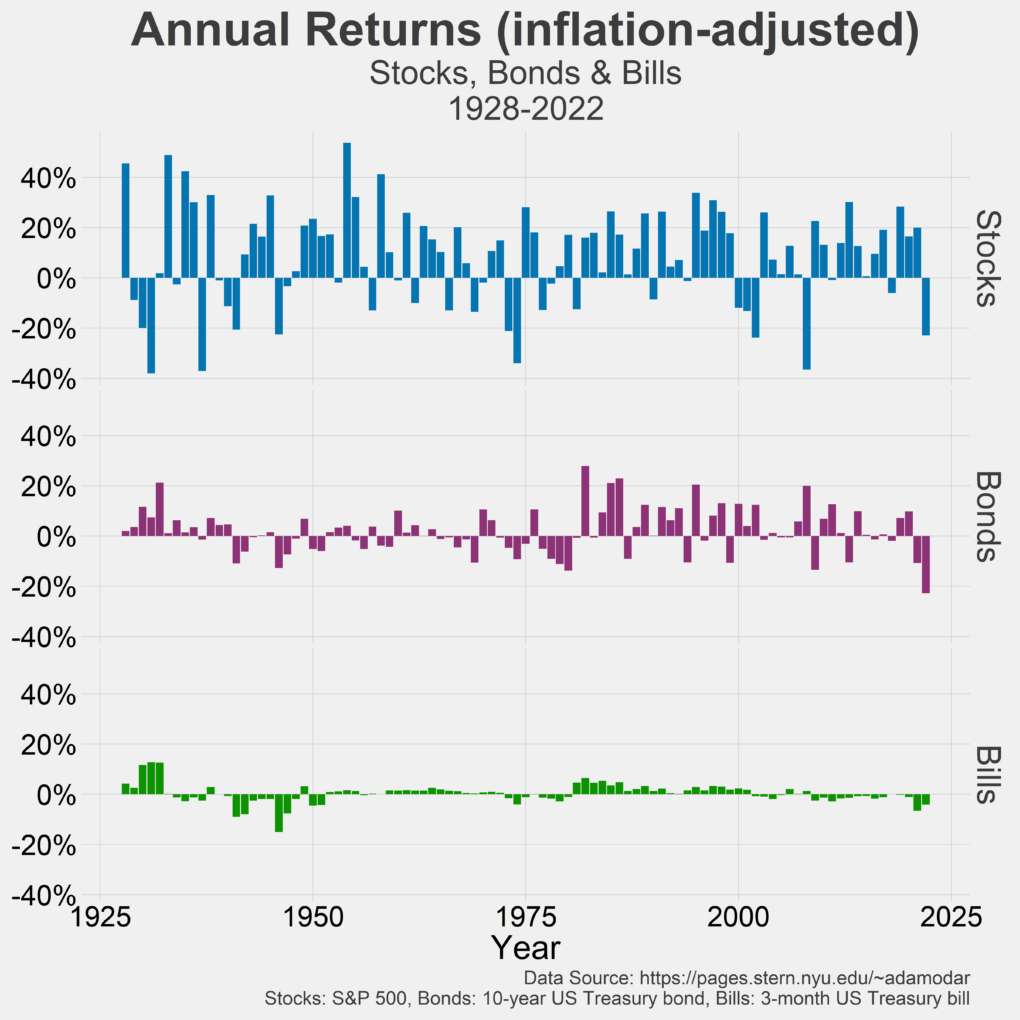

S&P 500 has returned on average around 10% each year since 1928. But you seldom ever get 10% exact in any given year because stocks are volatile. That volatility is systematic risk and since S&P 500 is deemed the de-facto barometer for the stock market, that risk is also called market risk.

Stock markets are manic depressive beasts. One moment, they see nothing but prosperity. The next moment, they foresee nothing but doom. Volatility, hence, is inherent with the stock markets because peoples’ perception of a stock’s value changes from time to time.

So if the heat with owning stocks gets too intense, you turn to the next rung on that systematic risk ladder by buying say Treasury bonds (long-term government bonds). They can get volatile but not as much as stocks.

Or if you want to completely turn off volatility, you get to the safest of all investments, Treasury bills (short-term U.S. government bonds). This is the same as holding cash.

But safe is expensive, very, very expensive…

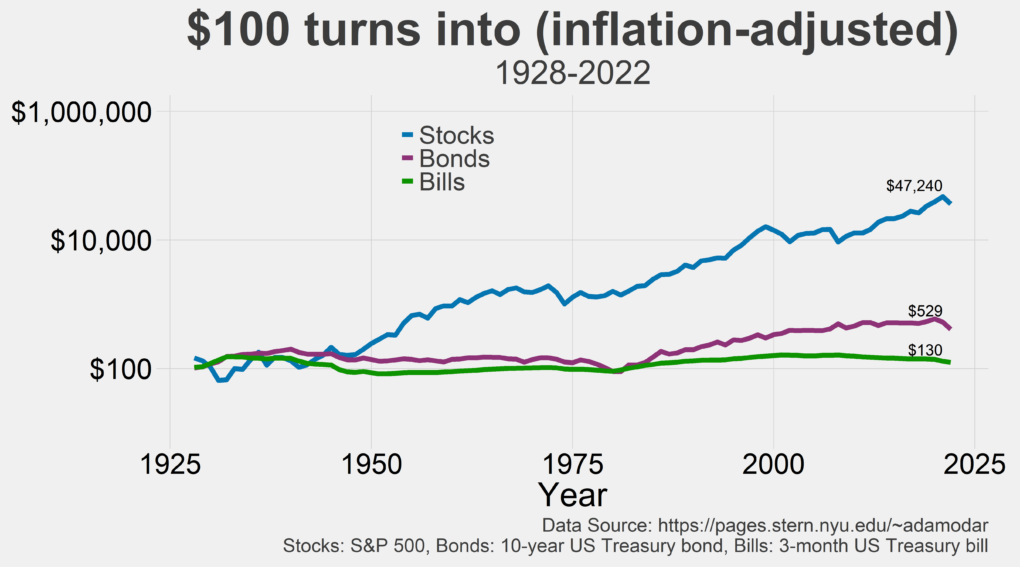

But even the supposedly safe bonds become unsafe quick once you factor in inflation…

But you seldom see that volatility because no one reports after-inflation returns.

But after-inflation gains in wealth is all that ultimately counts.

So turn off volatility too much and you won’t be able to keep up with inflation and hence a need for balance between risk (volatility) and return.

And you get that balance by adding bonds to an all-stock portfolio in just the right proportion that helps you sleep well at night. You won’t earn as much but that’s not always the goal.

And every decently diversified category of investments would have its own systematic risk-return relationship and you’d want to include several of them to build out a good plan.

Capital Market Line…

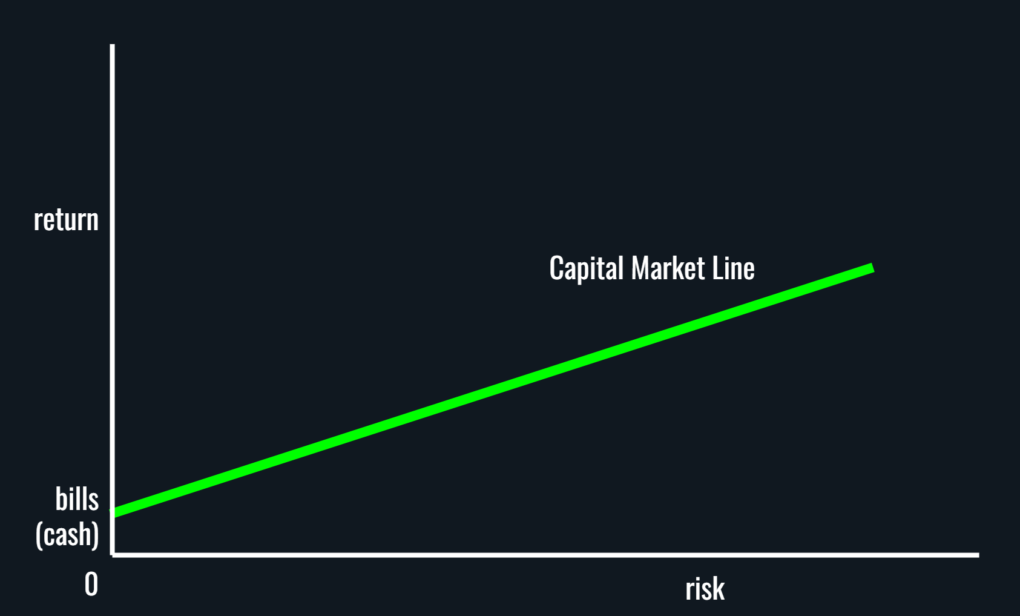

We hear it all the time that the more risk you take, the more money you make. Finance nerds call this the Capital Market Line.

It starts at the left with ultra-safe investments and rises to the right with incrementally riskier investments. Treasury bills are short-term government bonds. You have to try real hard to lose money with them…before inflation of course.

So what intuitively comes after that on that risk-return line? Long duration bonds (10-year Treasury bonds for example) because as a bond’s investment timeframe rises, its risk rises.

Then there are municipal bonds, high-quality corporate bonds, emerging markets bonds and junk bonds. As a bond’s credit quality worsens, its risk again rises.

So you see that Capital Market Line form for bonds.

Stocks are long duration assets which means you need to own them for years to reap any significant rewards. Plus direct and indirect cash flows (dividends and buybacks) with stocks are more unpredictable than interest income from bonds.

So quite naturally, stocks are riskier and hence will lie to the right of most bonds on that Capital Market Line.

And even within stocks, you’ve got domestic stocks, international stocks, emerging market stocks, small company stocks and so on, all on that Capital Market Line with steadily rising risk profiles.

At the extreme right, you’d find things like private equity and venture capital. That’s assuming you can get a broad enough exposure to them else you are back into the unsystematic risk world. They are not investible yet so anyone pitching them to a lowly you means you are going to get ripped off.

So that’s your complete Capital Market Line.

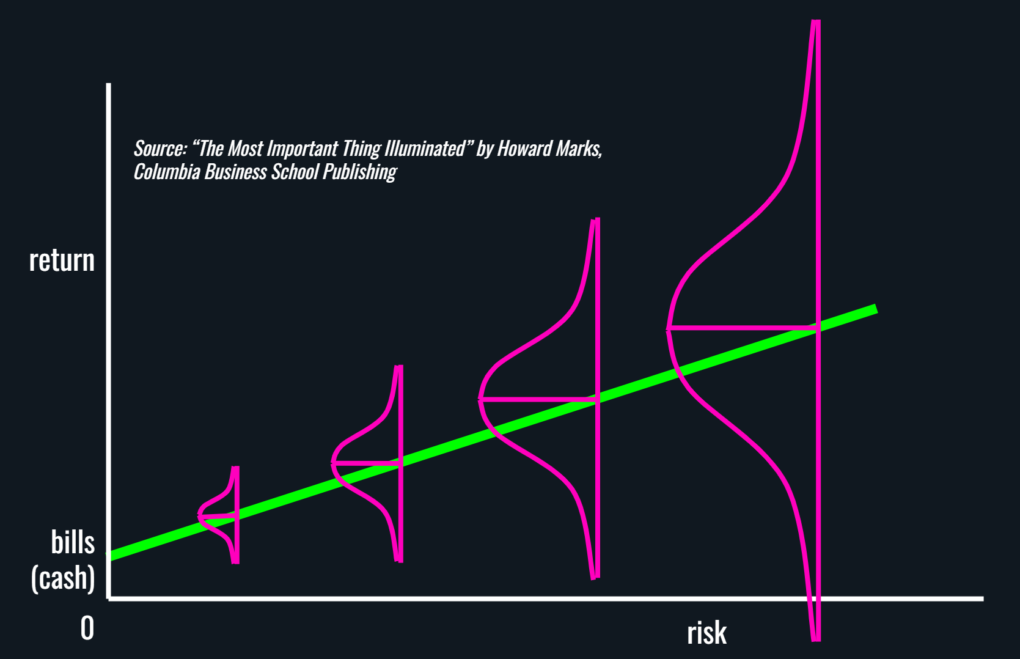

But just because you take on more risk does not mean you are owed a reward because if riskier investments were guaranteed to earn more, investors would bid up the prices of those investments to a point where no excess return exists.

The correct formulation then is that in order to attract capital, riskier investments have to offer the prospect of higher returns2. Not a guarantee but a prospect.

And that’s when we come into the world of distributions instead of point estimates to re-form that risk-return relationship.

The revised Capital Market Line hence…

So, with all that in mind, zero risk is not an option. And stupid risk is out the door as well. What you need is just the right amount of risk to get you from where you are to your goals. It’s mostly (not always) a downward sliding scale of risk as you age towards your goals, the most expensive of them being retirement.

And it is the most uncertain. How uncertain? Let’s compare planning for retirement (I prefer to use financial independence instead) with planning for say, college. There is not much uncertainty with college planning. You know precisely when that kid is going to enter college and when paying for it will end. And you can work around the expenses by the kind college you can afford.

Not as clear with retirement because you don’t know how long you need to plan for.

But there are some guideposts you can use to engineer the right amount of risk and it all comes down to your expenses. How much does it cost to afford your version of a good life? If it costs 2% of your money each year, no problem gorging on the max amount of risk with say an all-stock portfolio. Just be prepared to leave a big, big pile of money behind.

If your all-in expenses run at 3% of your money, you start to consider some allocation to bonds. At a 4% withdrawal rate, a decent allocation to bonds becomes a necessity. Go beyond that and you face the real risk of outliving your money. It’s not as cut and dry as that because factors like the interest rate environment you retire into, the richness or cheapness of investments at the time and if other sources of income exist can change that math but you get the point.

And it goes without saying that your savings rate can smooth out all sorts of imperfections. Plus, the fact that you get used to saving a big chunk of your income while working means you’ve designed your version of the good life that doesn’t cost as much. Which then means you won’t need as much money to retire with. Your independence hence, can come far sooner than planned.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Erik Karits, Pexels

1 Loren Grush. “The Verge review of animals: the cockroach“, The Verge. January 17, 2016.

2 Howard Marks. “The Most Important Thing Illuminated“, Columbia Business School Publishing.