Let me introduce you to Jason. He retires in the year 1969 with today’s equivalent of a million dollars. That is, he retires with an amount of money that has the same purchasing power as what million dollars buys today.

And he knows a thing or two about the ravages of inflation and hence, to preserve his purchasing power, he has his entire portfolio invested in the stock market.

He has also heard about the 4% rule. That is, if he were to draw 4% from the starting value of his portfolio and adjust that amount in subsequent years to match inflation, he in theory would never run out of money for a 30-year planned retirement.

Bella on the other hand, retires a year later (1970) with the same million dollars in purchasing power. Her retirement portfolio is invested just like that of Jason‘s in the stock market.

And she expects to draw the same 4% from her portfolio and inflation-adjust that amount each year for the same 30-year retirement.

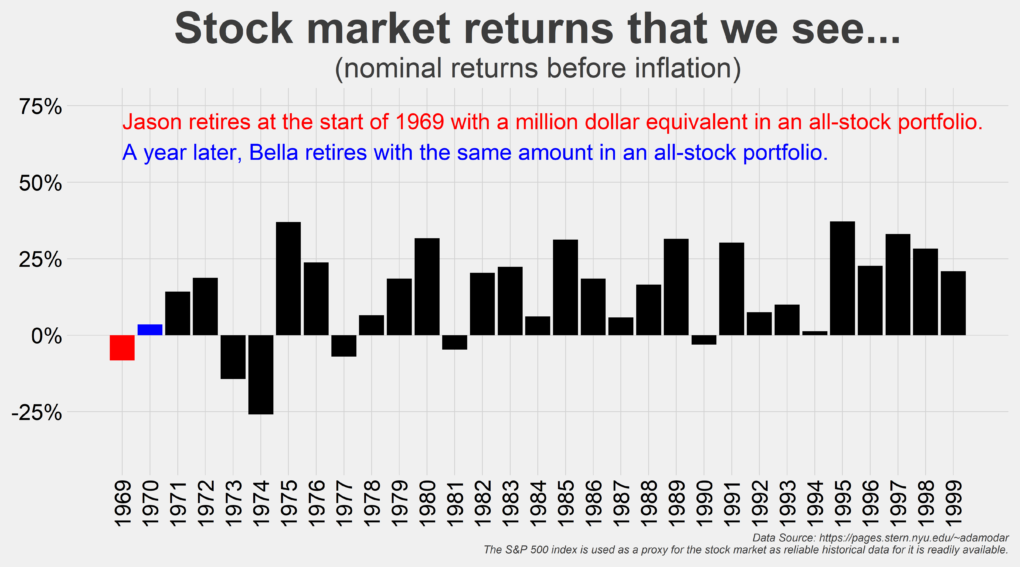

These are the portfolio returns each one of them experience…

Jason‘s retirement starts on January 1, 1969 and ends on December 31, 1998. That is a 30-year span of drawing inflation-adjusted income that we talked about.

Bella retires on January 1, 1970 and is done retiring by December 31, 1999. That again is the same 30-year span of drawing inflation-adjusted income from her portfolio.

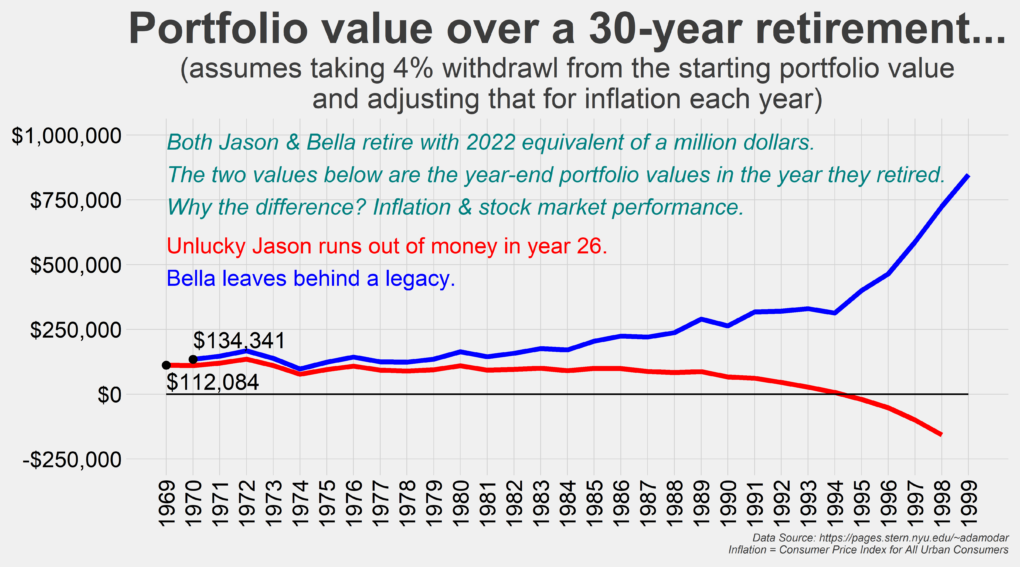

So where is the problem? I mean you don’t expect to see much difference between the two scenarios, right?

But there happens to be a world of difference between the two. Jason exhausts his portfolio in year 26 of his planned 30-year retirement.

Bella on the other hand leaves a sizable legacy behind.

Maybe that was not her goal but the fact that her portfolio is able to deliver on the income she planned while leaving behind that kind of money is striking. And that is just because she retired a year later.

And the money that Bella left behind is in 1999 dollars. If that money remained invested in the same portfolio, it would easily be multiple million today. Not that she gets to care though because she has longed since departed.

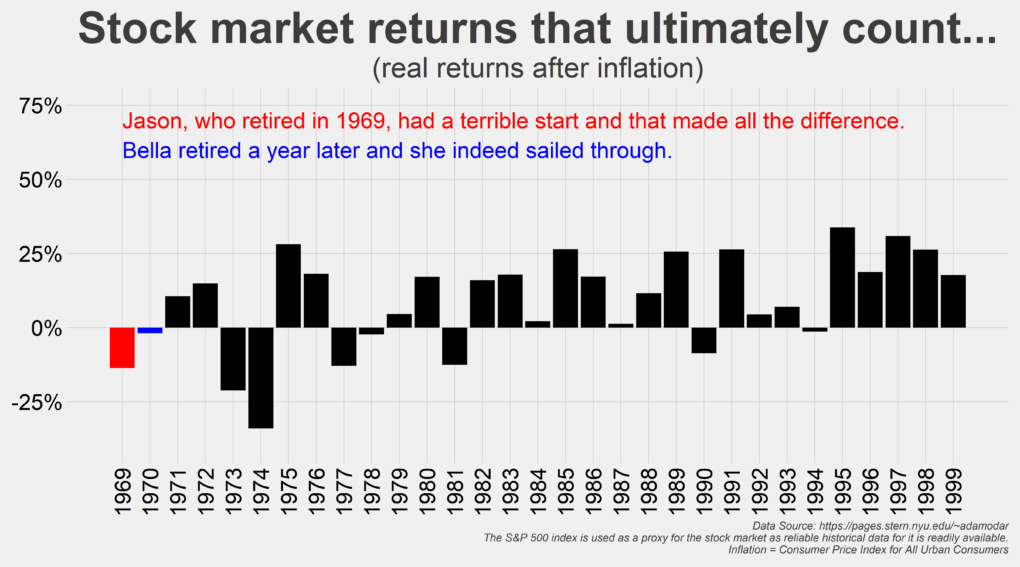

So, what made all that difference? The starting year stock market performance combined with inflation.

The real, after inflation returns for both are as shown below…

Jason‘s money took a big hit right off the gate while Bella‘s didn’t suffer as much. Jason, hence, was drawing income from a smaller portfolio value than that of Bella‘s and that made all the difference.

Some takeaways hence…

- Jason just got unlucky. Out of the 66 periods of 30 years each starting with 1928, there were only five such periods where one would have run out of money following the 4% guideline. And this timeframe accounts for literal world ending depressions and recessions, World Wars and oil embargos, inflationary and deflationary times, bubbles and busts and yet only five such periods. That is not to say that we should be complacent because future market returns could be lower but again, not as dire a situation as I probably made it sound.

- Most retirement portfolios, as one nears the point to start drawing income, would not be holding all stocks. And even if they did, they would or should not be holding stocks in one market, exposed to one type of investment so the chances of a retirement outcome like that of Jason gets even slimmer.

- No living soul that the world knows off will watch the inflation index and adjust his or her spending precisely in line with what the latest numbers show. I talked about this in the retirement spending smile because most normal earthlings won’t spend what they think they’ll spend when they are in the thick of their respective retirements. I am especially talking about the types that got this far reading stuff like this.

- And if leaving behind a chunky legacy is your goal, you might want to ratchet down that safe withdrawal rate from 4% to say 3% of the portfolio’s value. If done right, this money at this new withdrawal rate will last forever and beyond.

But then as life expectancies rise, 30-year retirements might feel short, especially if you retire early. I wouldn’t stress too much but it is good to crunch the numbers every once in a while to make sure you are on track. And a tad bit of conservativeness in your planning never hurts.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Ron Lach, Pexels