Bernard Madoff ran a successful wealth management business for multiple decades. He was the chairperson of the Nasdaq stock exchange. People looked up to him until it was discovered that he was in fact running a giant Ponzi scheme. And the who’s who from Wall Street to Hollywood to Main Street were taken to the cleaners to the tune of sixty-five billion dollars in what amounted to one of the largest frauds ever perpetrated.

So how was Madoff able to pull off a scam this big for such a long time on some of the most sophisticated people and institutions around? The same way Sam Bankman-Fried was able to allegedly swindle billions from some of the most high-profile investors in Silicon Valley. It involved some amount of fear of missing out (FOMO) and a large amount of not doing even basic due diligence.

And unlike the stupid Ponzis we hear about, Madoff‘s scheme was cunningly clever. He promised a steady 10 percent rate of return each year regardless of the market conditions. Outlandish but still believable.

And he marketed exclusivity. You had to be in the know to even have a chance to invest with him.

Now when you have someone manage your money, you’d want a third-party custodian (TD Ameritrade, Fidelity, Altruist) to hold your assets. That custodian then generates all the statements, trade confirmations and the necessary tax paperwork.

That was not the case with Madoff‘s investment management business. Not only was he managing his clients’ money, but he also had custody of their assets, a giant red flag.

So, if you wanted to become his client, you’d open your accounts at Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC, a custodian he ran and controlled. All your investments, which later turned out to be made-up, would be held there. You’d write a check to his firm if you had to move money into your accounts instead of to a third-party custodian.

And because he owned the firm, he was able to forge all the statements and trade confirmations. Investors at his firm thought they were getting rich but that was all on a made-up piece of paper. Investors who entered late were paying for the investors that sold and cashed out their investments until he ran out of new investors to bilk.

So that was the gist of the Madoff scam but dig into any one of the many others we hear about, and they have similar overlapping themes. A few samples below and you do not have to look hard to find them.

Charles owned a company named Infinite Equity Strategies, LLC which he promoted as a financial strategies company that had not “lost a dime in the recession.” Charles held himself out as a financial specialist and safe money advisor, who could help his clients put their retirement funds into products that would provide “high returns without high risk.”

Charles was not registered with the State of Maryland, nor the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser.

Charles told his clients to liquidate their current investments and provide him with the funds, so that he could place the money into safer investment accounts with higher returns. However, Charles instead deposited the funds into his own accounts.

Charles created fraudulent letters and account statements purporting to be from well-known financial products and services providers, in order to lead his clients into believing that he had in fact deposited their money into safe investment products as promised.

Baltimore “Financial Advisor” Pleads Guilty to Defrauding over 22 Clients of $890,000 by The United States Department of Justice, January 26, 2015.

As alleged in the indictment, he falsely told clients and prospects he could guarantee annual returns of 10% on their principal investments, regardless of how volatile the stock market might be, and that he could make an annualized 19.2% return on retirement investments in which clients would also keep their principal.

From February 2014 through November 2021, Lopez received about $19.4 million from clients. But, during the same period, instead of investing mainly in stocks and bonds for clients, Lopez allegedly bought $13.3 million in precious metals, such as gold and silver.

After securing client money, Lopez allegedly generated periodic account statements, “purportedly showing substantial investment gains,” according to the Justice Department.

Arizona ‘Advisor’ Charged With 27 Counts of Mail, Wire Fraud by Jeff Berman writing for Think Advisor, January 9, 2023

Robert Shapiro, the founder of the Woodbridge group of companies, will spend 25 years in prison after pleading guilty to charges that he orchestrated a $1.3 billion real estate Ponzi scheme that bilked thousands of investors out of hundreds of millions of dollars. Nearly two years ago, the Securities and Exchange Commission sued Shapiro for allegedly running a Ponzi scheme that defrauded more than 8,400 investors by promising high returns on real estate investments.

Woodbridge founder Robert Shapiro gets 25 years in prison for $1.3 billion Ponzi scheme by Ben Lane writing for Housing Wire, October 21, 2019.

The ads popped up on social media. Earn as much as 7% interest on your savings by opening an account with a new start-up. In this historically low interest rate environment — when the average savings account pays just 0.09% annual percentage yield — the offer might have sounded too good to be true. Many of the company’s customers are now wondering if indeed it was.

This start-up promised higher interest rates on savings. Now some customers are struggling to get their money back by Lorie Konish, Scott Cohn & Dawn Giel writing for CNBC, October, 28, 2020.

According to court documents, Satish Kumbhani, 36, of Hemal, India, the founder of BitConnect, misled investors about BitConnect’s “Lending Program.” Under this program, Kumbhani and his co-conspirators touted BitConnect’s purported proprietary technology, known as the “BitConnect Trading Bot” and “Volatility Software,” as being able to generate substantial profits and guaranteed returns by using investors’ money to trade on the volatility of cryptocurrency exchange markets. As alleged in the indictment, however, BitConnect operated as a Ponzi scheme by paying earlier BitConnect investors with money from later investors. In total, Kumbhani and his co-conspirators obtained approximately $2.4 billion from investors.

BitConnect Founder Indicted in Global $2.4 Billion Cryptocurrency Scheme by The United States Department of Justice, February 25, 2022.

He is accused of scamming thousands of billions of naira after promising a 25 percent Return on Investment (ROI) monthly.

Baraza: EFCC declares Christ Embassy Pastor Miebi Bribena, wife wanted for ‘N2bn fraud’ by Wale Odunsi for Daily Post, June 10, 2022.

Nutty, who frequently posted dancing and singing videos to her 847,000 YouTube followers, also claimed to be a successful forex trader in her Instagram bio and posted advertisements for private forex trading courses to the platform. She also claimed to be able to deliver major returns to her investors — promising 25% returns on 3-month contracts and 30% returns on 6-month contracts, according to Asian trading site NextShark.

Thai authorities have issued an arrest warrant against a popular YouTuber accused of scamming followers out of $55 million by Mara Leighton writing for Insider, August 31, 2022.

All the victims in this case were promised something that was too good to be true. Those in the Ponzi scheme were all assured a high rate of return in a short amount of time, while the victims of the Bitcoin advance fee scheme were guaranteed above current market value for their Bitcoin. This multi-million dollar case is a reminder for anyone thinking of investing: Be skeptical of any investments with larger than life promises, because if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

Instagram Personality Known as “Jay Mazini” Pleads Guilty to Wire Fraud, Wire Fraud Conspiracy and Money Laundering by The United States Department of Justice, November 2, 2022.

Chavez is the CEO of a company called CryptoFX, which in recent years has solicited money from people in Latino communities to invest in crypto currency in return for potential riches. “We already have more than 20 people becoming millionaires,” Chavez tells his audience in the video. “Over five thousand people …. literally mak[ing] over $500,000 …. And there are many, many, many, many – literally paying off all their debts.”

The SEC suit says Chavez and his company took in money from “unsophisticated investors” and led them to believe they could earn a “90% [profit] in [just] six months.” But – instead of investing that money – the SEC says Chavez and Benvenuto turned around and paid most of it out to previous investors, who were often family and friends. That’s the “Ponzi” payment. The government also alleges that Chavez and Benvenuto also spent investors’ money on themselves, for homes, cars, credit cards, luxury retailers, a hotel residence, travel, restaurants, jewelry, adult entertainment, and a hair salon.

Chicago Latinos Say They Were Lured Into Investing in a Ponzi Scheme by NBC Chicago, January 18, 2023.

I can go on and on but with all these stories, the perpetrators are preying on our innate weakness of not knowing how the financial markets work. And many a times, even the folks perpetrating the scams are clueless.

Some takeaways hence…

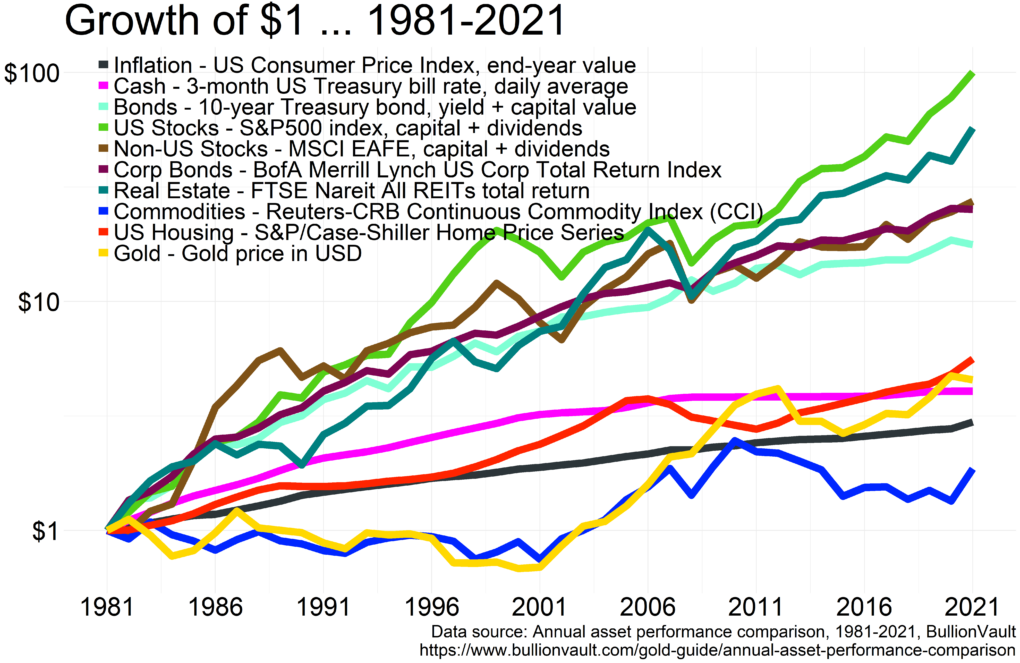

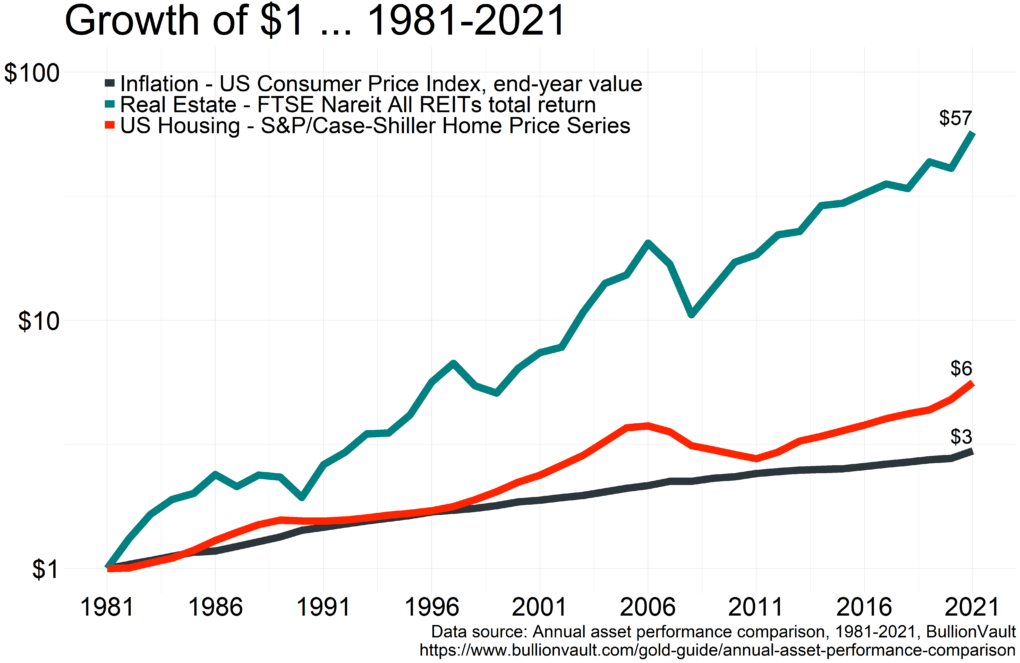

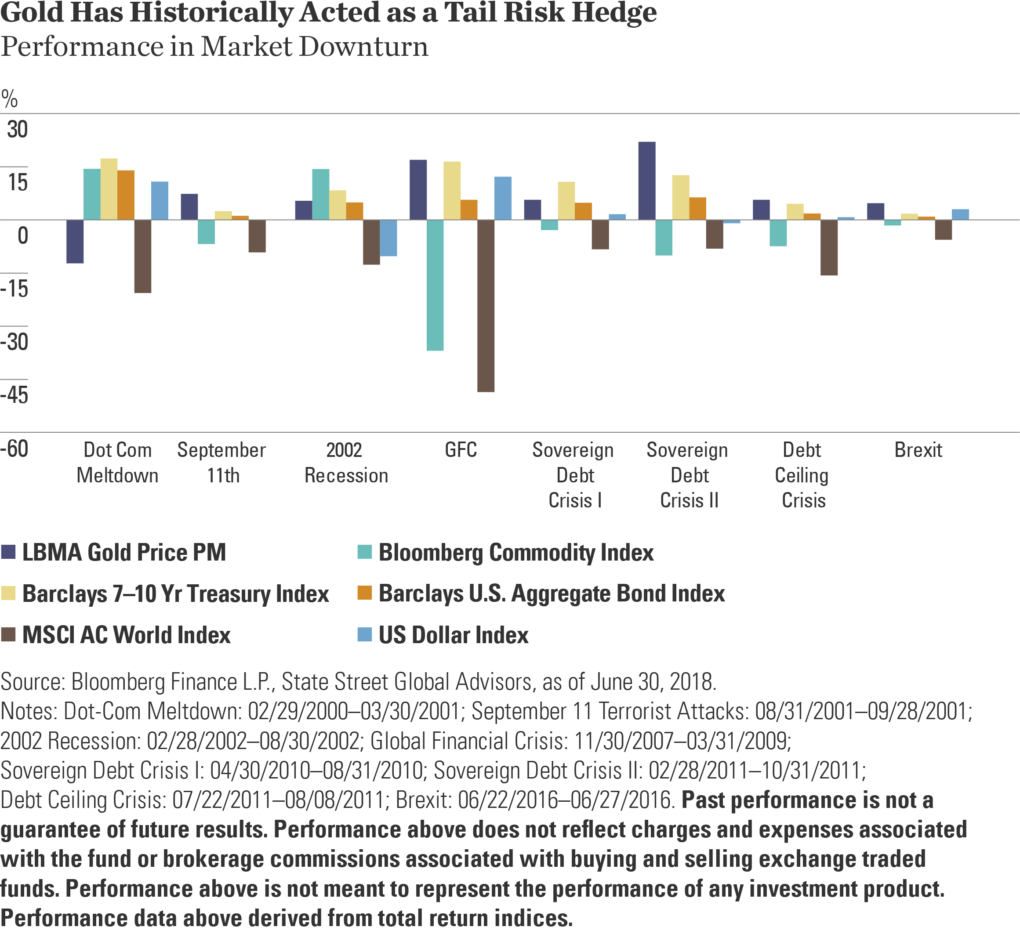

- The 10-year Treasury bond is your go-to baseline when it comes to the safest of all investments. It also aligns with the minimum timeframe you should consider any investment for. Use its yield as a backdrop in making any investment decisions. Anything that yields more than that means there is risk. That is not necessarily an issue as long as you understand those risks. Stocks, for example, should yield more than government bonds because business profits are unpredictable. Interest income from bonds is not. So, with stocks, you want to get compensated for that unpredictability. But there must be underlying profits or interest income or rents (with rental real estate) to call an investment an investment. Do not invest in things that are not investments.

- Investment promises or guarantees of any kind on anything except on government bonds and bank savings accounts is a telltale sign of fraud. Or a sign that you are about to be sold an egregiously expensive insurance product that you should stay away from anyway.

- Stable returns on investments other than, say, on government bonds is also another sign of potential fraud. Don’t care if it is a 3% return or a 10% return but the lack of variance is a giant red flag. Stock market type returns with savings account type stability do not exist.

- The siren song of effortlessly getting rich sounds enticing but it is never real. There is always a catch. If you want to eventually get rich though, a slow meticulous process of steadily acquiring income producing assets is the way. That takes patience and an adherence to the fundamentals of what financial markets can reliably deliver over the long term but anything beyond that and you are asking for it.

- If you don’t know where the yield is coming from, it is coming from you. Stocks pay dividends, bonds pay interest and rental real estate pay rents. Any investment without the prospect of ever generating a yield is investing based on vibes. I do not invest based on vibes and neither should you.

- Your financial advisor should be a fiduciary. Look them up at FINRA to make sure they are registered before even taking that first step. And walk away if they are not.

- Your assets must be held at a third-party custodian. If your financial advisor asks you to move assets to a company he or she controls, run. That is Madoff-proofing your investments to the best extent possible.

- If you don’t know how your money is to be invested, you need to find out. You don’t have to know every itty-bitty detail on the mechanics of investment finance but a basic understanding of the investment strategy being implemented by your advisor is a great start. Ask questions and a lot of them until you are comfortable and confident. That is one reason I write because without that, how will you ever build that conviction to stick around with your plan when the market takes its occasional dumps. You won’t have the conviction, and you will guarantee bail. I write to build that conviction to make sure you never bail.

- Channel your savings to align with the workings of the global economy. Is there an economic value-add to whatever you are investing in? Stocks are ownership stakes in businesses. And businesses form the lynch pin of the global economic engine so they of course must form the base of any financial plan worth its salt. With bonds, you become a lender to businesses and governments. They use your money to do whatever good they are borrowing that money for. With real estate, you provide shelter. These are all value creation endeavors. Anything that is not a value creation endeavor (day trading, forex, crypto, MLMs) is a recipe to lose some or all your money, eventually.

In short, anything that sounds too good to be true, it almost always is.

Unfortunately, for many investors, greed has a funny way of overcoming common sense. Do not let greed swindle you out of your life savings.

Thank you for your time.