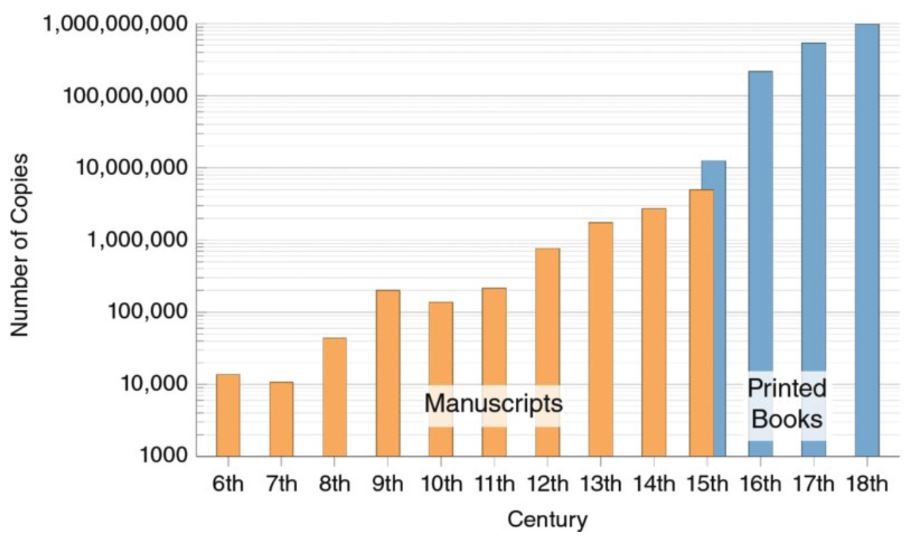

Gary Smith in his book, Standard Deviations talks about the evolution of peppered moths, usually found in nature as light-colored creatures. But that was not always the case.

A trickle of dark-colored moths started appearing in 1848 England but by 1895, ninety-eight percent of the peppered moths found there were dark-colored.

But by the 1950s, the pendulum started to swing back towards light-colored moths, and it swung back to a point that dark colored moths today are so rare that they may in fact go extinct.

So why this back and forth? The evolutionary explanation for that is that the rise of dark-colored moths coincided with the pollution spewing Industrial Revolution. The blackening of trees from soot and smog gave dark-colored moths an ability to camouflage themselves better and hence were less likely to be noticed by predators.

And since they were more likely to survive long enough to reproduce, they came to dominate the gene pool. England’s clean air laws reversed that course as pollution-free trees allowed light-colored moths to blend in better with their environment. That is nature and evolution taking its course with a big help from humans, allowing the fittest and the most adaptive to flourish and thrive.

We are here today because our ancestors, since the hunter-gatherer days, did all they could to fight and survive the many existential threats they faced. Life in those days was short and fragile. The availability of resources like food, clothing and shelter was unreliable. Life shortening hazards lurked everywhere. As a species, our strength lay in our minds. The instincts and the traits that helped our ancestors survive and thrive are still hardwired in us today.

And one of those traits is the fear of an impending loss. We, evolutionarily, are designed to take flight even at the slightest inkling of a loss. That is because when you were living on the edge as what life was like in times past, to lose even a little meant your very existence was at stake.

So quite naturally, the human beings that are with us today are here because their ancestors did everything they could to protect themselves from danger. The gene pool hence is designed with loss aversion as a primary mechanism for survival.

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in their work on Prospect Theory demonstrated that people react differently to positive and negative changes to their status quo. The pain of losing is psychologically twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining, so the theory goes.

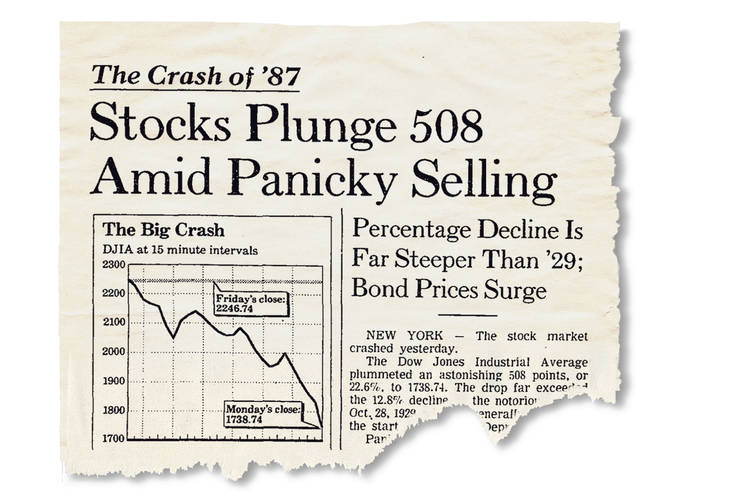

And hence we quiver at the prospect of a headline like this…

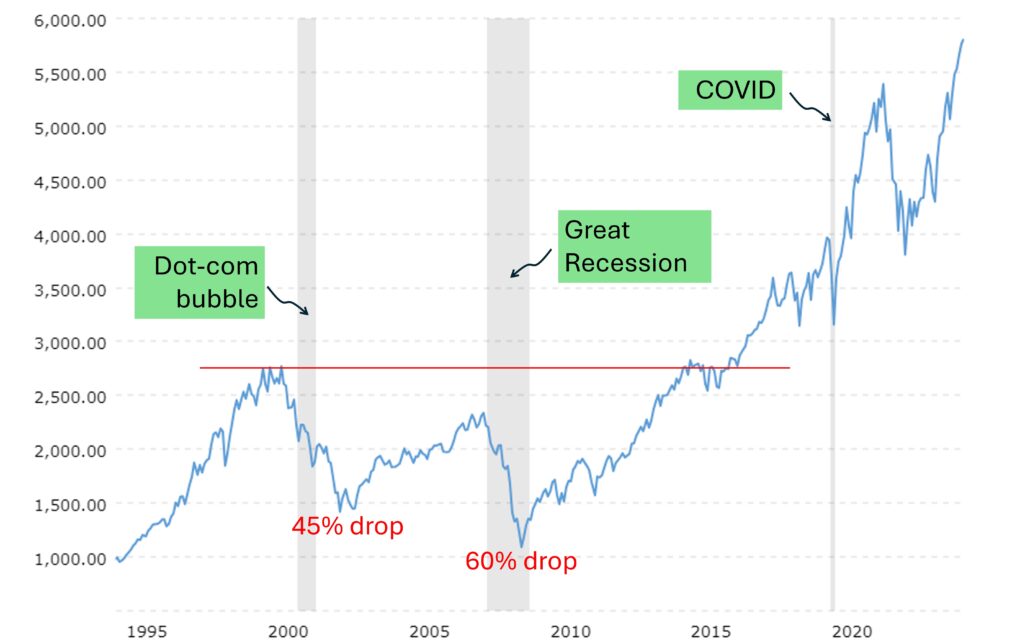

That 508-point drop might appear like a run of the mill drop these days until you realize that that is a 23 percent drop in a single day. But that was in 1987.

The real shocker though is that had you Rip Van Winkled from the start to the end of that year and remained invested, you didn’t feel nothing. The stock market was in fact up for the year.

So, you didn’t lose any money had you not sold. And that is the key thing to remember about stock market downturns. Once you’ve bought right, you don’t have less until you sell.

And what worked for us evolutionarily to survive as a species turns out to be a disaster when applied to our modern-day world of money. It leads us to precisely do the thing we should not be doing and that is to panic sell out of fear of losing all our savings.

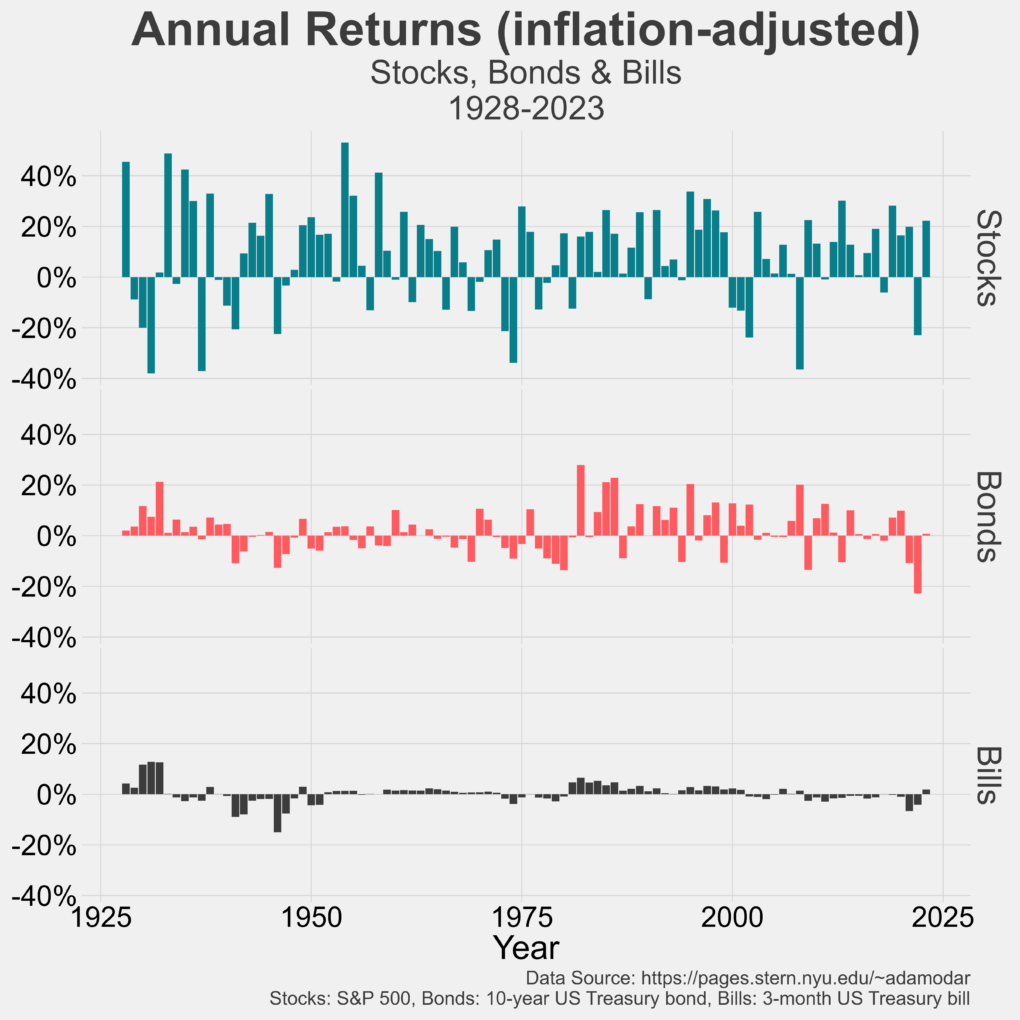

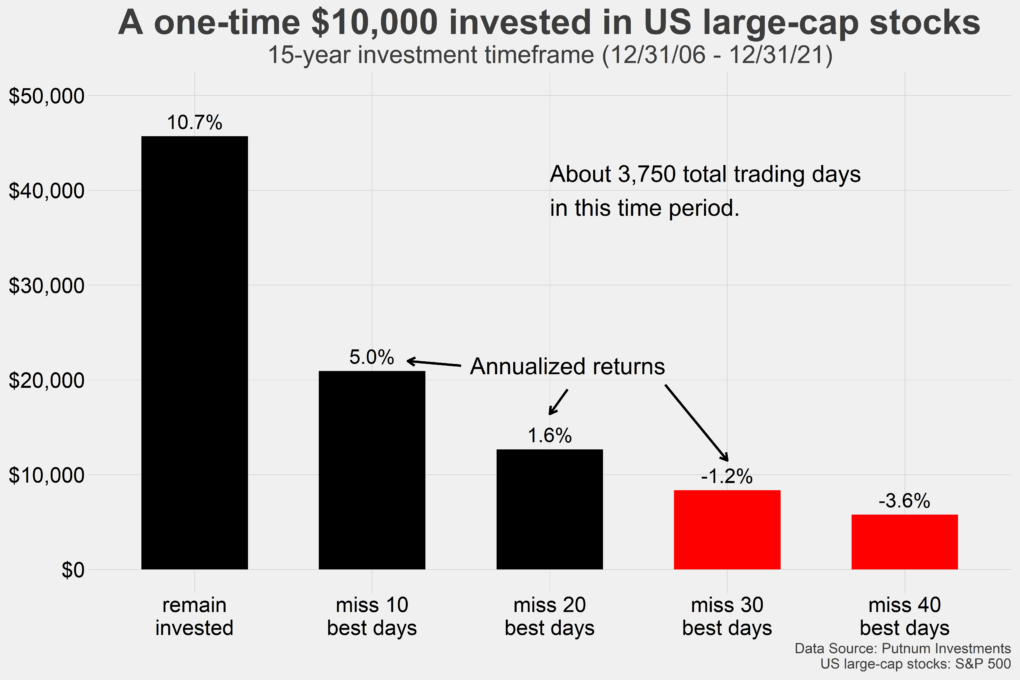

But what if you could dance in and out of the markets to circumvent the pain of a loss? Glad you asked and it doesn’t work. Miss a few of the best days when the markets violently turn, and it is game over.

But can you capitalize on this up and down and then up in the markets? Yes, you can, and you do that by being strategic about how you invest.

Strategic investors are plan-focused on how they deploy their savings. Tactical investors on the other hand invest based on whims. They invest based on what they feel is going to happen next in the markets. Or some try a mix of both as I ultra-sparingly do with my own money just to see what an occasional self-flagellation feels like.

Tactical investors are constantly changing their portfolios. There is no process. They watch every move the markets make. They are always on the hunt for something ‘better’ than what they already own.

Tactical investors feel like they are ‘in the game’. They are making decisions all the time which they think will get them closer to their goals. And it is supposedly fun. It is fun to be ‘in the game’. It is fun to make things happen than it is to let things happen.

And it gives them something to brag about to whoever cares to be bragged about on. They of course only brag about their winners.

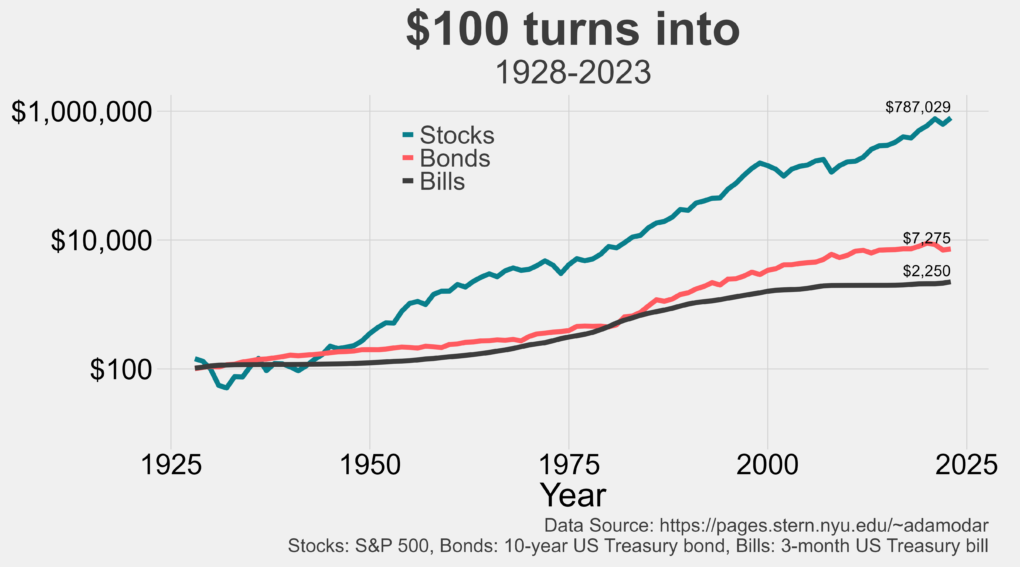

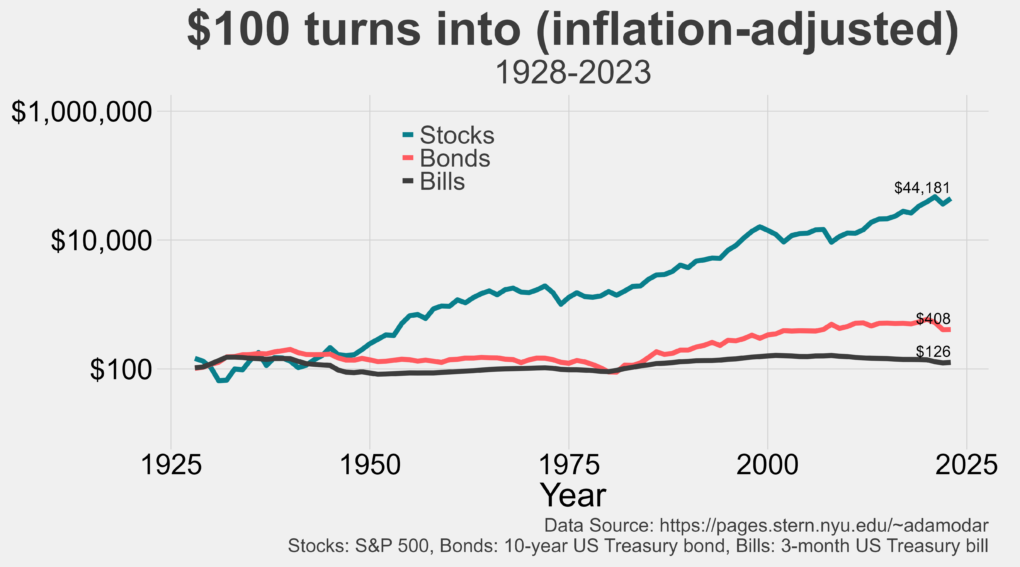

Strategic investors do not play any of those games. They set out with a plan designed around their goals and populate their plans with investments that are statistically likely to get them to meet those goals. They invest like how pension funds invest – matching assets (the investments they own) with liabilities (expenses they’ll incur) to make sure they won’t run out of money before they run out of time.

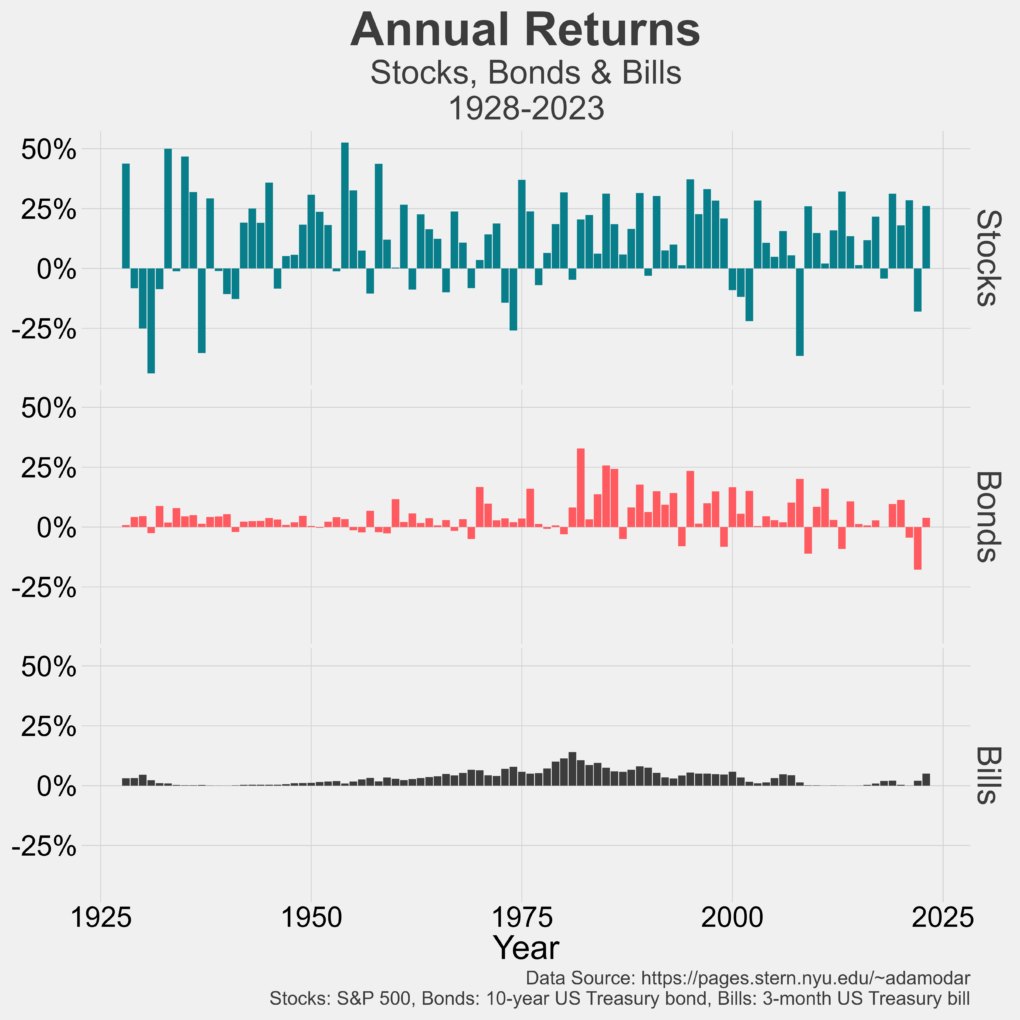

Strategic investors take a long-term, process-oriented approach to investing, centered around prudent asset allocation, opportunistic re-balancing, and tax efficiency.

And most importantly, strategic investors act based on what has already happened whereas tactical investors act in anticipation of what is going to happen. Think about it for a moment. By being strategic, you act based on facts and data. By investing tactically, you act based on hunches. Do you really want to manage your life savings based on hunches?

If you believe in astrology or tarot card reading, you might be more of a tactical investor. For all others, take a strategic approach to managing your savings and sleep easy. Market declines will come and go but you will still have to send your kids to college and plan to retire someday. A solid plan with the right mix of investments with lots of tuning along the way is how you get there.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Cottonbro, Pexels