Up until the late 1800s, horses and buggies ruled the land as the primary mode of short-distance travel. There were innovations and incremental tweaks within that ecosystem with time but nothing transformative. Until Henry Ford came along with the Model-T and disrupted the buggies out of existence.

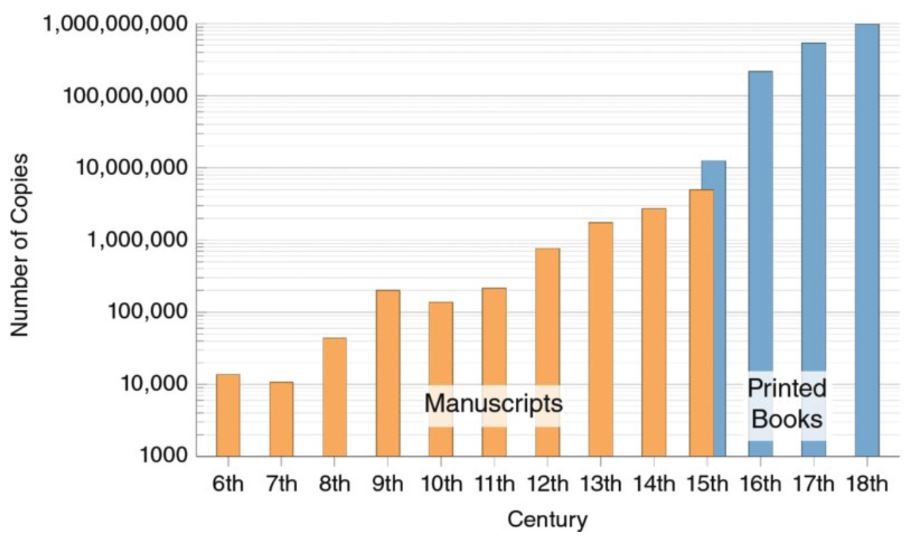

Similarly, Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 1450s drove the manuscript writers out of business. I mean before that, you’d have armies of people literally writing pages by hand, one book at a time, a la the manuscripts.

The invention of the printing press was akin to the disruptive force the modern-day internet brought to the world of information and knowledge dissemination.

And this is what transpired once we could print stuff en masse…

Something similar transpired with the advent of electricity, the light bulb, the telephone, the internet and a million other big and small disruptions that rendered the old way of doing things useless.

Joseph Schumpeter, an Austrian-trained economist, historian, and author called this the process of “creative destruction”. It is capitalism’s way to creatively and systematically destroy the inefficient and reallocate resources to the efficient.

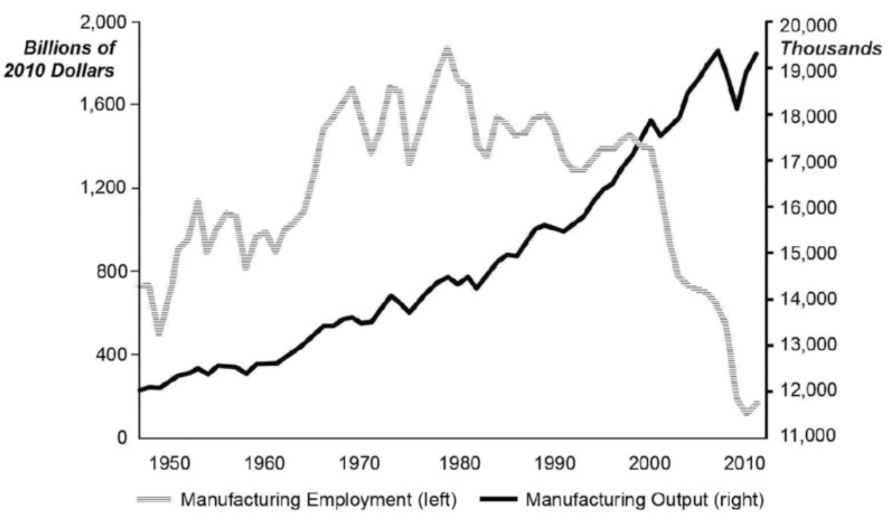

Take manufacturing for example. United Sates is a powerhouse in manufacturing, second only to China and that with a mere ten and a declining percent of its workforce employed in that sector.

Less labor required to produce the same amount of stuff is in fact a great thing except for the ones losing their livelihoods in that process.

So, there is definitely a need for a robust social safety net that catches these people when they fall, retrains them if need be and then sends them back out into the workforce to do their life’s work. And I have come around on this from so far back that you wouldn’t want to believe it but then if you can’t update your priors in light of new evidence, what good is it to exist as a thinking, compassionate human being.

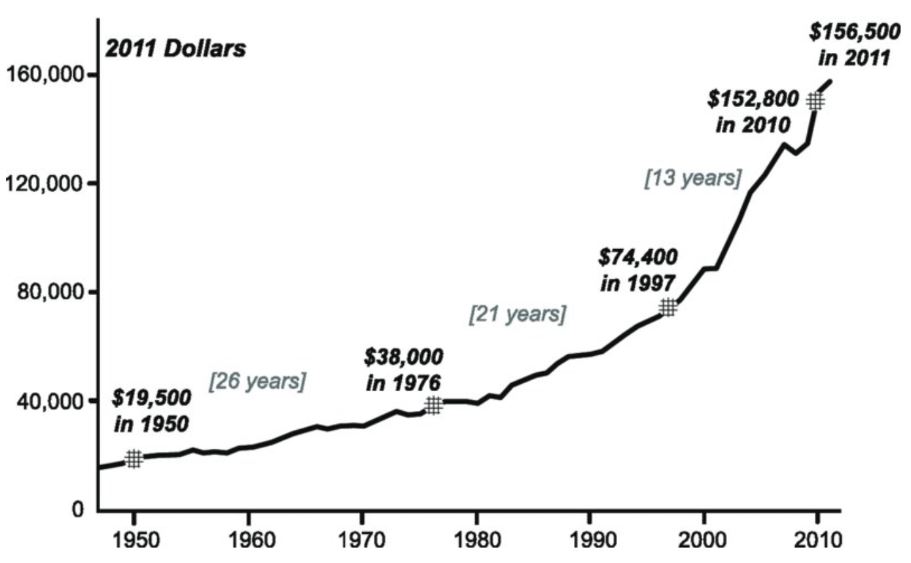

But back to this, wealth creation and the ensuing prosperity in an economy is mostly about productivity growth. And where capitalism’s forces of creative destruction remain unleashed, productivity growth follows.

And a big component of that growth of course translates into rising values of businesses, both public and private that we get to partake in. The benefits though, accrue to everyone, not just the stockholders.

It might not appear to us as to how good we have it so let me take you back to the good old days of the early 1900s, the times when John D. Rockefeller was the richest person around. Yet he had no TV, no internet, no air-conditioning, no airplane travel for most of his life, no mobile phones, not even penicillin1. For the richest person around.

Or take Calvin Coolidge, the 30th President of the United States who served during the 1920s and whose son died due to an infection caused by blisters that he developed while playing tennis, an implausible likelihood these days for literally anyone, anywhere1.

Or take Maria Theresa, head of the entire Habsburg empire for 40 years in the 1700s who saw six of her 16 children die before reaching adulthood2, an unheard of ratio for any parent these days including the ones born in some of the poorest regions of our planet.

Life is so good yet the reason most of us feel inadequate is because we compare and contrast, especially when it comes to money. And then we get sad. It is hard to find perspective but find we must. Each one of us is way richer than we think we are.

But back to capitalism’s creative destruction, its forces are alive in our portfolios as well. And what better way to show that than by taking you back again to the big bad days of 1960s world of stock portfolios where if you didn’t own Xerox, you were a loser. If you didn’t own GE, I mean The General Electric, you didn’t know what you were doing. Same for IBM, Eastman Kodak, Polaroid and on and on.

We know the Dow Jones Industrial Average or as they say the Dow, an oft-quoted stock market benchmark that though flawed with just 30 components, has in fact proved to be a remarkably good barometer for the nation’s economic health. Yes, stock markets are not everything yet in a way they are.

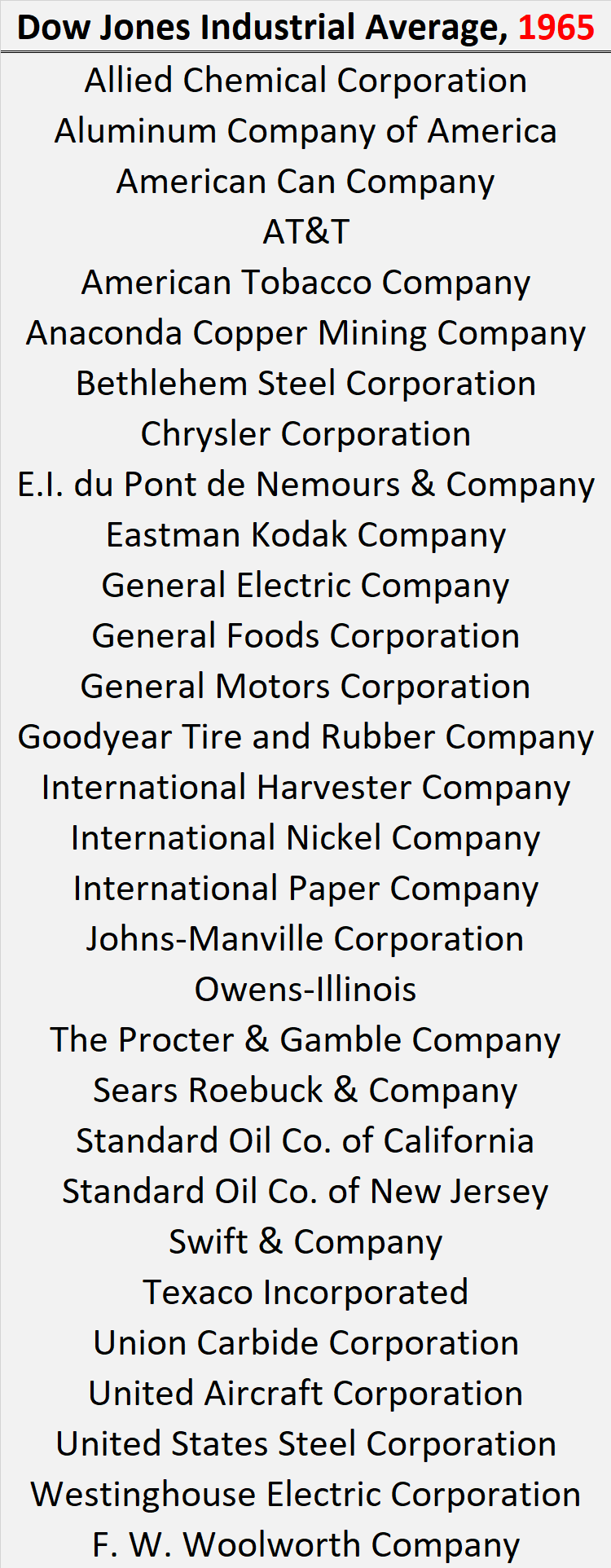

So, imagine you are sitting in 1965 trying to build a portfolio to deploy your life savings into and of course, you would be looking for the bluest of the blue chips. And what better way to populate your portfolio with than to just buy what the Dow owns.

And this is what it owned…

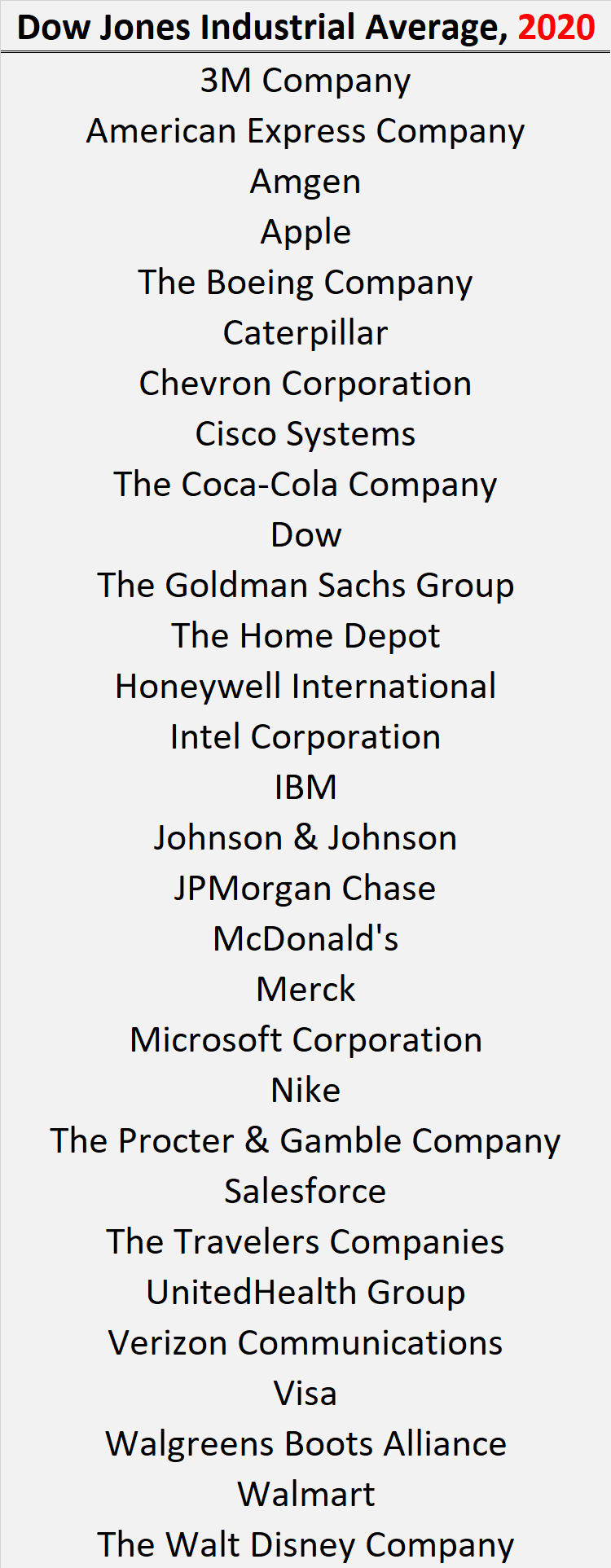

But then Schumpeter‘s forces of creative destruction did their work, and this is what that same Dow owns these days.

If you held onto the businesses of 1965 beyond their useful life and made no changes, you wouldn’t be sitting pretty.

And yet, a single $10,000 invested in 1965 in this comparatively dumb Dow would be $2.5 million today. Even with all this creative destruction taken into account because the Dow kept on evolving as the economy evolved.

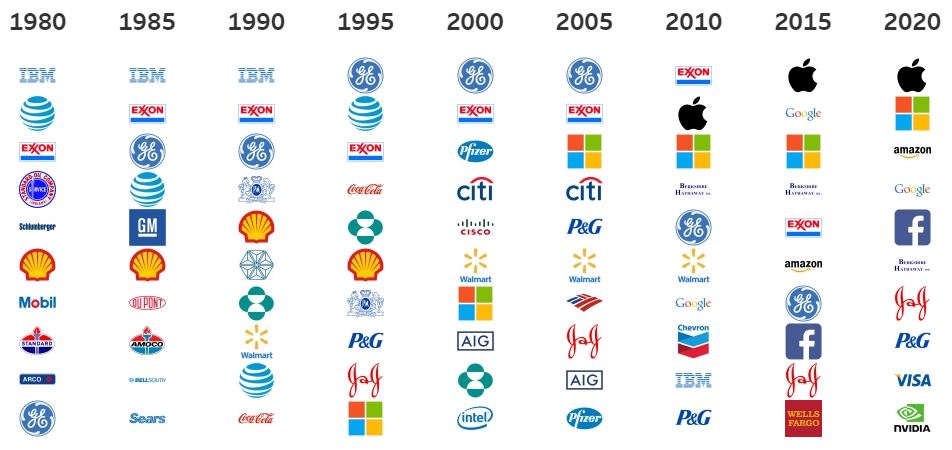

John VanGavree, an analyst working for the U.S. State Department put together a dashboard that highlights the changes in the top 10 holdings in the S&P 500 index in five-year increments. And even in such a short period of time, its components change and sometimes, dramatically.

And it is natural though. Large companies become slow, bureaucratic, and difficult to navigate or tolerate for employees who want to break things. In a good way though.

So, they leave, picking up venture capital on their way out and starting new disruptive businesses.

So too top-heavy a portfolio adds this extra layer of large-company disruption risk that can be designed around.

Plus, data going back to 1970s show that companies that finished in the global top 10 in terms of market value have had less than one in five chance of finishing the next decade there.

And in the decade after companies reach the top 10, they typically see earnings growth fall and profitability decline. Returns of course always follow so they end up giving back all the excess gains they made in their run up to the top3.

Competition and churn lie at the heart of a functioning capitalist system. That is why the giants of one decade so often deliver such underwhelming returns in the next one, and shrink in the popular imagination. Expect that pattern to recur unless capitalism is truly broken.

“How the US tech giants could fall” by Ruchir Sharma, Financial Times, August 15, 2021

Plus, competition and disruption is happening at a pace never seen before. There is no way to tell if what you own today will occupy the same space even a year from now, forget a decade.

So, with all these, a few takeaways…

- The darlings of today may appear invincible. They always do. But unless capitalism is truly broken, they will be replaced. They must be. So, if your portfolio is overly concentrated, you must plan to un-concentrate before it’s too late.

- And the fact they are the darlings today means everyone knows about them. And when everyone knows about them, everyone wants to own a piece of them. So, more demand with the same supply means price inflation that you pay for when acquiring popular businesses. Yes, markets are supposed to be efficient, but they seldom are in the short term.

- And you might be unknowingly over-concentrated in some of the top names with no fault of your own. Maybe you work for one of these outfits and acquired shares through employee plans over time. As much as you hate letting some of your shares go, let go you must because history is not on your side. The way to do it is to slowly trickle out of them the way you trickled into them. Sell at a set schedule and don’t look back.

- And last, build a portfolio where you get to participate in the rise in the value of a business from small to mid and from mid to large. That is an extra value capture that you can avail of through portfolio tilts you can apply towards mid and small size businesses. Some will complete the full cycle from small to mid and from mid to large and eventually to extinction. Others might merge or get acquired halfway through that process and some will flameout prematurely. But owning a broad enough basket of them spread across the size spectrum means you’ll get to turbo-charge all that capitalism has to offer.

Thank you for your time as always.

1 David Henderson. “Richer than Rockefeller“, Econlib. February 8, 2018.

2 Laura Vanderkam. “All the money in the world“.

3 Ruchir Sharma. “How the US tech giants could fall“, Financial Times. August 15, 2021.

Cover image credit – Smithsonian Institution