Rule number one – don’t lose money. Rule number two – don’t forget rule number one. That of course is classic Buffett.

So, say you have a choice between investing in the hottest tech stock around or in a basket of stocks that represent say the entire tech sector. Which one do you think offers a better risk-reward situation? A basket of tech stocks of course.

Prices of investments moving up or down, even violently at times, is not risk. The likelihood of losing purchasing power over time is the true risk. The fortunes of a single business can decline and never recover but the fortunes of an entire sector, rare but it could still happen.

Like say you invest in a fund that owns a basket of oil company stocks and you think that is safe because you are technically diversified across many businesses. But you are still making a sectoral bet. Can you predict that sector’s profits twenty years from today?

Not so easy because it is quite possible that the entire sector could be disrupted out of existence or at the very least, prominence due to advances in technology.

So, there is a non-zero probability of loss by investing for the long-term in a supposedly diversified investment.

But what about investing in all sectors of an economy through an investment that represents say 500 of the largest publicly traded businesses in these United States? That is the S&P 500 index that we are all familiar with.

So, we are now getting to a point where we have diversified away any diversifiable risk associated with a single company or a sector in a given economy.

But then there are still gaps as S&P 500 is a collection of 500 large publicly traded businesses in a single country. Then there are mid-size companies, small companies, international and emerging market companies. And then there are domestic bonds, international bonds, real estate and so on.

Talk about S&P 500, back in the Dot-com days of the late 1990s, the S&P 500 then, just like these days1, was extremely top-heavy and concentrated. The top 10 companies made up more than 30 percent of its total value.

Where is the problem? The problem is that this happens when investors come to believe that stocks of some businesses are better (and safer) because they have a great story to tell. They are the stocks everyone owns. They are the stocks everyone talks about. They are the stocks everyone loves.

But investing for the long-term isn’t a popularity contest. The investments that everyone is chasing are usually overhyped and overpriced, with prices driven higher not so much by fundamentals but because more and more investors are piling into them.

And when the valuation pendulum eventually swings, you get left holding the proverbial bag, sometimes forever, because you paid through the nose for those agreeably wonderful businesses. The businesses themselves may not be the problem. The price you pay for them is.

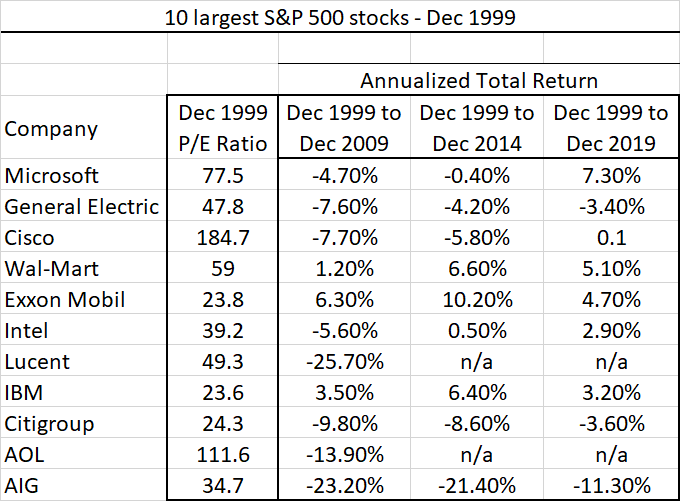

This below is the performance of the top ten largest stocks in the S&P 500 index back then (late 1990s) to twenty years later.

n/a = bankrupt

The only one that turned out respectably okay was Microsoft. But that was after holding on for 15 years to surpass its prior peak reached during the Dot-com times.

Cisco Systems has yet to reach the highs set 25 years ago. Same or worse stories with the rest.

And it is not like these businesses don’t make money. Cisco, for example, is a cash generating machine. It dominates its markets. It is just that investors paid too dear a price for a very popular investment of the time and the profits have yet to catch up to that price.

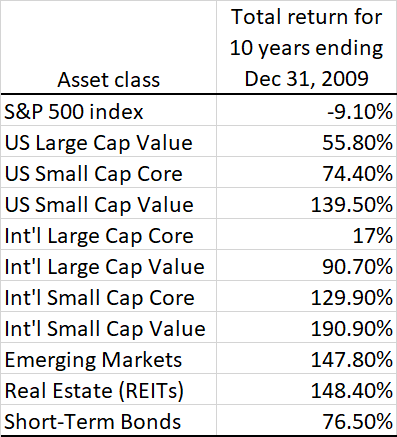

But back to S&P 500 and since that index was so concentrated, it quite naturally took a beating when the Dot-com bubble burst. And that showed up in that index’s subsequent 10-year performance…

So, if you just owned the S&P 500, you had a problem. Not a big problem if you had the wherewithal to stay invested but that is easier said than done.

And most investors won’t because to persevere through a decade long underperformance, you’d have to approach portfolio construction from a much deeper perspective than many do.

But back to overconcentrating in a single stock or a sector risk, you better be super lucky and choose right. Because choosing wrong, which is more likely, can upend your life.

There is this WSJ story that I often cite when explaining concentration risk. It talks about how workers at General Electric loaded up on their employer stock during their tenure to a point where many had pretty much their entire life savings tied up in this one stock.

Now imagine telling someone to diversify out of GE, the bluest of the blue chips that has been around for more than a century, a business that has survived Worlds Wars, recessions and depressions, a business that is the only surviving member of the original Dow Jones Industrial Average.

And who could have predicted that a diversified conglomerate like GE with market leadership in industries ranging from jet engines to medical equipment to financial services could fall on hard times. The consequences for the employee-stockholders though were brutal…

You had a job for life if you had gotten in there,” said Mr. Zabroski, 61 years old. He rose to punch-press operator and retired in 2016, after working 40 years at the century-old plant, which roared to life during World War II and still churns out engines for jets and helicopters. He left GE with an annual pension of $85,000 and company stock valued at more than $280,000.

Retirement looked pretty good until GE shares collapsed. His shares are now worth about $110,000, prompting a late-life job hunt. “I never planned on retiring and having to go back to work,” said Mr. Zabroski, who has monthly mortgage payments and supports a partially disabled wife. “It’s kind of scary.”

Mr. Zabroski’s situation doesn’t appear as dire considering his $85,000 a year pension but then that is at risk as well if the company continues to flounder.

Among those hard hit by GE stock losses have been company retirees, including former factory workers who took advantage of a stock-ownership plan to build their savings. For decades, the company has had a program that encourages employees to buy GE shares by offering to match 50% of worker contributions, which were taken directly from paychecks.

With 71.4% of assets needed to cover its pension liabilities, GE is one of the worst funded large corporate pension plans in the U.S., according to an April report by consulting firm Milliman Inc. GE’s pension obligations, nearly $100 billion at the end of 2017, are underfunded by almost $30 billion.

Mr. Marruffo‘s situation isn’t looking that hot either as he too loaded up on GE stock…

Mr. Marruffo, 71, started with GE as an apprentice, working in different engineering and manufacturing areas. Just like many business experts, he respected GE’s management. Mr. Marruffo accumulated GE stock through the company’s Savings and Security Plan. He figured the company was just about invincible, which made the fall in its stock price devastating. He sold some last year but still owns about 6,000 shares. He now regrets he didn’t sell more.

Employees need to think very carefully about investing their own money beyond 10% in company stock,” said Corey Rosen, founder of the National Center for Employee Ownership, a nonprofit that works with companies. “If you are looking at retirement, then diversification is a good thing.”

Getting folks to diversify out of their employer stock is never an easy discussion, especially when it relates to some of the hottest stocks around. Plus, as an employee-stockholder, you want to believe in the future of your company so much that it is hard to bring yourself to let go of your shares.

But let go you must because the business landscape is strewn with past darlings that could do no wrong that are now just a shell of their former shelves. Some don’t even exist anymore.

Take Yahoo, for example. It had a peak market value exceeding $100 billion at one point but fifteen long years later, it got sold to Verizon for a mere $5 billion. Then there are the former stalwart businesses like Sun Microsystems, AOL, JDS Uniphase, Palm, and others from the Dot-com times that have completely vanished.

Go back in time even more and you find the Xeroxes and the Kodaks and the Polaroids of the world. Those were the Googles of their times that don’t exist anymore.

So, what do you do if you find yourself in that lucky situation of holding too much of a good thing? Do you sell all at once? Because the moment you sell, you know what is going to happen next. The stock is going to shoot up like a rocket.

So instead, I say you scale out over time just like how you scaled in. Pick a date and a timeframe and sell and keep selling until you are done.

Carl Richards in his book The Behavior Gap talks about a conversation you should be having with yourself if you have a majority of your net worth tied up in a single stock or a sector.

A guy I know had his money invested in his company’s stock. He had enough money to retire comfortably, but he believed there was a good chance the value of the stock could continue to rise – maybe even double. He wanted to know if he should sell the stock upon retirement, or hang on and wait for the stock to go up further.

We had the Overconfidence Conversation.

I asked him three questions and we answered them together.

Question one: What happens if you hold the stock and you’re right – the stock doubles?

Answer: You’ll have more money.

Question two: What if you hold the stock and you’re wrong?

Answer: You’re going back to work – maybe for twenty years.

Question three: Have you been wrong before?

Answer: Yes.

He sold the stock.

It is hard enough to get rich once. Don’t force yourself to get rich twice.

If you are already rich, there is no upside to taking on a lot more risk, but there is disgrace on the downside.

Warren Buffett

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Sander van der Wel, Flickr

1 December 31, 2019