Whether you like it or not, the stock and bond markets is where a bulk of your savings will end up. Or at least they should.

Owning stocks means owning pieces of businesses while owning bonds means becoming a lender to the same businesses or sometimes to the governments.

In case a business goes bankrupt, the bondholders get paid first before the stockholders get anything. But in exchange for that apparent safety, you give up on returns. A lot of returns.

Interest payments on bonds are fixed and hence more predictable than dividends from stocks, another reason for the lower perceived risk with bonds than with stocks. And lower perceived risk means lower expected returns.

The price of a stock depends upon the level of current or expected future dividends and with dividends being volatile means stock prices will be volatile.

Dividends from small company stocks are more unreliable than from large company stocks. Small company stocks, hence, are expected to be more volatile (riskier). More risk should mean more return but let’s see.

I’ve got monthly returns data for three categories of investments starting back in January of 1987.

- Bonds: And specifically, long-term Treasury bonds. By buying them, you are lending money to the Federal government for a 10-plus year timeframe. And since the Federal government cannot go bankrupt, this is as risk-free of an investment as it can get assuming you hold on to them for the entirety of the term.

- LargeCapStocks: By owning these, you own stakes in some of the biggest businesses in America.

- SmallCapStocks: These businesses are nimble. They can grow fast. They can also fail easily. The risk is high, and you want to get compensated for that risk. So, the expected returns should be high. Or they are supposed to be high. Finance textbooks tell us that.

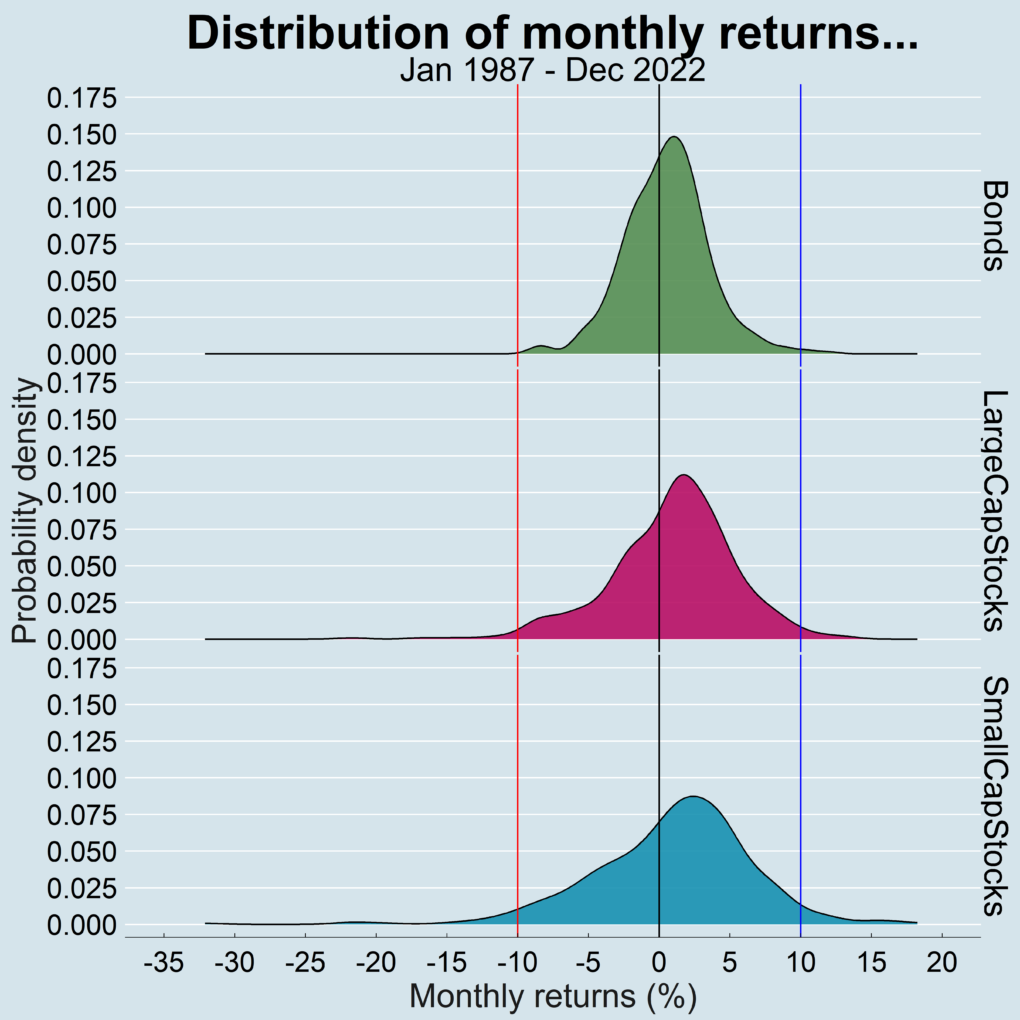

And this is how the three investments behaved.

Probability density tells us the proportion of months out of the total months where returns varied between any two ranges. Take the sub-plot for bonds for example. We can roughly state by eyeballing it that for about 60 percent of the months, the monthly returns were between zero and 10 percent. In fact, we can make that claim for all three categories of investments.

I show three vertical lines for each sub-plot; at zero percent in black, at -10 percent in red and at +10 percent in blue. Some observations…

- You know that if you bought and held any of these investments from the start of the period to the end, you made money. And in some cases, a good chunk of money. How do we know that without doing more number-crunching? By eyeballing the area under the curves for each investment that fall to the right of the black dividing line at zero percent. The area under the curve for each one of them is greater to the right of that line than to the left. That means that at any given time, on average and if you held on, your returns were more positive than negative and that compounded over months and years is what gets you to that good chunk of money.

- As you go down the plot from bonds to small cap stocks, the distribution of returns gets wider and flatter. Bonds have the tightest distribution, small cap stocks have the widest, flattest distribution. What does that mean? An increasing level of volatility as the distribution gets flatter. Some use volatility and risk interchangeably but volatility is not really risk as broad-based asset classes don’t go to zero. That is not true with individual stocks and bonds. Bonds have the tightest distribution which in statistical terms means the smallest standard deviation (volatility). Small cap stocks on the other hand have the highest standard deviation and hence are considerably more volatile than bonds.

- It’s not as apparent but if you were to observe the peaks to the right of the zero-marker black line in each sub-plot, the peaks drift a little farther away from that line for stocks as compared to that for bonds. That implies that on average, monthly returns for stocks were higher than for bonds. Again, nothing pathbreaking, just one more observation.

Most mistakes happen in the tails…

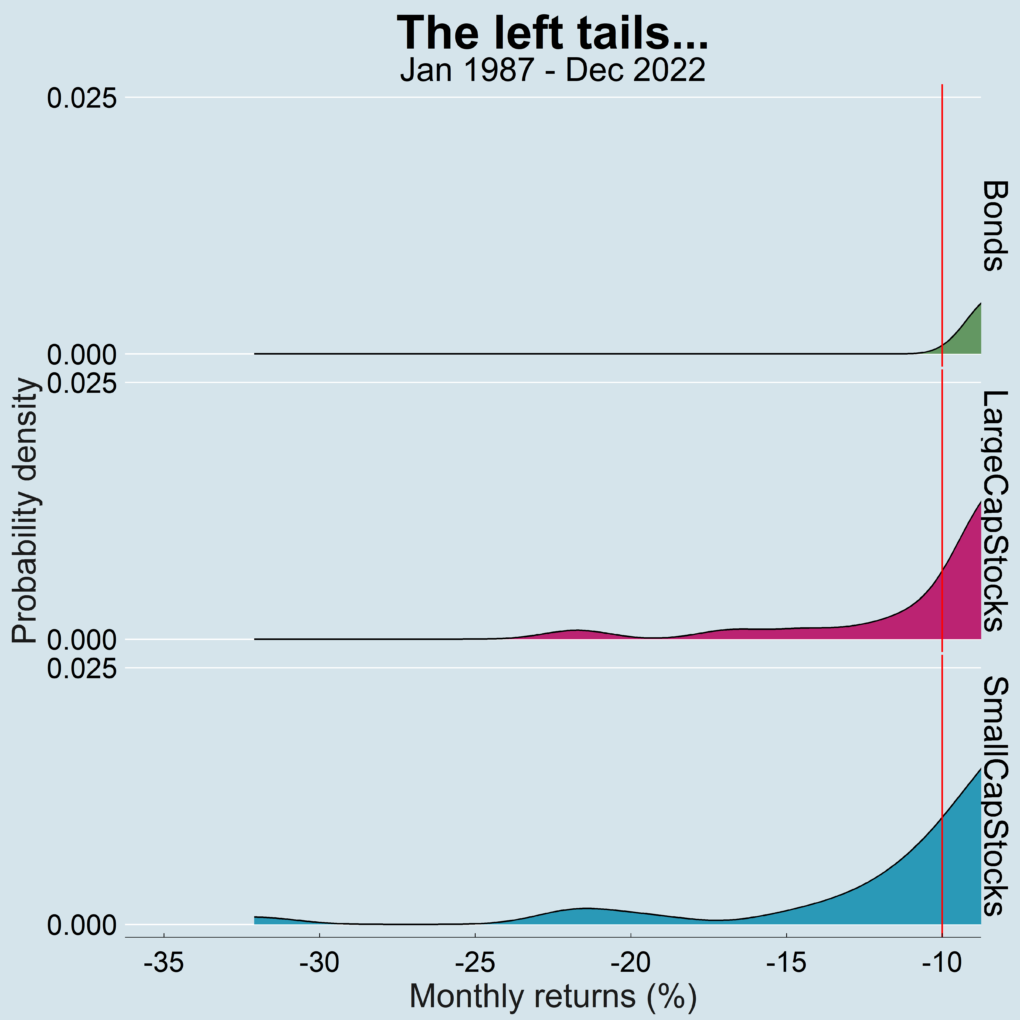

Then there are those long tails and specifically the left tails below -10 percent which are sort of visible for stocks but not very clear for bonds. So, zooming in…

Bonds had virtually no instances where you endured a monthly decline of more than of 10 percent.

That is not true for stocks. Of all the months (432 in total), you’d have to endure monthly decline of more than 10 percent for large cap stocks six separate times. That is 1.4 percent of the total months.

The worst monthly decline for large cap stocks was -22% in the year 1987. For those who know their history, that month includes the ominously called Black Monday. The rest of the “bad” months coincided with major market panics brought about by the Asian financial crisis, the Dot-com tech crash, the banking crisis of 2008 and of course, the Covid pandemic.

And these “bad” events are what forms the left-tail in the plots above. And that is where the gravest of all mistakes happen. No one panic sells during the right-tail months, also considered the “good” months.

But if you have a plan and a conviction to act, the “bad” months in fact are the best months to invest new money. And the “good” months naturally are the worst. You are buying future cash flows (dividends). You should be euphoric when you get to buy the same amount of cash flows at 20 and 30 percent discounts.

Bull markets begin with the feeling that the market can only go lower. Bear markets begin with the feeling that the market can only go higher.

Peter Atwater

Back to the data, things get a bit wilder with small company stocks where you’d have to endure 14 separate monthly declines of more than 10 percent. That is more than double the number of months for large cap stocks. There was even a month in the year 1987 where small company stocks declined a horrid 32 percent. In a single month. Imagine waking up a month later with a third less of your money?

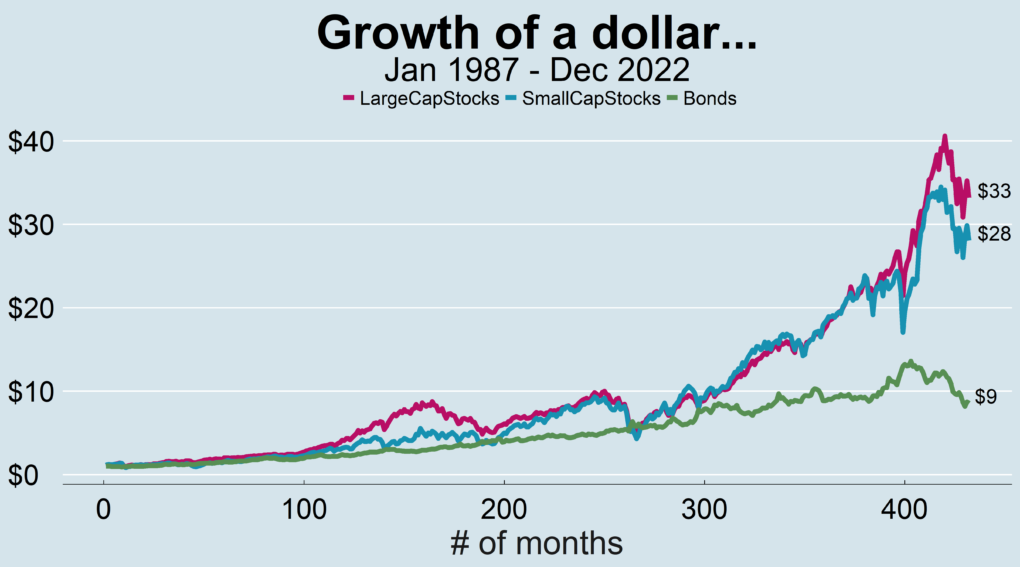

The natural question then is that you’d have made more money investing in small cap stocks, right?

Hmmm no. You made more money in stocks than bonds in general and that was expected. But you made less money in small cap stocks than in large cap stocks. Even after taking all that risk. Isn’t that interesting?

The game of investing is interesting. Does that mean we ignore small cap stocks? No. What that means is that we don’t know what will do when in what cycle. And we don’t know when those cycles turn. We just have to wait for them to turn.

This discussion as always comes down to the process. If you have the right process defined around a solid, theoretically grounded investment plan, you just have to accept the occasional vicissitudes in the markets and invest away.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Anete Lusina, Pexels