Tim Urban in one of his posts, The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence, attempts to measure the accelerating rate of human progress through something called the Death Progress Units (DPU). Take George Washington for example, our first president and likely a very curious dude from the mid-eighteenth century and say we transport him to today.

But imagine his times. There was no electricity. There was no running water. Transportation was a horse. Long distance communication meant that either you’d use smoke signals, fire a cannonball, or send a letter through a horse carrier.

But today, he sees metal cans whizzing by on freeways at speeds incomprehensible to him during his times. You show him the airplane. That he could be anywhere in the world in less than a day. You tell him about the International Space Station. You show him the internet. The iPhone. That you can make video calls and talk to anyone, anywhere across the globe. You play him music that was recorded 50 years ago. Flabbergasted would be the least of what you would expect him to be. He would die of shock seeing all this progress.

Now take Leonardo da Vinci who lived in the 1500s and say we transport him to George Washington’s times in the 1750s. What does he see? Just like in his times, there is no electricity. There is no running water. People still commute by horse. And the same set of communication devices exist. Some improvements here and there but not much change.

And certainly not at a scale that would kill him of shock. One would have to go back 1000s of years to see a big difference.

So how far into the future one must go to literally die of shock watching the scale of progress. That is what Tim Urban means by DPUs.

And 250 years in the grand scheme of things is nothing. It is a recent, recent history like yesterday. Yet, look at the world today compared to the world just a few centuries ago. The difference is night and day.

And DPUs are getting shorter and shorter…so short that we could witness that level of progress in one lifetime like what could take George Washington 250 years to witness.

This pattern—human progress moving quicker and quicker as time goes on—is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls human history’s Law of Accelerating Returns. This happens because more advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies—because they’re more advanced. 19th century humanity knew more and had better technology than 15th century humanity, so it’s no surprise that humanity made far more advances in the 19th century than in the 15th century—15th century humanity was no match for 19th century humanity.

Tim Urban

So, progress is happening at a faster and faster rate due to the compounding nature of knowledge.

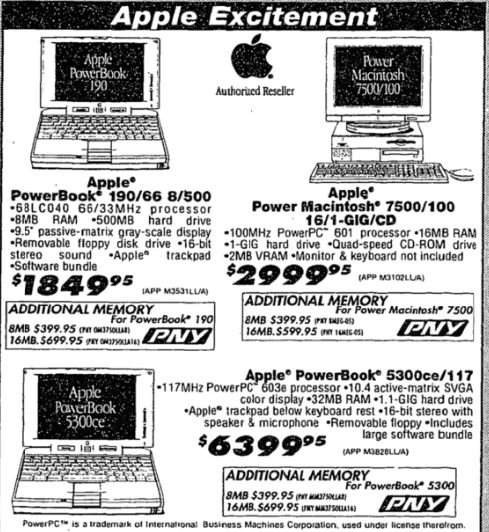

The computing revolution is another example where we observe compound growth in real-time. We started off with vacuum tubes and look at where we are today. This ad for Apple products from the bad old days of 1995 is exhibit A signifying the scale of progress. And this was the cutting edge then.

Do not miss out on the $6,400 in 1995 dollars for a laptop with 32MB of RAM – less than a thousandth of what we’ll find in the cheapest of phones today.

And assuming customers flocked to the stores to buy these products meant that Apple as a company made profits. And say that was a 100 million dollars in 1995.

Apple was a public company then, so those profits belonged to the shareholders. Apple had some decisions to make with that money…

- Distribute 100% of it back to the shareholders in the form of dividends.

- Distribute some as dividends and use what remains for reinvesting in research and product development.

- Retain all profits with none going to the shareholders…for now.

Clearly option 1 would have been a disaster for the company as well as for the shareholders as none of the profits would have been used to build the next set of products that made Apple what it is today.

And of course, a disaster for their customers as well. Imagine life without a smartphone

Option 2 would have depended on what rate of return the company could generate by reinvesting the profits back into their business. And the fact that the company didn’t start issuing dividends until recently proves that Apple’s management had better use for the money. Option 3 hence is what they chose.

And that clearly proved to be the right call as we all got to see. At least in theory, it was the right call, not discounting the fact that they almost went bankrupt until Steve Jobs orchestrated the kind of turnaround that’ll probably be the recorded best in business history.

But that is the nature of the game. No business embarks on a project with the intent of losing money. They will make mistakes but a collection of businesses, in aggregate, must and will make profits or progress stops.

And option 3 is the preferred route for many businesses in the growth stage of their lifecycle as they need continuous influx of capital to build and grow.

But as a business starts to mature with more profits coming in than it finding ways to profitably deploy, they start to return some of those profits back to the shareholders in the form of dividends and/or stock buybacks (indirect form of dividends).

So, of the total return you get investing in stocks over the long run, part of it comes from dividends and the remaining comes from appreciation through reinvestment of profits back into the business. But eventually, all the accumulated profits will be paid out as dividends.

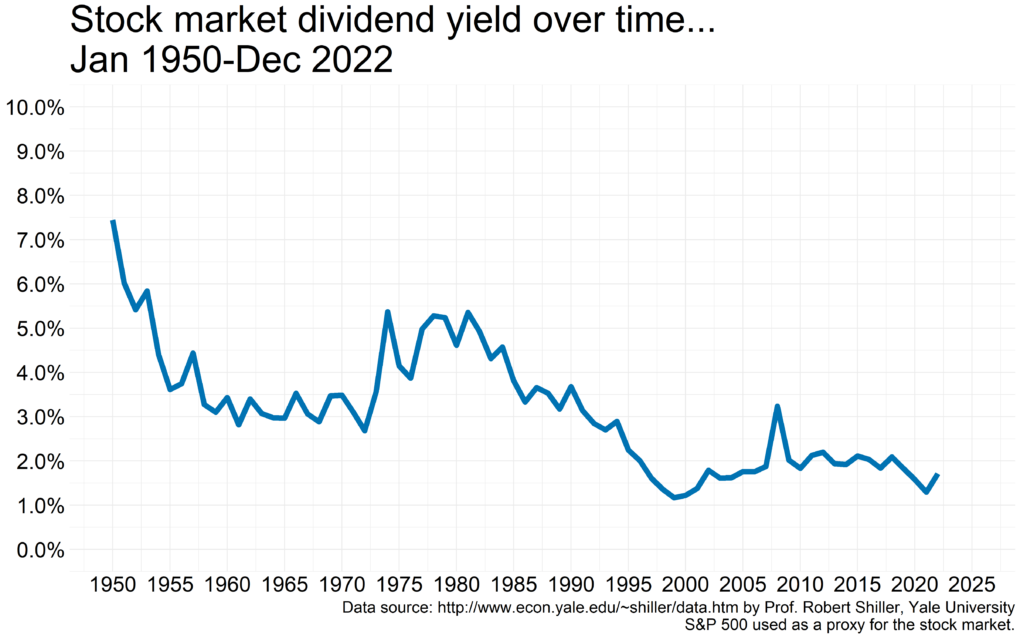

This below is the historical dividend yield for US large company stocks as represented by the S&P 500 index, a convenient proxy for stocks. Convenient because reliable historical data is available for S&P 500 but not so for the other corners of the market.

Dividend yields were higher during the 1950s because investors were still recovering from the trauma of the Great Depression followed by the Second World War. Nobody wanted to own stocks. To entice investors, businesses paid out almost all their profits as cash dividends. Stocks acted like bonds with profit growth muted due to limited reinvestment. That fortunately changed and here we are today.

But say you were transported back to 1950 (I love time travel) with the economy about to transform from catering to wartime industries into meeting domestic consumer demand of the post-war economy.

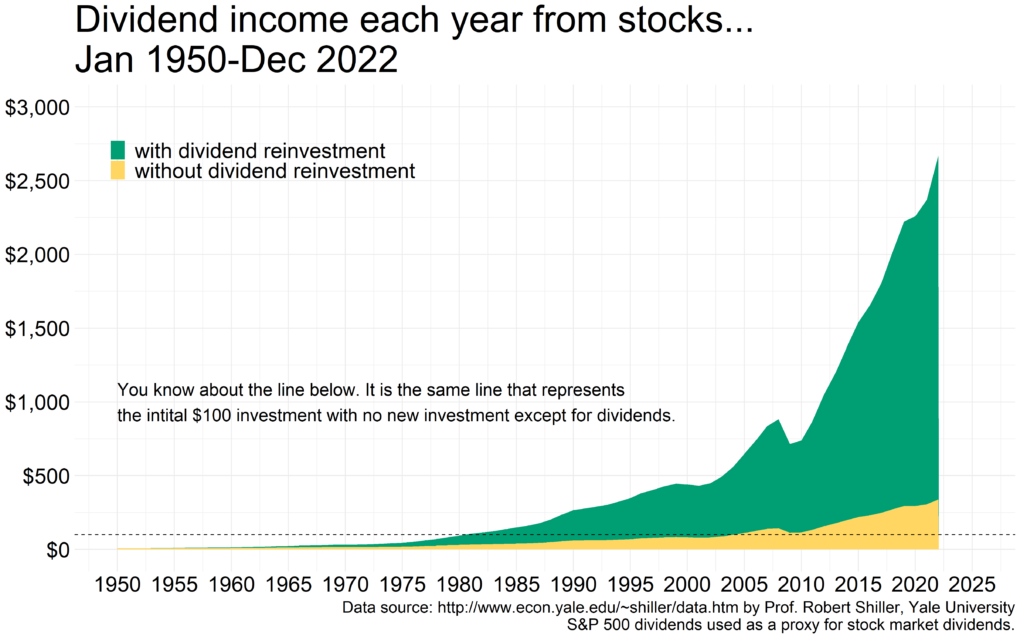

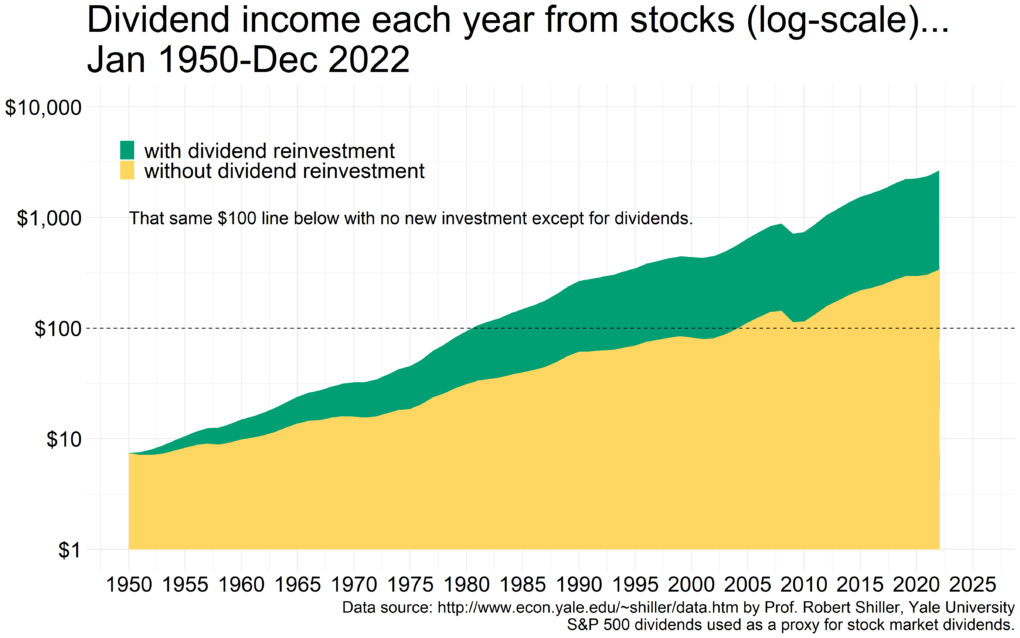

And say you as a baby happen to come into $100 through gifts that your mom then took and invested in the stock market. That money was then left to compound till today.

And say along the way, you had a choice to make; take the dividends out and spend them or reinvest them each year back into the same portfolio of businesses.

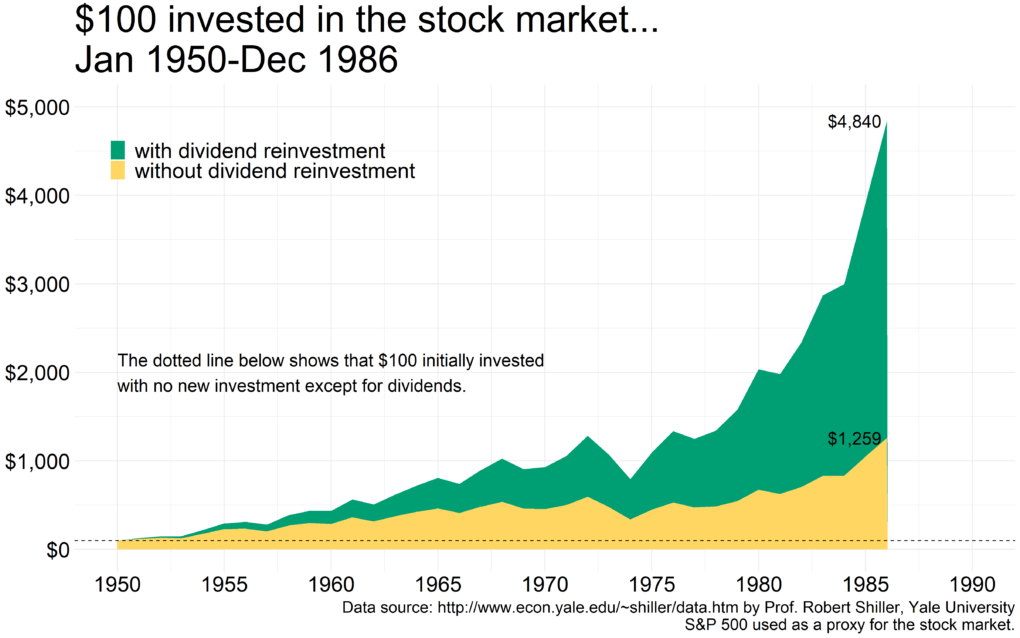

To highlight the compounding nature of this process, we will first look at the first half (1950 to 1986) of the 72-year timeframe.

The first half first…

The difference between dividends being reinvested vs. not reinvested is starting to diverge but does not look like it is as big a deal.

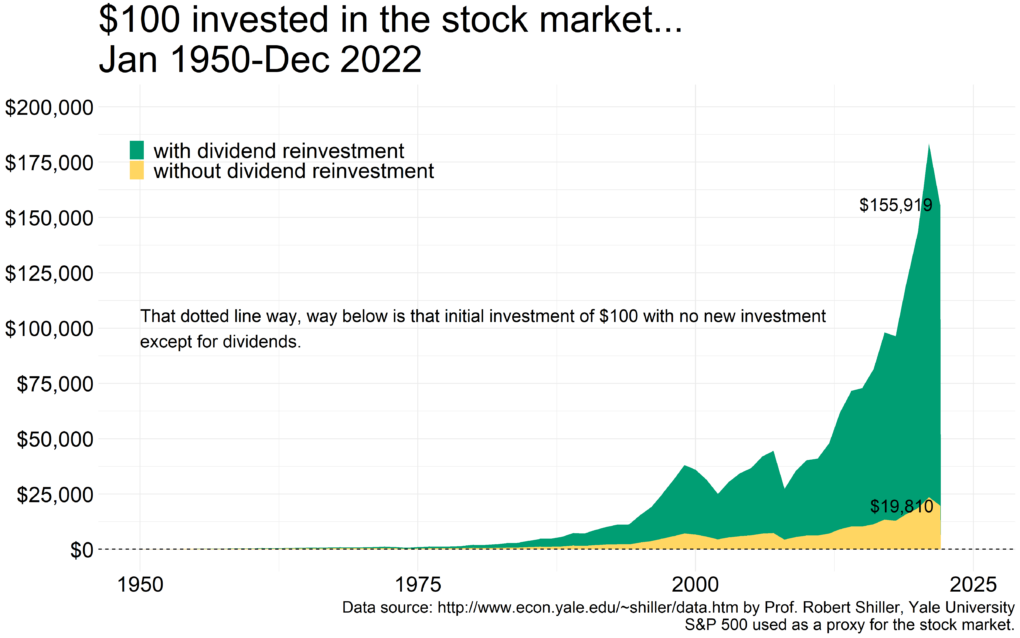

And then the law of compounding returns kicks in.

But you say $100 was big money back then for any family to save up. But then a pack of cigarettes cost 25c back in time. That is about 100 dollars’ worth of cigarettes each year if you smoked a pack a day. And many did. So, a manageable sum for any family.

And more importantly, how long did it take for that portfolio to throw off in dividends equivalent to the amount that was originally invested? Because that is what you are after. That is what will set you free.

Zooming into that $100 dotted line using log scale…

With dividend reinvestment, you got to the proverbial freedom in 30 years. Without that, you’d pretty much wait the entire timeframe.

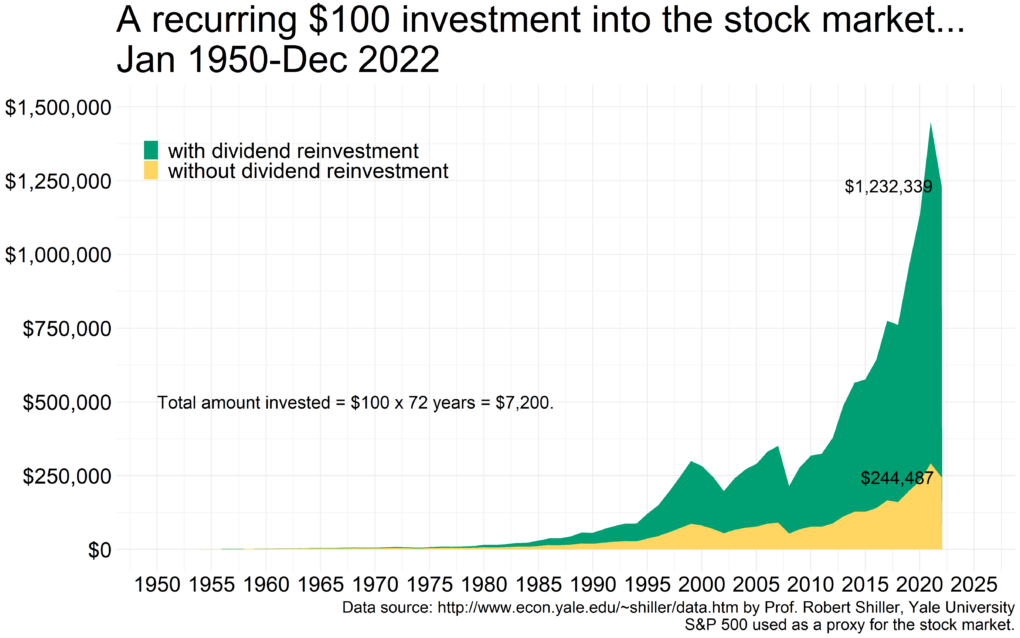

But why would anyone just invest once and call it a day? You’ll want to do it over and over again because that is what you are supposed to do.

So, take that same family and instead of investing just a single $100 at the start of the period, say they invest that sum every year through the entire timeframe.

And this is their final tally…

This is compounding returns at its best. The first half of the timeframe is hardly exciting, but the second half is equivalent to the DPU scale of progress of your savings.

A word of caution: now don’t go realigning your investments with dividends as the sole focus. Because you will likely end up with businesses that don’t have much juice left. You want natural dividends that are an outcome of the capital allocation decisions a diversified set of businesses make. You don’t want the businesses you own to go out of their way to make dividends available to you regardless of their ultimate cost. Because that will be like artificially curtailing progress and that will never be a good thing.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Julia Kuzenkov, Pexels