Albert Einstein is a universal symbol of genius. He discovered the theory of relativity, won a Nobel Prize in physics, and made scientific advances in gravity, cosmology, radiation, theoretical physics, statistical mechanics, and quantum theory. So wouldn’t an investor be blessed to have the smarts like his?

Einstein lost his savings – including his Nobel Prize money – on bonds that defaulted in the crash of 1929.

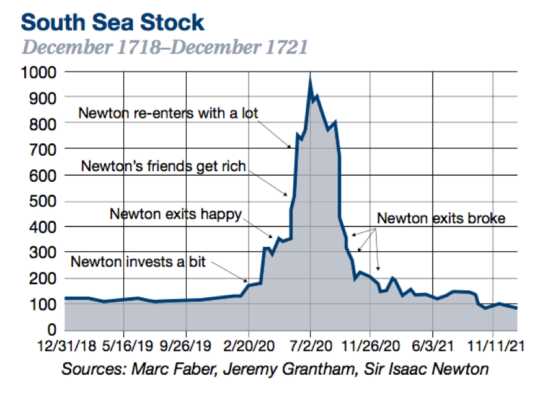

Sir Isaac Newton, one of the greatest mathematicians this world has ever known, was in fact a savvy investor. But even he couldn’t avoid falling victim to FOMO (fear of missing out). He lost the bulk of his wealth speculating in shares of the South Sea company.

But Einstein and Newton likely had better things to think about than money but not the folks running Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), a hedge fund built to manage other people’s money. LTCM was launched in 1994 by a team that included Nobel Prize winning economists and renowned Wall Steet traders. The fund was designed to profit from inefficiencies in global bond prices. The investment team behind the fund was supremely confident that they had eliminated all risks from their process.

And once you’ve eliminated all risks, why not lever up and bet big? So bet big they did, borrowing twenty-five times the equity base while accumulating positions to the tune of 1.25 trillion dollars.

But of course they hadn’t eliminated all the risks. So when Russia defaulted on its debt in the summer of 1998, it led to a series of cascading events that ended for the fund becoming insolvent. LTCM shareholders who made money hand over fist in the preceding years, lost it all in a matter of months. To contain the after-effects of that blow up, the then Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan had to orchestrate a bailout to unwind that setup. Investors in the fund lost everything.

Then we have Mensa and their investment club. Mensa is a society that welcomes people from all walks of life, provided their IQ is in the top 2% of the population. But these folks could stand to benefit by picking up a copy of Investing for Dummies. Eleanor Laise, a personal finance writer, analyzed the performance of the Mensa Investment Club between the years 1986 and 2001, a 15-year stretch when the stock market averaged 15.3% a year.

The Mensa Investment Club on the other hand eked out a measly 2.5% a year. That isn’t just lagging performance. It is more like getting left behind at the station.

Two things stand out from all this chronicling:

- Some of the smartest people in the world can make for being terrible at investing.

- Managing and holding on to wealth is hard.

Getting money and keeping money are two different skills. Getting money requires taking risks, being optimistic, and putting yourself out there.

But keeping money requires the opposite of taking risk. It requires humility, and fear that what you’ve made can be taken away from you just as fast. It requires frugality and an acceptance that at least some of what you’ve made is attributable to luck, so past success can’t be relied upon to repeat indefinitely.

Morgan Housel, Collab Fund

Because many think the investment process works something like this:

- You make an educated guess about the economy.

- You use that to build a hunch around what the stock and bond markets are going to do.

- You then pick investments based on that hunch.

- When things don’t pan out, you look for new theories and change your investments.

- Rinse and repeat.

On that note, the Wall Street Journal polls fifty-five of the nation’s top economists twice each year to gauge what lies ahead for the economy, interest rates and the dollar. Most get their forecasts wrong. Their consensus don’t look that hot either.

Pity the poor Wall Street economist. Big staffs, sophisticated models, reams of historical data, degrees from Ivy League schools and still they forecast about as well as groundhogs.

Jesse Eisinger, Wall Street columnist

And it is not their fault. Forecasting anything to do with a complex, adaptive system that is the global economy is hard. And here we are, investing our life savings based upon literal hunches.

I am not a fan of watching mainstream financial media. In fact, I seldom do. But we have all seen these experts come on these shows and recommend investments as if that is all it takes.

Because they don’t know you. They don’t know about you. It is a great deal for them when you watch these shows but a very, very bad deal for you if you act upon the mostly non-contextual advice being dispensed.

The solution then is to come up with a good process, a process built with you and your lifecycle in mind, a process that is going to reliably take you to your goals and beyond.

And a process built around contextual nudges along the way just like how a captain steers his ship towards its destination.

Getting the process right is critical. A bad process with a temporarily great outcome is when you get LTCM-type situations. Never invest in anything when you know deep down that there is something off with the process.

And never stop investing when you know that the process is right, but the outcome is temporarily dull. In fact, it is a great deal for you if you are an aggressive saver.

But once the process is figured out, letting the investment returns fall where they may within a rough probabilistic band while applying tax-optimized tweaks along the way is how you get to your goals.

Behavioral finance says that emotions play a big role when holding on to investments, especially investments of the paper kind that we own in our many accounts. Because it’s easy to hold on to houses. They are illiquid. We don’t see their price volatility. We can touch and feel them.

But holding on to financial assets requires conviction. And conviction does not come easy. It takes a concerted effort for years.

Yet you are never done. It is a forever endeavor.

But building conviction in the process that feeds a good-enough plan while affording a great life is how we win.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Yaroslav Shuraev, Pexels