Fresh out of school and ready to take on the mean, bad world, you go find yourself your dream job. And with that comes access to a workplace retirement plan like a 401(k). Not all employers offer one but then you deem yourself lucky.

So, an enlightened 25-year-old that you are who knows what time does to a little bit of savings, you jump all in and contribute to the maximum dollar amount allowed. You do that for a few years and now you are sitting pretty with an investment balance of $50,000 in your plan.

And then the market takes off by another 20% so now you have $60,000.

You are happy.

But here is the problem. You just started with this whole retirement thingy with a lion share of your contributions still to occur into the far future. That 20% bump in market price of your investments means any new contributions you make in your plan will cost 20% more…for the same investments.

That same bump though during the later stages of your work life is a completely different ballgame. We are talking real money here assuming you did all you needed to do savings-wise, while you were working.

You want the big gains to come later in your life with itty-bitty gains during the early and middle phases. I mean you want the markets to go nowhere while you are working and feeding your plan with fresh savings.

And then right when you are about to retire, you want the biggest, baddest bull market in history to allow for all that dry powder in the form of accumulated savings to explode. That’s the ideal and only a lucky few get to live it. Lucky not just from the perspective of timing but lucky from the perspective of persevering through it. Let me explain why.

Say you happen to start work in January of 1966 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average stood at a mere 1,000 points. It would continue trading below that mark for the ensuing seventeen years.

Imagine watching the market go nowhere for seventeen long years?

The Dow once again breached 1,000 points in December of 1982 before finally breaking out, never to look back. That by the way happened to be the setting stage for one of the greatest bull markets in stock market history.

So, if you entered the workforce in 1966 and started to stuff your investment accounts with fresh savings, you bought more and more of business profits at constant to down prices at every chance you got.

And by the time the market turned, you were technically done. I mean your savings did all the work while you chilled.

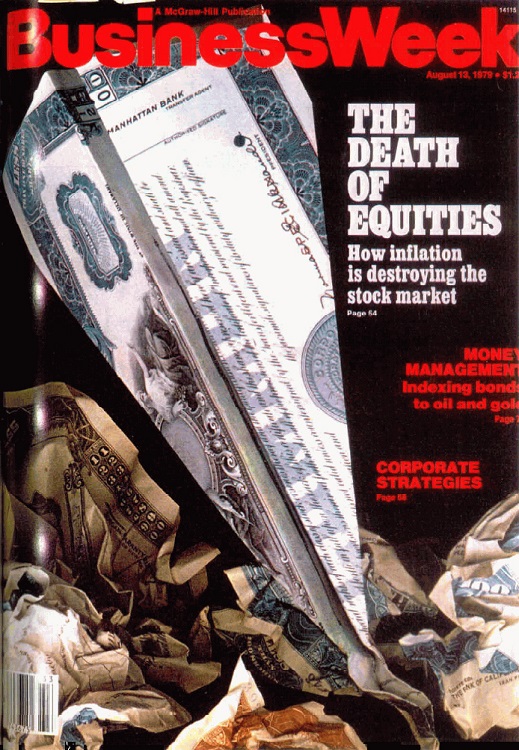

But with headlines like below towards the later stages of that extended bear market, how many folks do you think remained invested? And how many at that kept feeding their plans for the entirety of that period? Bet not many.

Because to stick with your investments for that long of a “flattish-performance” requires conviction. And conviction comes with knowing what you are investing in and why. This all gets into the murky world of business valuation and market history and portfolio theory and the rest of the stuff that I usually bore you with but let me put it this way, conviction takes time.

But without conviction, you won’t have a plan. Because you’ll bail at the worst of possible times and then it’s mostly over.

But guess what people were “investing” in back then? In gold.

And in other precious metals. Yuck.

You did 20 times your money in gold during the decade of the seventies when stocks treaded water.

Source: Macrotrends

But we know gold is not an investment. It can never be an investment. No commodities are investments.

And you think people got into gold before that big run-up? Not a chance. They got in right when that cycle was about to end. And that cycle likely ended forever.

Why do I say that when we clearly see the price of gold quite a bit higher today than that during the seventies? Because we haven’t factored in inflation yet.

Source: Macrotrends

So, if you bought into “gold as an investment” and an “inflation-hedge” theories back then, you’ll be sad today.

But back to the main discourse, what appeared to be the worst of times to invest back in the day when the stock market treaded water was in fact the best of times.

And had you stayed invested and continued to plow new money into the markets, you made out like a bandit.

How do I know? Because the next ‘no growth’ phase in the domestic stock markets came about during the decade of 2000s, right after the Dot-com bubble burst. The “market” as quoted by the S&P 500 was down for the entirety of that decade.

But had you stayed invested and continued to plow new money, well, you know the story.

Also, that ‘no growth’ phase in the U.S. stock markets applied mostly to the growth stocks of the era that stayed flat during that decade. Value stocks did just fine. Small caps did okay but international stocks is where all the action was.

That story flipped again in the decade of 2010s. Growth stocks did great but value and international underperformed.

Could the cycle turn again? We don’t know. We’ll only know that in hindsight.

But our investment plan must account for that. In fact, it must account for all possible scenarios. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. Outcomes are not in our control, but the process is. Investing and planning for decades requires getting that process right. Outcomes then fall in place on their own.

But getting the process right also means that we’ll always end up owning something that temporarily sucks. Markets move in cycles. We just have to wait for those cycles to work their course.

And sometimes, working through those cycles can stretch into years but whatever the case, don’t fear market declines. Embrace them, especially when you are a literal baby in the grand scheme of things.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – David Bartus, Pexels