Say someone you know is running short on funds and comes to you for a loan that he promises he will pay back in a month. Will you lend him the money? And if so, would you do it for free?

You think why not. You have loaned him the money before and without fail, pays you back on time.

But say that same someone comes to you for a loan that he promises to pay back in a year? Would you loan him that money for free?

It is different this time, right? Money devalues over time so waiting a year means you are losing purchasing power.

Or say a loan that he will pay back in a decade? Now that is a risk.

The longer the duration, the greater the chance you will not see your money back in some form or the other and hence, the greater the risk.

And the greater the risk, the higher the interest you will demand on your loan.

That same thing plays out in the bond market. When you lend money, you are in fact buying a bond regardless of whether you are lending it to a friend, to a government or to a business. They do have different risk profiles as they should but inherently, it is the same.

United States Treasury bonds are some of the safest bonds you can buy. They range in maturities from 30 days to 30 years. A bond matures when the loan term ends.

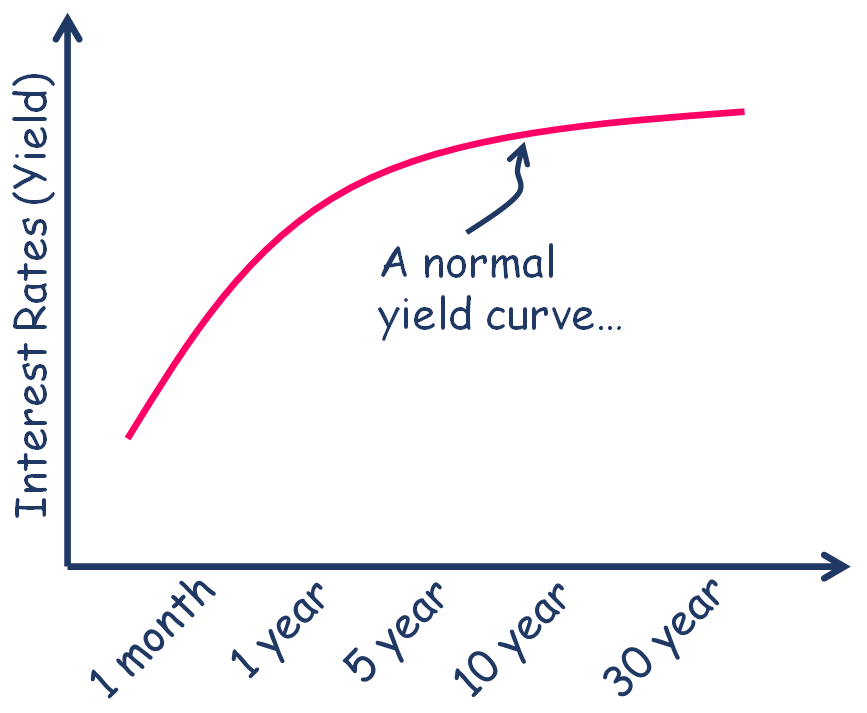

So between say a 30-day bond versus a 30-year bond, which one do you think should pay a higher interest rate?

The 30-year bond, of course.

A lot can happen in 30 years whereas not much usually happens in 30 days. By investing in a 30-year bond, you are giving up access to your savings for a much longer duration, hence a greater risk.

And in return, you’d demand a higher interest rate.

So interest rates gradually slope up as bond durations rise. That is the yield curve and it makes intuitive sense.

Now if yields on short duration bonds start to rise while yields on long duration bonds remain unchanged and they rise to a point where now both the short and the long duration yields are the same, that’s a flat yield curve. It does not make logical sense that that should ever happen but it does every once in a long while. The yield curve starts to flatten when the yield on a 10-year Treasury bond approaches that of a 2-year bond.

But when the short duration bond yields rise to a point when now they are higher than the long duration ones, that is an inverted yield curve.

But why would a yield curve flatten? Or invert?

We hear about the Federal Reserve raising or lowering rates and we think they control all interest rates.

But they only control the overnight rates that they charge banks for the use of the money. That duration is only a day so that is the shortest of the short end of the yield curve.

Longer term rates like what we pay for mortgages and car loans are at the mercy of the markets, their expectations of growth rates and inflation.

And the Federal Reserve does not care much about the shape of the yield curve. All its charter is to make sure that the economy has full employment and stable prices.

That is, the Fed wants anyone looking for a job to be able to find one while ensuring that inflation remains tame and deflation never takes hold. Ever.

And they engineer that by manipulating the overnight rates they charge banks.

When unemployment is low but inflation is raging, the Federal Reserve will act to slow things down by raising the cost of borrowing.

Raise the short-term rates with no impact on the longer-term rates and the yield curve flattens.

And that can result into a recession so investors naturally get concerned.

But recessions are part and parcel of a healthy economic cycle. No one can predict their timing though but nothing about your long-range financial planning should change with whatever is happening with the yield curve.

Because yield curve changes are temporary while your investment timeframe is rather permanent.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – DreamLens Production, Pexels