Say you decide to play blackjack with a friend, and you play to a point where one of you wins everything from the other.

And say the game starts with $100 from you and another $100 from your friend and ends when either of you goes home with $200. The net wealth in the system (the game) started at $200 and ended at $200. The only thing that changed is how that money got divvied up.

A concept from game theory, this is an example of a zero-sum game. For you to win, your friend must lose. For you to lose, your friend must win. The net wealth in the game though, remains unchanged.

Each game of blackjack you play with your friend is a zero-sum game and say you play that game every day for five years. And assume each of you are equally skilled at that game. Some days you win, other days your friend wins but in the end, each of you will end up with the same amount of money you started with.

And just like before, the net wealth in the system remains unchanged. This is a longer-term view of a zero-sum game.

Playing blackjack at a casino is worse than a zero-sum game because now the casino wants its cut, and that cut is coming from you. So, what started as a zero-sum game is now a negative-sum game for you and a positive-sum game for the casino. It must be that way, or the casino won’t stay in business.

So, if you win playing the casino, consider yourself lucky. But never mistake luck for skill because play there long enough and you’ll lose. That is by design.

Playing the lotto is a big negative-sum game for you and a hugely positive-sum game for the state sponsoring that lotto.

Trading in commodity futures, if you have no business trading in them, is another example of a zero-sum game. For someone to gain on a contract, another someone at the other end must lose. Take taxes and transaction costs into account and that seemingly zero-sum game quickly turns into a bigly negative-sum game.

And if you don’t know what commodity futures are, you don’t ever need to know unless you are in the business of dealing with stuff that you’ll use in your business, and you need some certainty around that stuff’s future prices.

For example, if you are running an airline, you might want to lock the price of oil say six months out by buying an oil futures contract. If you are not running an airline and you are trading in oil futures, don’t.

What other negative-sum games do we play knowing full well that we are going to lose but this time around, we don’t mind? Life insurance.

You buy a policy and pay premiums all along, but the worst-case scenario never happens. And you are glad it never happened. The insurance company facilitating this whole thing will take its cut but that is a good thing because when you buy life insurance, you are buying peace of mind. You are insuring your income for your family against you prematurely dying.

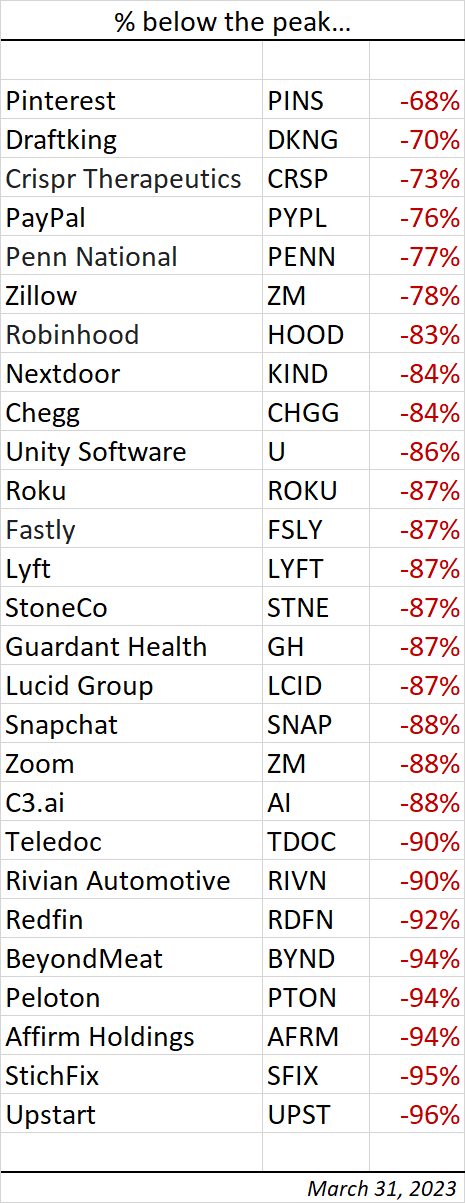

Day trading stocks is another example of a zero-sum game before taxes and transaction costs and a big negative sum game after accounting for those costs.

Then there is options trading on stocks and there are reasons for it to exist, but retail investors should never be allowed near that. It is a hugely negative-sum game after taxes and transaction costs with oftentimes tragic life changing consequences…

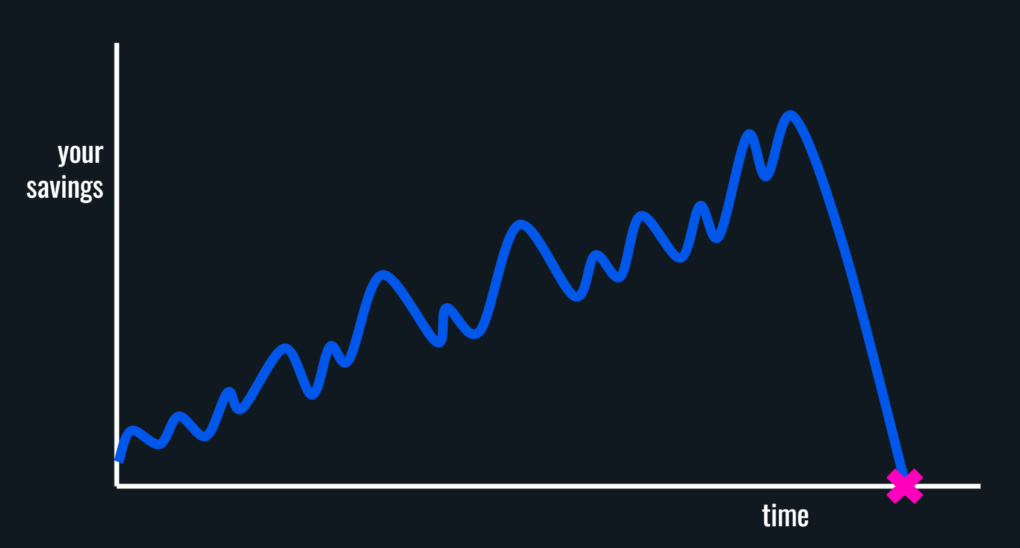

Krurd, as it turns out, is a 35-year-old unmarried Chicago psychiatrist who had invested, and subsequently lost, nearly $1 million — all of his savings — in call options on Bill Ackman’s special-purpose acquisition company, Pershing Square Tontine Holdings, before it found a merger partner and inked a definitive agreement, or DA.

How Millennial Investors Lost Millions on Bill Ackman’s SPAC

Michelle Celarier, Institutional Investor, August 11, 2021

$1 million at age 35 is all you need to be set for a fantastic retirement life. But now all gone in the blink of an eye.

These men — and they all happen to be men — are immigrants, first-generation Americans, and children of the blue-collar working class who have excelled in their professions. They are now engineers, small-business owners, doctors, consultants. Some went to Harvard, Princeton, UCLA. Many were the first in their families to attend college; a few are still students.

They are millennials — ranging in age from 24 to 39 — who live in New York, California, Illinois, Maine, Utah, and Texas, as well as Germany and Canada. They all lost money in Tontine — in at least one case more than $2 million — as SPAC mania swept through the stock market like wildfire over the past year.

How Millennial Investors Lost Millions on Bill Ackman’s SPAC

Michelle Celarier, Institutional Investor, August 11, 2021

The write-up also talks about a 39-year-old software engineer who scrimped and saved $1.6 million over twenty long years and rightly afraid of losing any of it, kept it all in a bank account. Not the best of deals but worked for him because he did not know any better.

And then lost it all on call options that expired worthless in a matter of days.

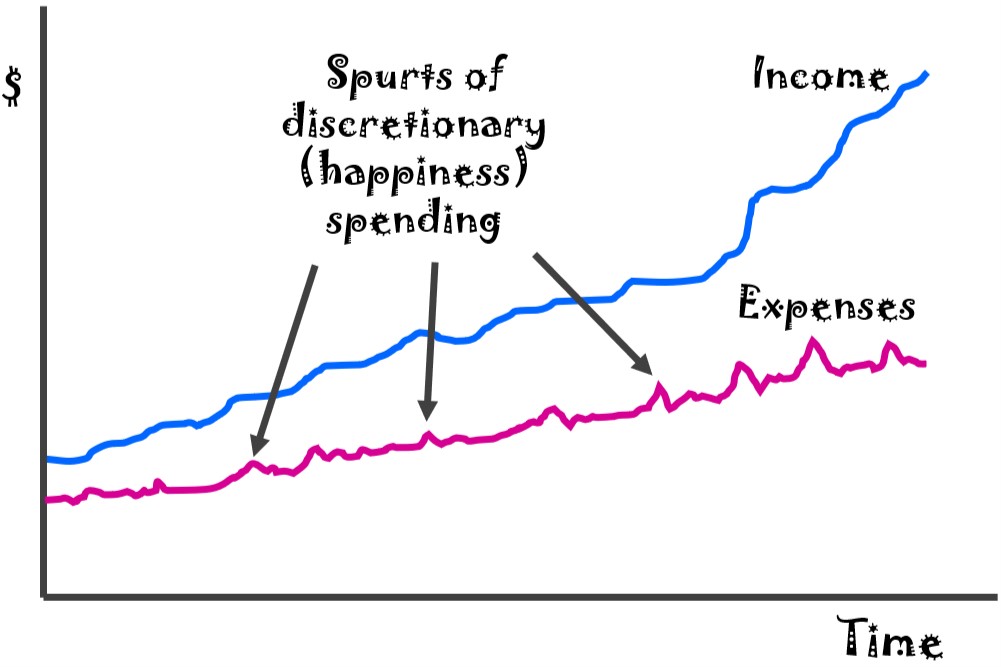

But back to stocks, day trading them is the dumbest thing you could do with your money. Because stocks are not just little digits on your screen. They represent partial ownership in real businesses that make real products.

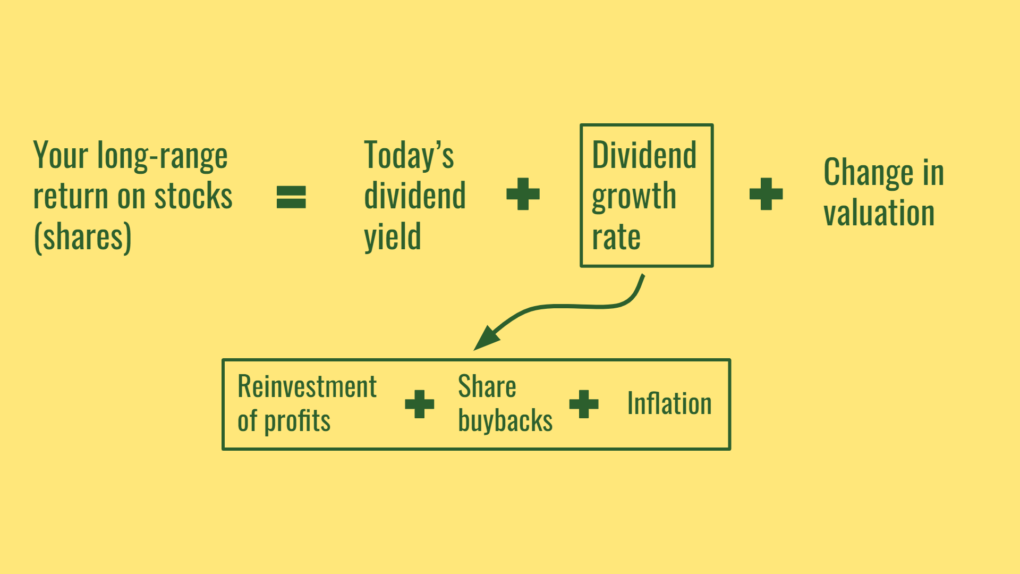

I consider day trading as any activity that is short of perpetual ownership of businesses while you wait for the cash flows in the form of dividends to flow to you until that business has run its course.

But owning one or two businesses entails the risk of those cash flows from ever materializing so you own a bunch of them. And then you sit tight and wait.

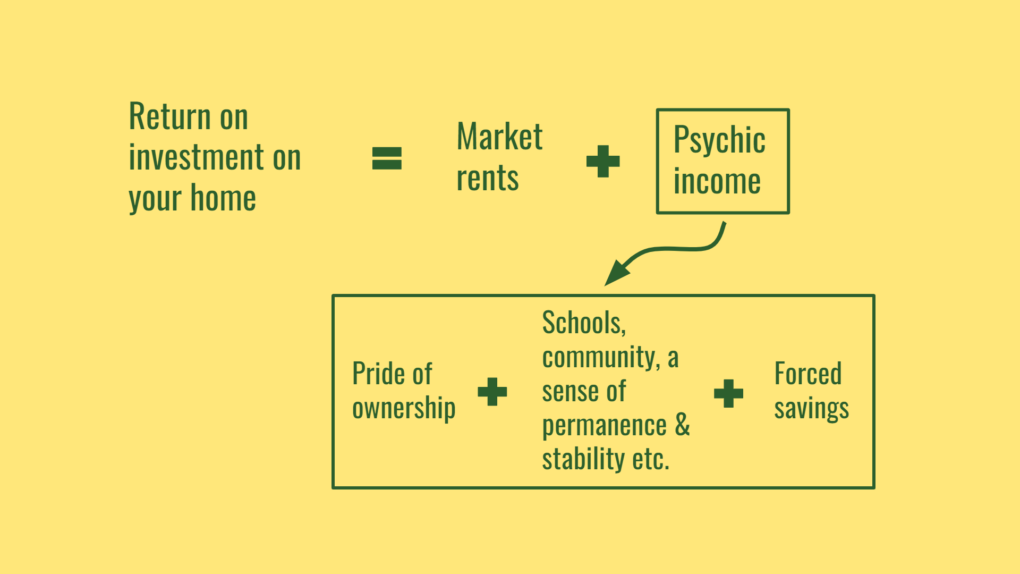

The only positive-sum game hence, in the world of investing is long-term, perpetual ownership of businesses; businesses that power and feed our ever-growing economic pie; businesses that are run by some of the brightest of folks around; businesses with all their buildings and machines and processes working in unison to create the magic we see all around us. You’d want to forever own a piece of that magic.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Gladson Xavier, Pexels