Cornelius ‘Commodore’ Vanderbilt, the American railroad and shipping tycoon, died in 1877 and left behind a $95 million fortune to his eldest son, William H. Vanderbilt.

$95 million might not put you anywhere in the Forbes 400 list today but that was more money at the time than was held in the United States treasury. What happened to that great fortune is chronicled in a fascinating tale by Arthur T. Vanderbilt in Fortune’s Children, The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt.

William, having watched his father handle money, learned a thing or two about wealth management. He took the $95 million that he inherited and turned it into $194 million by 1883. That made him the richest man alive at the time. That’s like 500 billion dollars today if invested at a conservative 6 percent rate of return each year.

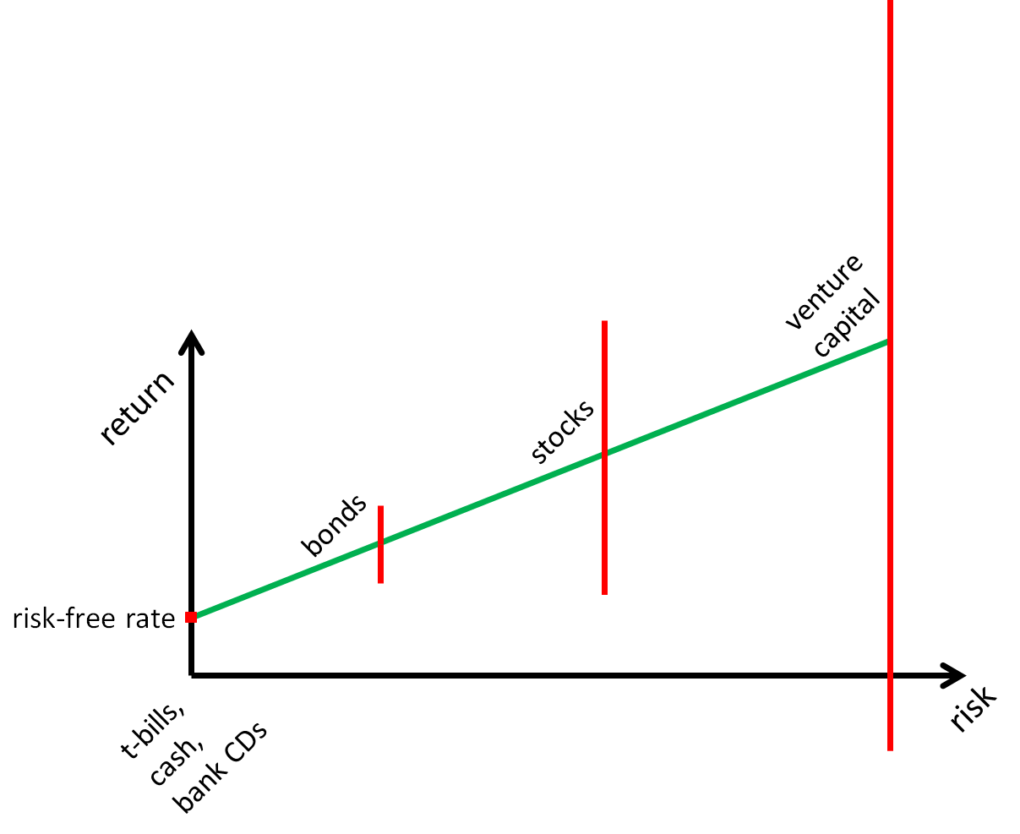

And 6 percent is conservative because the money, if invested, had the tailwind of the United States growing from an emerging economy back then to the powerhouse it is today.

What is the current state of the Vanderbilts and how come we don’t hear much about them?

This fabled golden era, this special world of luxury and privilege that the Vanderbilts created, lasted but a brief moment. Within thirty years after the death of Commodore Vanderbilt in 1877, no member of his family was among the richest people in the United States, having been supplanted by such new titans as Rockefeller, Carnegie, Frick, and Ford. Forty-eight years after his death, one of his direct descendants died penniless. Within seventy years of his death, the last of the great Vanderbilt mansions on Fifth Avenue had made way for modern office buildings. When 120 of the Commodore’s descendants gathered at Vanderbilt University in 1973 for the first family reunion, there was not a millionaire amongst them.

That colossal wealth was squandered on colossal homes…

Her second demand was that it be bigger than Marble House. And it was, with its four stories, seventy rooms, thirty baths with hot and cold fresh water and salt water piped in from the sea, and thirty-three rooms for the servants. The eleven acres surrounding the mansion were covered with sod imported from England, and numerous thirty-ton trees planted around gave the place an appropriately venerable look.

Construction began in the spring of 1893. With the work of two thousand laborers and artisans and artists, some working during the day, others at night with the aid of electric lights, The Breakers was ready for occupancy in the summer of 1895, an amazing accomplishment in a day when all work was done by hand, by pick and shovel, and with horse-drawn carts. Limitless wealth could indeed accomplish anything.

It had been worth the $7 million it cost (plus the millions more to furnish it).

That is an easy all in $10 million at the time. The present value of $10 million at 6 percent a year is about 15 billion dollars, making it one of the priciest homes ever. And her in the excerpt above refers to Alice, the grand-daughter-in-law of the Commodore who wanted to build a bigger, better house than her sister-in-law Alva’s Marble House.

That was just one home amongst several others.

And when you have that kind of money, you host the best of parties. For instance, Alva spent $250,000 in 1883 dollars on a single night hosting the who’s who of society at the time to proclaim the arrival of the Vanderbilts. Present value of $250,000 compounding at 6% for all those years ~ $800 million.

A substantial chunk of the wealth was also literally gambled away.

On December 19, 1901, his twenty-first birthday, Reggie inherited $7.5 million outright under his father’s will, plus $5 million from another trust fund.

Reggie, the great-grandson of the Commodore

The present value of the money Reggie inherited ~ 15 billion dollars.

And of course, when there is inherited money, family feuds and rivalries follow which make each outspend the other to a point that leads to this…

The sale of Idlehour…

For $460,521, Harold sold Idlehour, the eight-hundred-acre estate on Oakdale, Long Island, with its three-story marble and brick manor house containing thirty master bedrooms, its large conservatory, and its tennis court under glass, all of which had cost Willie over $10 million.

The sale of Marble House…

But finally she relented, and in 1932 sold it to Fredrick H. Prince, the head of Armour Company, for the Depression price of $100,000 – less than one hundredth of what Willie had paid for Alva’s thirty-fifth birthday present.

The eventual financial state of Alva, the grand-daughter-in-law of the Commodore, in 1933…

At the time of her death, after a lifetime of buying and building, she was down to her last million. Her estate was valued at $1,326,765.

When all was said and done…

The Fifth Avenue mansions, gone. The New York Central, gone. And the country homes, how did they fare? Idlehour. Marble House. The Breakers. Belcourt Castle. Biltmore. Beaulieu. Wheatley Hills. Vinland. Florham. Not one was used by the next generation.

The fact that it took precisely three generations to complete the rags to riches to rags cycle makes a lot of sense. The first generation starts somewhere at the bottom, works hard, saves, and invests diligently to a point where worldly comforts become the norm.

The second generation, watching their parents’ metamorphosis from struggling upstarts to affluence, start to incorporate some of what they saw and learnt growing up into their own lives. But the fact that the first generation did everything right meant that quite a bit of that behavior trickled down to the generation next.

But the second generation does not need to try as hard, and abundance is all they experience. But because there is no struggle there, by the time the third generation rolls around, it is all The Rich Kids of Instagram. No hard choices to make, no corners to cut, life is easy.

And regardless of the size of the inheritance, it does not take much to spend through all of it and more and hence by the time the fourth generation rolls around, all is gone, and the cycle starts over again.

This is not just anecdotal evidence based solely on the story of the Vanderbilts or how I perceive this bust-boom-bust cycle transpires. Data compiled by The Williams Group in a study of more than 3,200 families found that 70% of the wealth dissipates by the end of the second generation and almost 90% by the third. Hence the old saw, “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.”

But along the way, the book dispenses some important life takeaways. First, wealth management is hard.

By his early sixties, he was tired and worn out. “The care of $200,000,000 is too great of a load for my brain or back to bear,” he confessed to his family. “It is enough to kill a man. I have no son that whom I am willing to afflict with the terrible burden. There is no pleasure to be got out of it as an offset – no good of any kind. I have no real gratification or enjoyments of any sort more than my neighbor on the next block who is worth only half a million. So when I lay down this heavy responsibility, I want my sons to divide it, and share the worry which it will cost to keep it.”

This is William H. Vanderbilt, the successor to the Commodore’s fortune, lamenting his state to someone close.

And realizing how difficult it is to hold on to wealth, the Commodore himself at one point confides to a friend of his with this quote from the book…

Any fool can make a fortune. It takes a man of brains to hold on to it after it is made.

Second, inherited wealth seldom leads to happiness and life satisfaction.

Willie indeed had it all: good health, good looks, good friends, and good fun, and an ever-growing fortune that enabled him to do anything anyone could do. He also had the intelligence to perceive that perhaps having everything left a lot to be desired. On one of his trips back to the United States from his French stables, he talked with reporters in extraordinarily candid terms about what it meant to be rich. “My life was never destined to be quite happy,” he told them. “It was laid out along lines which I could not foresee, almost from earliest childhood. It has left me with nothing to hope for, with nothing definite to seek or strive for. Inherited wealth is a real handicap to happiness. It is as certain death to ambition as cocaine is to morality.”

He continued lecturing the astonished reporters: “If a man makes money, no matter how much, he finds a certain happiness in its possession, for in the desire to increase his business, he has a constant use for it. But the man who inherits it has none of this. The first satisfaction and the greatest, that of building the foundation of a fortune, is denied him. He must labor, if he does labor, simply to add to an oversufficiency.”

That is Willie, the grandson of the Commodore describing the perils of inherited wealth.

Morgan Housel, one of my favorite personal finance writers, says that he wishes his son experiences poverty at least once in his life.

Jonathan Clements, in one of his many books, lamented the fact that he feels providing a life of relative comfort to his kids has somehow deprived them of their ability to hustle and make things happen. That lack of ambition is a real handicap to achieving lasting happiness, the happiness one derives through hard work and relishing the fruits of one’s labor.

Celebrity chef Nigella Lawson has no intent of leaving a substantial inheritance to her children because she knows that not having to earn money ruins lives.

And then we have the Buffetts of the world who have pledged to donate all their wealth rather than leave large inheritances. As Warren Buffett famously said, he wants to give his kids enough money so that they have the freedom to do anything they want, whatever it pays but not so much that they do absolutely nothing.

And if you want to see what life was like growing up in the Buffett household, I highly recommend a book by his son Peter Buffett, Life Is What You Make It: Find Your Own Path to Fulfillment.

Working hard and overcoming some of life’s struggles provides satisfaction that inherited wealth cannot. We should want our kids to experience some of those struggles to help provide meaning and purpose to their lives.

I grew up in India and life is an unimaginable hardship being poor in a country like that and I think there is a distinction between being poor in India versus say, being poor in any of the Western countries. It is a monumental task for a kid born to a family living on the streets in a country like India to break out of that cycle as opportunities for upward mobility are limited.

But then affluence and a path towards upward mobility was not always a given in these United States either…

Before the Civil War, there were fewer than a dozen millionaires in the United States. In 1892, the New York Tribune published a list of 4,047 millionaires, over 100 of them having fortunes that exceeded $10 million. It was estimated that 9 percent of the nation’s families controlled 71 percent of the national wealth. As the self-indulgent old rich and the new rich flaunted their wealth, paying on average $300,000 a year to maintain their city mansions and Newport cottages, $50,000 to keep their yachts afloat, and $12,000 each time they wanted to give a little party, hundreds of thousands of immigrants were jammed into tenements not far from the fabulous Millionaires’ Row. Thousands of child laborers worked in sweatshops for $161 a year. Common laborers made $2 to $3 a day, with the average worker earning $495 a year. Two thirds of the nation’s families had incomes of less than $900; only one family in twenty had an income of more than $3,000.

But even in a country like India, that cycle of rags to riches to rags persists because all it takes is one generation to come along that has no clue how it is done and then it is back to square one.

So, some more takeaways…

First, my perspective on leaving a legacy behind has evolved greatly. That would be an understatement. I would say the more I have read on this, the more convinced I am that there is no point killing ourselves in our day-to-day life if in the end we leave a pile of cash behind so that our next of kin gets to ride easy. There’s this very famous father-son interaction in a hit Bollywood movie where the father wants his son to live his part of the good life as he, the father could not because he was too busy making money. Fine because there is a certain amount of pleasure we derive seeing our kids enjoy the wealth we were fortunate enough to create.

But that does them more harm than good in the long run in light of all the evidence that is out there, and the way human nature works. So, the best use of our money is to plan it in such a way that we get to spend it all. And bequeaths to our favorite charities are included in that spending bucket.

That is not to say that we don’t do nothing for our kids. Paying for their education, providing them with options to pursue their passions etc. are all things we can buy for our kids. But outright raising trust-fund babies is not going to turn out good.

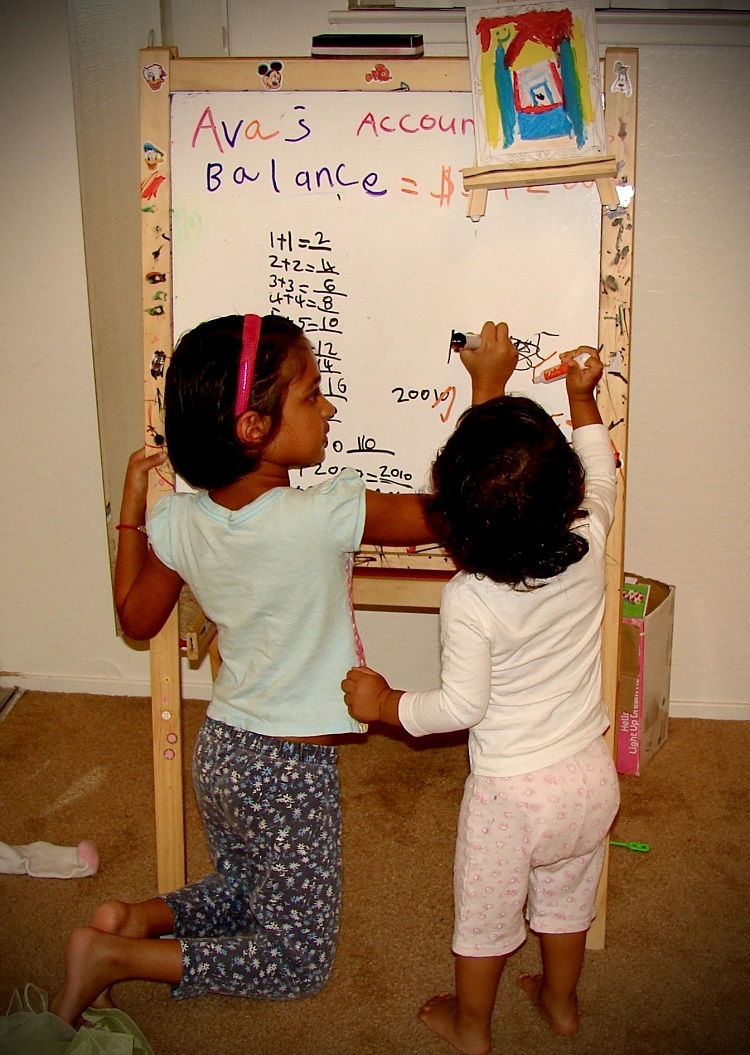

Second, getting our kids involved in the little and big decisions we make with our money is a great way to impart some of what we have learnt onto them, age no bar. The more action they see, the better off they’ll be. And we hope they do the same with their kids.

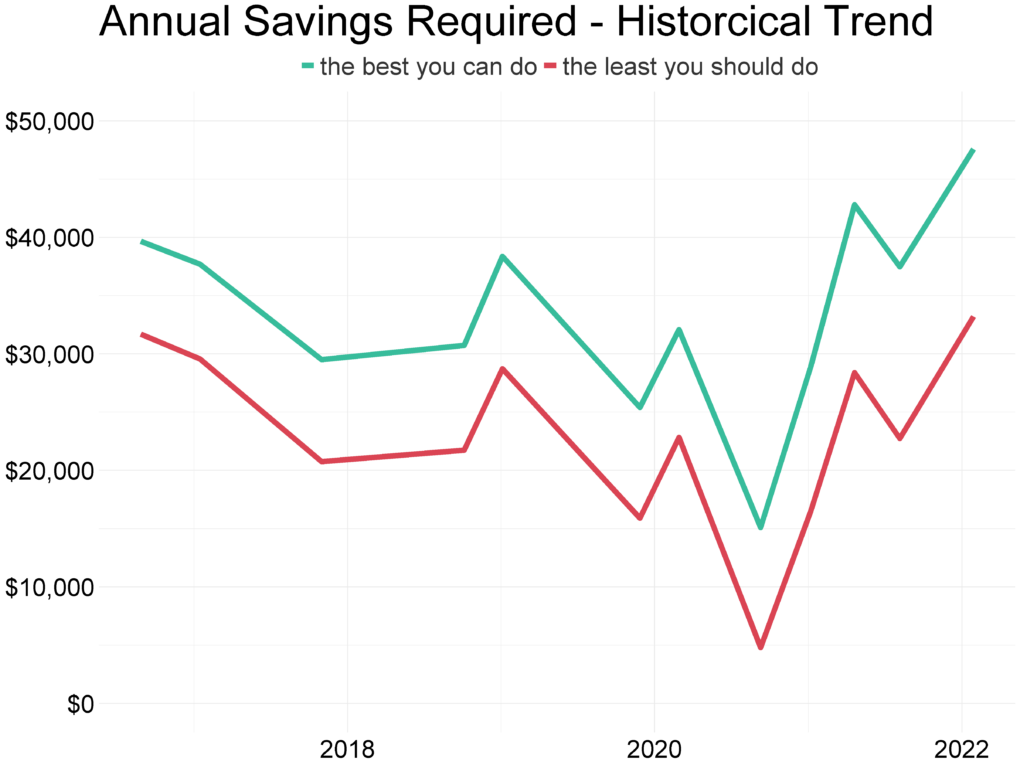

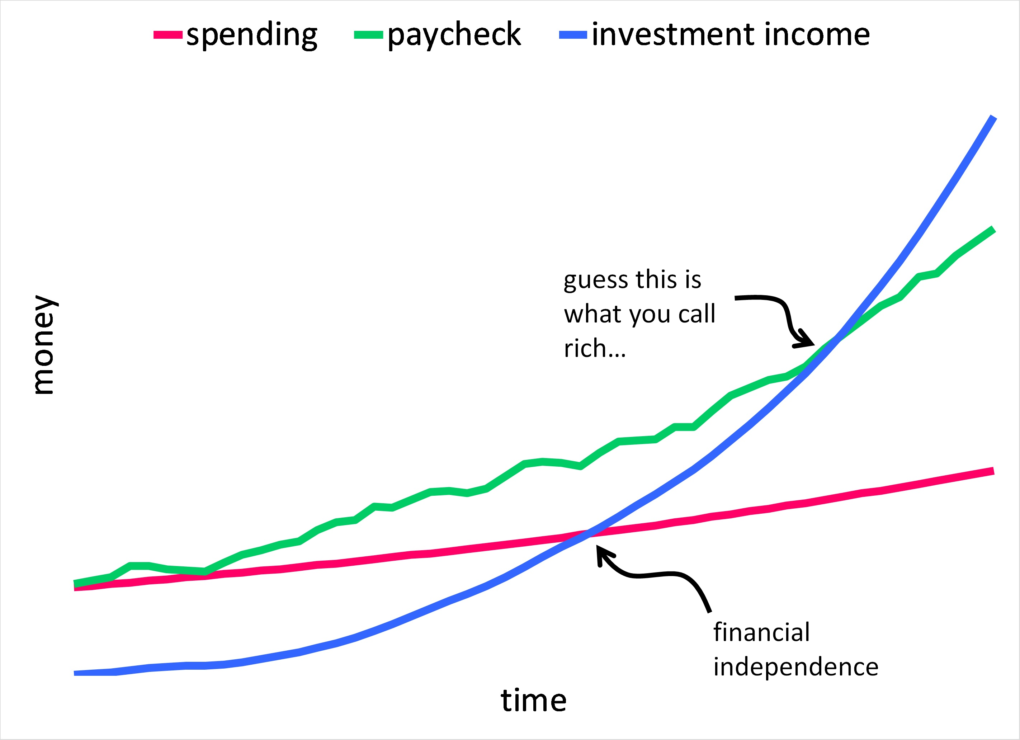

Third, financial literacy is a skill our kids must learn to thrive in the current state of our economy. We see everyday implications of not knowing this stuff with the level of student loan, credit card and mortgage debt out there. Plus, no more pension plans coupled with longer lifespans mean that the retirement thingy is not looking that hot either for a vast majority of people.

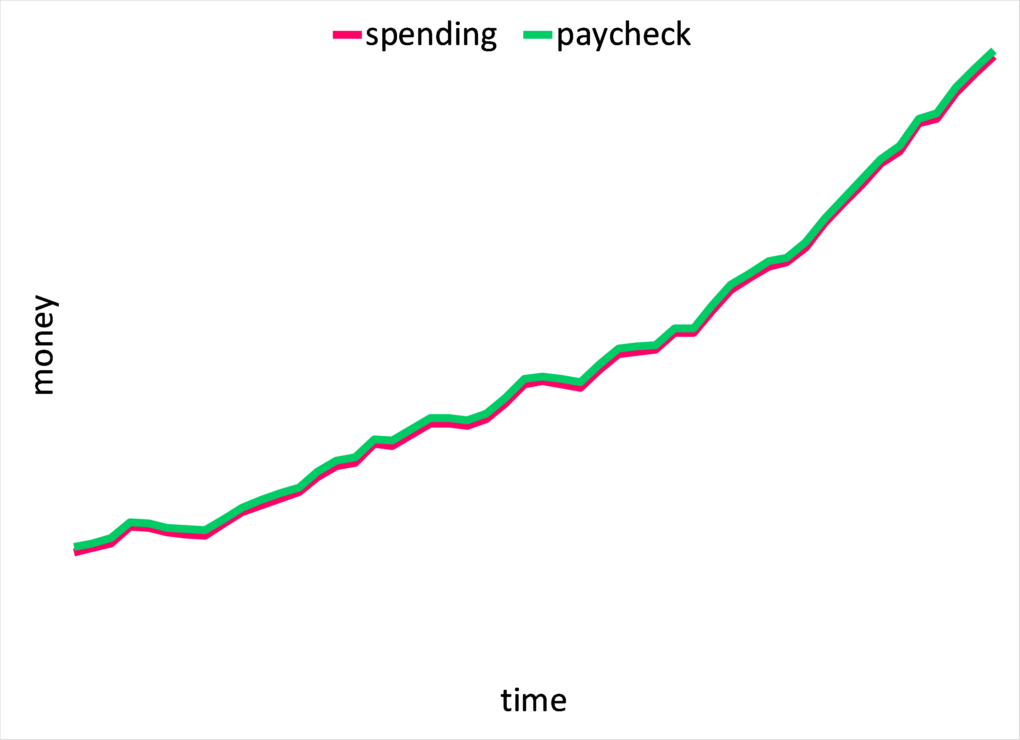

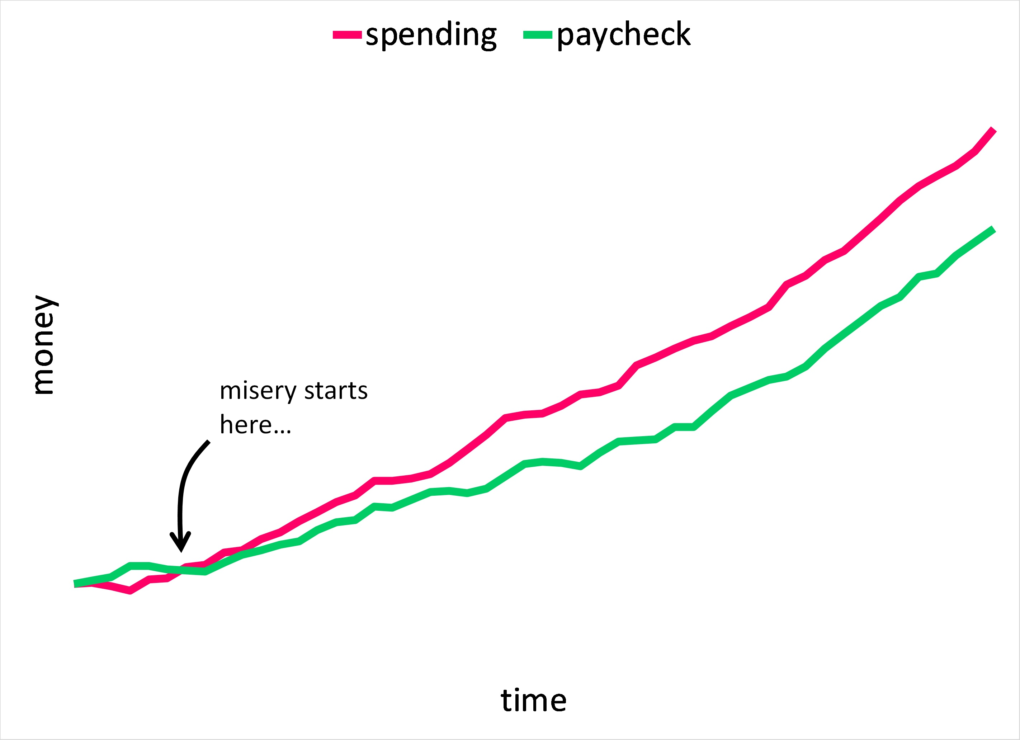

Last, it is easy to inflate our standard of living in line with our incomes but cutting back on the good life when the time comes is not going to be as easy.

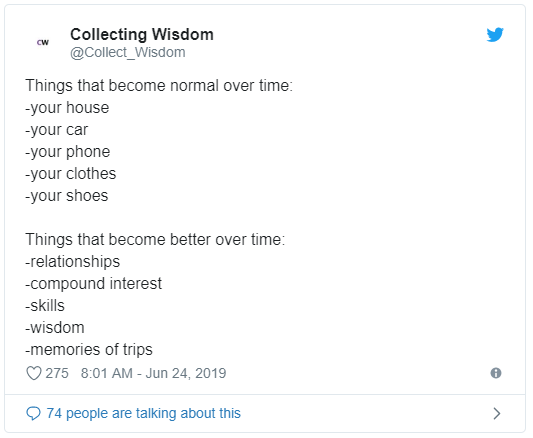

And we think that the next pay raise or that hot new car or a sprawling home will make us happy but then we hedonically adapt to all that stuff. So, as we make more money, our desires and expectations rise along with it, and we are back to where we were on the happiness scale.

I say design in occasional splurges but a life of permanent affluence, even if you could afford it, is no fun.

To the Vanderbilts again, not all was lost of that great fortune as a tiny piece of it funded the inception of Vanderbilt University. Then there is the Grand Central Station in New York. And last, we got CNN’s Anderson Cooper, son of Gloria Vanderbilt and a direct descendant of the Commodore.

As a parting note, here is Cooper on the prospect of inheriting her mother’s $200 million fortune that she built all on her own…

His branch of the Vanderbilt dynasty no longer considers inherited money anything but a “curse” that drags kids down and wastes adult lives.

Thank you for your time.

Cover image credit – Wendelin Jacober, Pexels