Rule number one – don’t lose money. Rule number two – never forget rule number one. That of course is classic Buffett.

So, say you have a choice to invest between the shares of the hottest tech stock around or in a basket of shares that represent say the entire tech sector. Which one do you think is a lower risk option? A basket of tech stocks of course.

Prices moving up and down, even violently at times, is not risk. The likelihood of capital loss whenever realized is the true risk. The fortunes of a single company can decline and likely never recover but the fortunes of an entire sector, never.

Or they could.

Say you invest in a fund that owns a basket of oil company stocks and you think that is safe because you are technically diversified across many businesses, albeit in a narrow sector. Can you estimate that sector’s cash flows say a few decades from now?

Not easy to do, right. Because it is possible that the entire sector could be disrupted out of existence or at the very least, prominence due to advances in technology.

So, there is a non-zero probability of capital loss by investing for the long-term in a supposedly diversified investment.

But what about investing in all sectors of an economy through an investment that represents say 500 of the largest publicly traded businesses in these United States? That is the S&P 500 index that we are all familiar with.

So, we are now getting to a point where we have diversified away any diversifiable risk associated with a single company or a sector in a given economy.

But then there are still gaps as S&P 500 is a collection of 500 LARGE publicly traded businesses in ONE country. Then there are mid-size companies, small companies, international and emerging market companies. And then there are domestic bonds, international bonds, real estate and so on.

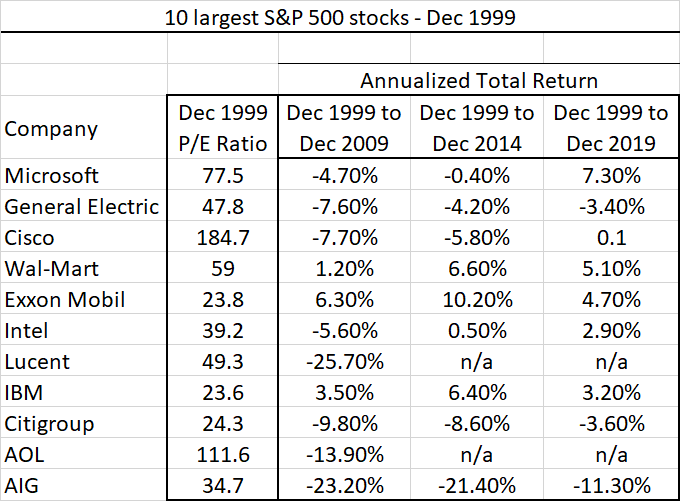

Oh, and talk about S&P 500, you remember the Dot-com boom of the late 1990s, don’t you? The S&P 500 then, just like these days1, was as top-heavy (top ten holdings occupying 30 percent of the value in that index) and as concentrated as it can get.

What is the problem? Performance below of the top ten largest stocks in the S&P 500 index then to twenty years later.

n/a = bankrupt

So, $100 invested in Microsoft in December of 1999 became $410 dollars, 20 years later. Nothing spectacular but not as bad.

In Cisco Systems, $100 became $102 over 20 years. Stashing your cash under your mattress would have been a better deal than that.

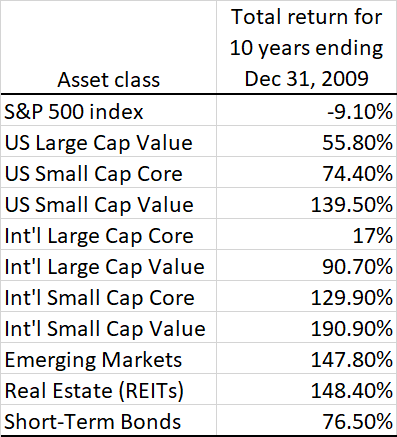

But back to S&P 500 and since that index was so concentrated back in 1999, quite naturally it took a beating when the Dot-com bubble imploded. And that showed up in that index’s subsequent 10-year performance…

So, if you just owned the S&P 500, you had a small problem. Not a big problem if you could persevere through. But many cannot.

And many cannot because to persevere through a decade long underperformance, you’d have to approach portfolio building from a much deeper perspective than most do.

But back to overconcentration in a single stock or a sector risk, you better be super lucky and choose right. Because if you chose wrong which is statistically more likely, you’d be in deep doo-doo. And that could happen even with the rest of the economy firing on all cylinders.

Overconcentration can either make you stupendously wealthy or completely demolish your plans with the latter more likely and a vivid example of how that can unfold is outlined in this Wall Street Journal story. It talks about how workers at General Electric loaded up on employer stock during their tenure to a point where many of them had pretty much their entire net worth tied up in this one stock.

Now who would have betted against General Electric, a diversified conglomerate that has been around for 126 years and counting and is the only surviving member of the original Dow Jones Industrial Average.

And who could have predicted that even the bluest of the blue chips with market leadership in products that cater to many segments of the global economy can fall on hard times? The consequences for the employee-stockholders though are not pleasant as this story of Gary Zabroski highlights…

You had a job for life if you had gotten in there,” said Mr. Zabroski, 61 years old. He rose to punch-press operator and retired in 2016, after working 40 years at the century-old plant, which roared to life during World War II and still churns out engines for jets and helicopters. He left GE with an annual pension of $85,000 and company stock valued at more than $280,000.

Retirement looked pretty good until GE shares collapsed. His shares are now worth about $110,000, prompting a late-life job hunt. “I never planned on retiring and having to go back to work,” said Mr. Zabroski, who has monthly mortgage payments and supports a partially disabled wife. “It’s kind of scary.”

Now Mr. Zabroski’s situation isn’t nearly as dire considering his $85,000 a year pension but then that could be at risk as well if the company continues to flounder which is likely.

Among those hard hit by GE stock losses have been company retirees, including former factory workers who took advantage of a stock-ownership plan to build their savings. For decades, the company has had a program that encourages employees to buy GE shares by offering to match 50% of worker contributions, which were taken directly from paychecks.

With 71.4% of assets needed to cover its pension liabilities, GE is one of the worst funded large corporate pension plans in the U.S., according to an April report by consulting firm Milliman Inc. GE’s pension obligations, nearly $100 billion at the end of 2017, are underfunded by almost $30 billion.

Mr. Marruffo‘s situation isn’t looking that hot either as he too loaded up on his employer’s stock…

Mr. Marruffo, 71, started with GE as an apprentice, working in different engineering and manufacturing areas. Just like many business experts, he respected GE’s management. Mr. Marruffo accumulated GE stock through the company’s Savings and Security Plan. He figured the company was just about invincible, which made the fall in its stock price devastating. He sold some last year but still owns about 6,000 shares. He now regrets he didn’t sell more.

Employees need to think very carefully about investing their own money beyond 10% in company stock,” said Corey Rosen, founder of the National Center for Employee Ownership, a nonprofit that works with companies. “If you are looking at retirement, then diversification is a good thing.”

Getting folks to diversify out of their employer stock is never an easy discussion, especially when it relates to some of the hottest tech darlings around.

Plus, as an employee-stockholder, you want to believe in the future of your company so much that it is hard to bring yourself to let go of your shares.

But let go you must because the business landscape is strewn with past darlings that could do no wrong that are now just a shell of their former shelves. And some don’t even exist anymore.

Take Yahoo, for example. It had a peak market value that exceeded $100 billion at one point but eventually got sold to Verizon for a mere $5 billion a decade and a half later. Then there are stalwart businesses like Sun Microsystems, AOL, JDS Uniphase, Palm and many others from the Dot-com days that have since vanished.

So, do you sell all at once? Because once you do, you know what is going to happen the day after you sell. The stock is going to shoot up like a rocket.

Instead, I say you slowly scale out over time just like how you scaled in. Pick a date and a timeframe and sell and keep selling until you are out.

Carl Richards in his book The Behavior Gap talks about a conversation you should be having with yourself if you have a majority of your net worth tied up in a single stock or a sector.

A guy I know had his money invested in his company’s stock. He had enough money to retire comfortably, but he believed there was a good chance the value of the stock could continue to rise – maybe even double. He wanted to know if he should sell the stock upon retirement, or hang on and wait for the stock to go up further.

We had the Overconfidence Conversation.

I asked him three questions and we answered them together.

Question one: What happens if you hold the stock and you’re right – the stock doubles?

Answer: You’ll have more money.

Question two: What if you hold the stock and you’re wrong?

Answer: You’re going back to work – maybe for twenty years.

Question three: Have you been wrong before?

Answer: Yes.

He sold the stock.

And if you can still handle the risk and the implications to your quality of life if things don’t turn out as planned, then you have your answer as well.

The real big risk we should be worried about is the risk of outliving our money, especially considering that most of us in our 30s and 40s and even 50s could be around well into our nineties. That is 30 to 40 years of drawing income from our portfolios so if the job of saving the right amount in the right investments in the right accounts and tweaking as we age is not done right, our quality of life in the later years will likely suck.

And we don’t want that outcome for any. You could get a second shot at making it if you happen to be the next Colonel Sanders but for most of us, there is just one.

That is not to say that you should not take risks but take risks that are statistically more likely to pan out. Overconcentrating in your employer stock or any stock for that matter though, is not one of them.

You have one shot at this, don’t screw it up.

Thank you for your patience and time.

Cover image credit – Sander van der Wel, Flickr

1 December 31, 2019